What Ursula K. Le Guin Meant to Me: Four Writers Remember

How a Legendary Writer Made Lives Better

Adrian McKinty

“Le Guin raised questions in the fields of science fiction and fantasy that no one else was asking at the time.”

In the summer of 1978 after a series of dull books I finally could take it no more and I huffily demanded of the librarian “if there were any books in existence that were as good as The Hobbit?”

The place was Carrickfergus, Northern Ireland and I was 10 years old.

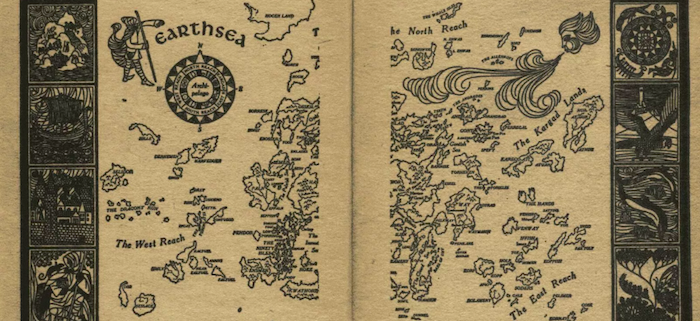

“Yes,” the librarian said, “Follow me,” and she led me to an author called Ursula Le Guin in the science fiction section. “This one,” she said and put into my hands a copy of A Wizard of Earthsea. I was skeptical. The cover had a pensive looking boy staring at the ocean in a battered paperback edition. But when I flipped the book open there was a map of an archipelago that didn’t exist anywhere in our world. “Ok,” I said and sat down on the floor and began reading.

The librarian tapped me on the shoulder, “We’re closing up now,” she said. When I looked out the window it was nighttime and about four hours had gone by.

That’s what Ursula Le Guin, who died on Monday January 22, had the power to do. She created entire worlds that readers fell into and believed in utterly. Her complex, philosophical Earthsea books for children about a young trainee wizard were the gateway drug to her even more psychologically astute and ethically complex science fiction.

Le Guin raised questions in the fields of science fiction and fantasy that no one else was asking at the time. Questions about sexuality, gender, the morality of war and peace. She knew that science fiction was a genre about ideas but a genre dominated by white men in their forties and fifties needed fresher ideas to keep it interesting. Le Guin’s ideas came out of left field. She didn’t talk about it much (and it wasn’t mentioned in her New York Times obituary) but she went to the same high school and grew up in the same milieu as Philip K Dick. For Dick and Le Guin their big original ideas had to be backed up by consistent internal logic and intellectual rigor. If a planet has three genders instead of two how would that affect society? If a man’s wishes were always come true what nightmares would that induce? Could a society based on anarcho-syndicalism actually exist and if it could what would it look like? Should a species that doesn’t value its ecosystem even deserve to survive?

Le Guin came from an academic family and she didn’t suffer fools gladly (she wasn’t impressed by anyone in the Trump administration) but she was also an incredibly generous book blurber, encourager of young talent and teacher. I never met her in real life but my wife Leah took a short story class with her once and Leah remembers a mentor who saw patience and kindness as the highest virtues.

Back in the summer of 1978 I walked into a library in Carrickfergus and skeptically asked a librarian if anyone had ever written a book as good as A Wizard of Earthsea.

“You liked it then?” the librarian said.

“Very much,” I told her.

“You should write to the author and tell her. Authors like to hear that sometimes and who knows she might even write back.”

It was the first time I’d ever written to an author and two months later an envelope came back with a Portland, Oregon postmark on it. Le Guin had taken the trouble to answer all my questions about Sparrowhawk, “the rule of names” and how exactly the magic worked on Earthsea.

Winner of the Hugo Award, Nebula Award, Locus Award, World Fantasy Award, in 2014 Le Guin was awarded the National Book Foundation Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters. She was the last of the giants of the golden age of science fiction and her wit, intelligence, kindness and originality will be sorely missed.

Adrian McKinty’s is the author of the Sean Duffy mystery series.

![]()

Gabrielle Bellot

“She won’t ever really die. Great writers never really do…”

Some writers seem like they won’t ever die, like they’ll keep smiling and cracking quips forever. For me, Ursula Le Guin was one of those, like Gabriel Garcia Márquez, James Baldwin, Derek Walcott. All became sick, weak, towards their ends, yet I imagined they would, somehow, always be there.

Le Guin taught me so much. Yet the lesson I remember best, the one she returned to so often, was about the power of naming.

In “She Unnames Them,” Eve reverses biblical legend: she removes the names from animals, rendering all creatures on the planet one unified mass. Le Guin’s Eve is wise and erudite, living at once in the primeval Garden of lore and knowing of T.S. Eliot, Darwin, and Dean Swift, as inside-outside time as Garcia Márquez’s Macondo. Yet for all the fruits of her knowledge, she is startled by what happens when she finally gets all the animals—even the dogs and garrulous parrots who loved their names—to accept namelessness. “They seemed far closer than when their names had stood between myself and them like a clear barrier,” Eve muses, wistful and somewhat surprised by the effect of her decision, “so close that my fear of them and their fear of me became one same fear.” Names, she realizes, divide; namelessness unites, yet it is a vast, almost transcendent unity, wonderful and sublime in one breath, terrifying the next. “And,” she continues,

the attraction that many of us felt, the desire to feel or rub or caress one another’s scales or skin or feathers or fur, taste one another’s blood or flesh, keep one another warm—that attraction was now all one with the fear, and the hunter could not be told from the hunted, nor the eater from the food.

Here, Le Guin does what she did so well. She transforms the world by naming (or unnaming), then showing, something that may initially seem small, like the child in Omelas who is tortured so that everyone else can be perfectly happy, or the gender and sexual fluidity of an alien race in The Left Hand of Darkness, or how time and dreams become fluid, morphing reality in The Lathe of Heaven.

And the idea of namelessness, its awesome and awful power, alongside the potential fluidity of gender, filled other stories by her, like “A Trip to the Head,” in which Le Guin’s protagonist, “blank,” has no fixed identity or memory; he has lost his “real name,” he says early to a seemingly imaginary being besides him, evoking the imagery of Hayao Miyazaki’s later masterpiece, Spirited Away, in which the witch Yubaba takes ownership of her servants’ names, until they forget them entirely. Later, blank’s companion, who has become a woman named Amanda, suggests that blank try being Amanda, and that it matters, too, what race they are: “What if Amanda was black?”

Here, Like Margaret Atwood in “Happy Endings,” or like her own “Omelas,” which gives readers the power to imagine the setting any way they wish, Le Guin is dissecting storytelling itself: her characters can fluidly become whatever they need to, yet their identities in the world matter. Like Octavia Butler, one of the few other prominent female sci-fi writers of her generation (and one of even fewer black women in the genre), Le Guin understood that who we are in our bodies in the world changes how the world perceives us.

Nuance mattered to her. In that vein, I loved her refusal to be pigeonholed. