What World War I Trench Art Tells Us About Its Creators

Ann Hood on Commemorating the Fallen and Unknown Soldiers of the Great War

I cannot remember how I came to become so fascinated by World War I. Growing up in the 1960s, I was surrounded by World War II veterans—the neighbor who lost his arm at Iwo Jima, an uncle who stormed the beach in Normandy, the fathers of friends whose medals were hidden in drawers and closets.

Maybe it was my relentless desire to be different that drew my attention to that long ago war that was so overshadowed by the more recent ones and the one in Vietnam that played out on our televisions every night. Or in seventh grade when I read Dalton Trumbo’s Johnny Got His Gun, an anti-war novel about a soldier whose injuries have taken everything from him except the ability to think and remember. Or a year or two later when I watched All Quiet on the Western Front on the Late, Late Show. But somehow the Great War captured my imagination and never let go.

I felt like those long dead men were reaching out from those miserable trenches to speak to us today.I knew by heart the story of the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand and his wife Sophie by Gavrilo Princip in Sarajevo in June of 1914, which led to the start of World War I. I knew that over a million soldiers were killed in just five months in the Battle of the Somme and that by the time the war ended over nine million had died. “Trees,” the first poem I ever memorized, was written by Joyce Kilmer, who died in the war, as did the British poets Rupert Brooke and Wilfred Owen. Siegfried Sassoon and JRR Tolkien survived, but the war haunted them and their writing for the rest of their lives.

In 2014, I even traveled to London to see the 888,246 ceramic poppies—one for each British military fatality in WWI—placed around the Tower of London to commemorate the War’s 100th anniversary. And I passed on this fascination to my son Sam, who embraced it with all the fervor I had and then some.

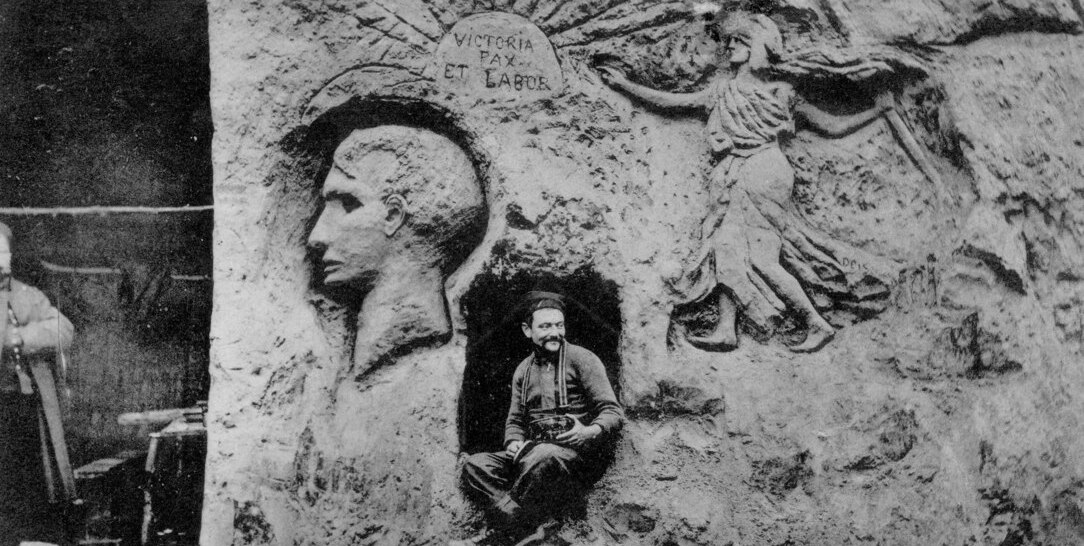

About ten years ago, Sam called me, excited. He told me to look at the Instagram account of someone named Jeff Gusky. There I found dozens of black and white images that appeared to be taken underground. “Are these in caves?” I asked Sam, squinting at photographs of carvings and drawings of people and symbols. “Not caves,” Sam said. “Trenches. World War I trenches in France.” I looked closer, not quite believing what I was seeing.

Here a carving of a man and boy. Here a heart, a sexy woman, a soldier praying. I felt like those long dead men were reaching out from those miserable trenches to speak to us today. Jeff Gusky, the ER doctor and photographer who was photographing trench art across France for National Geographic Magazine, said in his artist’s statement: “The battlefield of WWI was utterly inhospitable to life…The artwork they left behind are messages to the future and vivid reminders that our humanity is our salvation….”

On the underground walls of trenches all over France, soldiers awaiting the arrival of German troops, drew sketches of the girls they left behind, national and religious symbols, and even relief sculptures. This trench art shows us a different view of World War I and connects us to these soldiers, many of whom did not survive. It’s very likely that some of these drawings represent the last acts of the nameless soldiers who created them.

This trench art shows us a different view of World War I and connects us to these soldiers, many of whom did not survive.Just as the war itself captured my imagination, so did this art hidden underground in farms and fields across France. Who was the young man who so painstakingly drew that woman on the wall of his trench? How lonely and frightened was he? Did he survive the battle? The war? I wrote to Jeff Gusky and asked if I could come to France and see the trench art myself. But the trenches are off-limits to visitors to protect them from possible vandalism and to preserve them. If I couldn’t literally see them, then, as a writer, I would have to see them in my imagination.

That is how Nick Burns, the protagonist of my new novel The Stolen Child, was born. I invented a college boy from New England who is scared and homesick in a trench on a farm in France in 1917. To pass the time and to comfort himself, he draws a Fourth of July picnic in his hometown with everyone he loves—parents, neighbors, girlfriend, even his dog—on the wall. When Camille, the farm wife and an artist herself, sees his drawing she dismisses it as amateurish and challenges him. “You never had to work hard. You never had to make a hard decision, did you?” she asks Nick. A week later, when the Germans finally arrive, Camille forces Nick to make the hardest decision of his life, a decision that haunts him. Sixty years later, at the end of his life, he returns to France with Jenny, a college dropout he hired to accompany him to unravel the consequences of what he decided on that day in 1917.

This Memorial Day, Siegfried Sassoon’s words ring out to me: “Have you forgotten yet? Look down, and swear by the slain of the War that you’ll never forget.” When we metaphorically look down beneath the fields of France, those soldiers look back at us through the art they left for us to someday find. I imagine Nick’s Fourth of July picnic beside the praying soldier and father and son. “Look up,” Sassoon wrote, “and swear by the green of spring that you’ll never forget.”

__________________________________

The Stolen Child by Ann Hood is available from W.W. Norton & Company.