What Woody Allen’s Manhattan Tells Us About Society’s Relationship With Powerful Men

Erin Keane On Undoing Self-Made Cinematic and Family Myths

Of all the lies I once believed about my mother and father, the biggest was the one I told myself. For most of my life, I reveled in my origin story as a daughter of the grittier, downtown version of Woody Allen’s Manhattan, a movie I loved fiercely, perhaps because it too demanded a certain amount of self-deception.

In 1972, my mother was fifteen years old—a beautiful runaway from a respected military family, living as an adult under a fake name in New York’s East Village—when she met my father at Googie’s, her favorite bar. They fell in love and married that year. He was a recovering heroin addict, sporadically employed and with a criminal past, a self-taught, bullshitting Renaissance man who drove a cab and wooed her with barstool poems. He was also the same age as her father.

Googie’s is where I thought my family’s story started, when he was thirty-six and nobody knew—or more likely, nobody cared—that my mother was a child, claiming to be in her twenties with a name and a backstory that had nothing to do with being the daughter of an Army officer and a mother in bespoke beaded dresses who saw cotillion and college in her daughter’s future, not hitchhiking across the country, sleeping in subway stations, hanging around bars with penniless actors and artists, drinking for cheap.

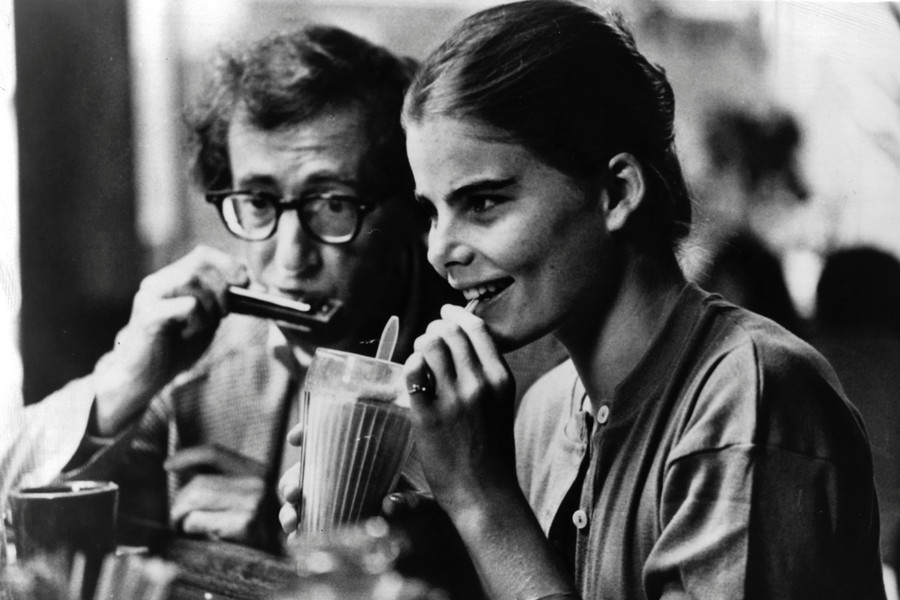

After all, in Manhattan, we don’t see what seventeen-year-old Tracy was doing before she starts dating Isaac, the twice-divorced protagonist who is her father’s age and who cracks self-conscious jokes about it in front of his friends. We’re not actually supposed to care. A girl becomes visible to the world, stories like Manhattan taught me, when a man appears next to her in the frame.

Their choices were formed by a culture that romanticizes men who have big appetites that shape their allure and cause their downfall.

It is embarrassing now to admit how much I believed in Manhattan and for how long it remained one of my favorite films. And yet I know I’m not alone. A movie doesn’t become a perennial best-of without a certain cultural consensus behind it. (See the 2007 critical outcry from New York magazine after the “doddering” American Film Institute dropped Manhattan from their Best 100 Films list. The magazine protested that the movie is “an absolutely perfect film, one of the few that, a hundred, two hundred years from now, they’ll still be watching, list or not.” Call me impressionable, but 2007 was the year I started my own career as a culture writer, and I gave a lot of weight to what New York’s critics wrote.) That same consensus has long positioned men’s narratives as the world’s de facto serious stories, even when the fictions they contained were wildly self-indulgent.

After Allen’s adopted daughter Dylan refused to stay silent as an adult about her allegations that he molested her when she was a child, the cultural consensus now about Woody Allen is, to quote actor Wallace Shawn’s defense of him, that he is a “pariah.” As a supporter of survivors of abuse and exploitation, I have no appetite for his work anymore. But I can’t pretend I never did. If you had asked me ten years ago if I thought there was anything wrong with the relationship Allen wrote for his stand-in Isaac and the teenaged Tracy, a role that garnered Mariel Hemingway an Academy Award nomination, I would have waved away the question with a noncommittal shrug. To make great art, we must create space and empathy for characters who make bad choices, right? And that grace we extend to fiction has long bled over to include the art’s makers and their misdeeds.

At long last, that’s beginning to change. Prominent men in numerous industries have been exposed, denounced, and diminished over their exploitations of power, including with teenage girls. Headlines treat those men as powerful outliers. But I don’t believe they’re special. Their choices were formed by a culture that romanticizes men who have big appetites that shape their allure and cause their downfall, all while casting aside the unruly girls left in their wake as damaged goods.

I am also of that culture, a product shaped by it. My father, the complicated seeker; my mother, his beautiful life raft. I never questioned their marriage’s power imbalance, how it tilted everything in his favor. He died when I was five, which transformed him into a romantic figure in absentia—a fantasy, a celebrity of sorts, intimately knowable and shrouded in mystery all at once. My mother outlived him, moved on from his death, and built a new life for herself and us. But I remained loyal to him in the most childlike way, nurturing the hole his absence left in me, tending its jagged borders as a memorial to his tragic ruin. Flawed male protagonists and their dissolute creators, self-destructing musicians with sordid reputations—I welcomed them into that space. I craved their voices because I couldn’t hear his.

*

On their first date, my father took my mother to a seafood restaurant on Sixth Avenue in Greenwich Village that I think must have been the original Captain’s Table. Red, as he was called because of his ginger hair and beard, was tall, barrel chested, and blue eyed. As he steered her toward their table, he leaned over to murmur in her ear, “Mafioso hang out here.” My mother believed him. He had a way of saying things that made them sound true. She had wide green eyes, high cheekbones, fair skin, and long dark hair that hung straight down the middle of her back. She could two-finger whistle a cab down from a block away.

That night, she was wearing her favorite dress—a halter-top maxi, midnight blue swirled with purple clouds and moons—and platform sandals that made her taller than five-nine. At this point, my father still believed she was twenty-four years old and that her name was Alexis—both lies. She had heard hints of his past too. Only some of them turned out to be true. As they ate and talked, a cop in street clothes approached their table, with its bottle of wine and two glasses, flashed his badge, and asked to see her ID.

“I left my purse at home,” she lied without hesitation.

A girl becomes visible to the world, stories like Manhattan taught me, when a man appears next to her in the frame.

The cop stared, unimpressed. Clearly, he suspected she was too young to be drinking on a date with this man who was old enough to be her parent. He must have noticed they weren’t acting like father and daughter. Maybe he was part of the NYPD’s recently formed Runaway Unit, tasked with keeping an eye out for minors who weren’t supposed to be living on their own, grilling them for identification, and arresting them if their stories didn’t line up. To a cop, she was a potential criminal. The graves of twenty-seven boys murdered by a serial killer in Houston, their disappearances initially written off as runaway cases, were still a year from being found. That discovery would lead to the Runaway Youth Act being passed in 1974, federal legislation designed to help, rather than criminalize, street kids. By then my mother had been married to Red for almost two years and my big brother was four months old. According to his birth certificate, she was nineteen when he was born. But that was a lie as well.

It all could have ended before any of that began. But my father was a practiced liar too.

“This is my wife,” he said, a bold thing to say on a first date. The cop decided not to question it. A man in authority had been given a reason by another man not to care about a girl out of place. A reason was all he needed. He left them alone, and the story continued until it ended with my father’s death, nine years and two children later.

Now, when I tell people the story of my family, their eyes round, they murmur “wow” with—what, exactly? Titillation? Maybe. Shock? Sometimes. They’re naive, I used to tell myself. Conventional families are for other people, for those parents who met in college, at church, or at the office, who drove minivans to school pick-up, those people nobody could imagine ever being young.

The first time I questioned this understanding, I was sitting on a bed in a tiny hotel room in Manhattan in 2015, writing my reaction to new revelations from Mariel Hemingway about the making of Manhattan. My family’s story, normal as it was to me, bore more than a passing resemblance to my erstwhile favorite movie, a once-celebrated auteur’s romantic comedy classic now derided as the creepy wish-casting of a man who later pursued his own partner’s college-aged daughter.

Have you ever held an obviously absurd belief for so long that once you see the truth clearly, you can only wish the ground would swallow you whole as punishment for being so pathetically oblivious?

Writing about it on the internet is the next best thing.

That morning, I was in New York on a three-day stay in a toile-decked theater district hotel close to my company’s midtown office. Inside, it felt like I had stepped from the twenty-first century back into a film from the 1970s. The hotel lobby, shabby-elegant. The room, just shabby. No coffeemaker, which I took as an act of aggression. It was my first visit to the New York office since joining the staff of Salon six months earlier as a staff writer working remotely. Most of my coworkers lived in the city, and I wanted to meet them in person.

After work the night before, I had gone out with a friend for wine and gossip and later had met my uncle for ramen. It had been a full day, and I was exhausted. As I let myself into my room, a breaking news alert popped up on my phone. Fox News had published an excerpt of Mariel Hemingway’s new memoir that included an unflattering allegation about Allen’s behavior after the filming of Manhattan: after she turned eighteen, he showed up at her home and tried to convince her to fly to Paris with him on what she finally understood was to be a lovers’ getaway. Her parents encouraged her to go, and Hemingway was left to find her own strength to turn him down, which she did.

I realized I couldn’t write about the dismantling of Allen’s gauzy fiction’s plausible deniability—its lie—without also admitting that Manhattan had once been my favorite movie.

Hemingway’s revelation came two and a half years before the Harvey Weinstein exposés blew #MeToo into prominence, but we were right in the thick of the multiple Bill Cosby sexual assault investigations as they were unfolding. I had written about my own experience interviewing Cosby—over the phone, thank god—and the misogyny I had encountered, and I had held myself accountable for not questioning him then about the allegations. I had also asked why the arts and entertainment press, myself included, had refused for so long to understand that they were also working a crime beat.

The old media practices of treating misconduct allegations without formal charges, confessions, or convictions to substantiate them as gossip were starting to crumble, and the debate over the separation of (presumably valuable) art and the (allegedly reprehensible) artist was in full swing. Hemingway’s account didn’t allege any crimes, just unprofessional behavior that could be considered creepy. But it did make the “separate the art from the artist” argument that Manhattan’s admirers had leaned on for its cinematic respectability look awfully thin. There appeared to be precious little daylight between Allen and his protagonist. First, the artist hires a young girl, who has her first kiss with him on camera while she plays the role of the adoring and adorably eroticized, then exquisitely heartbroken, girlfriend. This is the art. And then, according to Hemingway, the artist waits the bare minimum of time for propriety’s sake before trying to make his fantasy real.

I read the Hemingway excerpt in long gulps, knowing we would have to cover it. Half our readers would cheer their assumptions about Woody Allen being confirmed, and half would be incensed over the outrage being directed at one of their favorite geniuses and would defend him. As I opened my laptop to summarize the new revelations, I realized I couldn’t write about the dismantling of Allen’s gauzy fiction’s plausible deniability—its lie—without also admitting that Manhattan had once been my favorite movie.

This was almost a year after Dylan Farrow’s open letter in the New York Times detailed her damning story of being sexually abused by Allen (allegations he denies), which I had originally—as a teenager in the 1990s reading the publicist-spun, incomplete narratives of the Farrow-Allen-Previn family rift in checkout-lane magazines hundreds of miles from New York City—misconstrued as an ambiguous claim in a bitter custody battle. After Dylan’s letter, though, I could no longer see Allen’s films as I once had. And yet I couldn’t escape my own body of work, littered as it was with fond references to Manhattan, like one breezy story previewing an orchestra’s Gershwin program with as many words devoted to Allen’s use of Rhapsody in Blue in the film’s opening monologue as to the composer himself.

My brief commentary on Hemingway’s shocking yet unsurprising story, and my own blind spots regarding the film, poured out of me in less than an hour. Writing it, I had to ask myself why I had loved this film and its objectionable pairing of Isaac with Tracy for so long. It was because I loved my mother and father and had believed for my whole life in the failed redemptive promise of their doomed romance.

_____________________________________

Excerpted from Runaway: Notes on the Myths that Made Me by Erin Keane. Copyright © 2022. Available from Belt Publishing.

Erin Keane

Erin Keane is a critic, poet, essayist, and journalist. She’s the author of three collections of poetry, and editor of The Louisville Anthology (Belt Publishing). Her writing has appeared in many publications and anthologies, and in 2018, she coproduced and cohosted the limited audio series These Miracles Work: A Hold Steady Podcast. She is editor in chief at Salon, where she has worked since 2014, and teaches in the Sena Jeter Naslund-Karen Mann Graduate School of Writing at Spalding University.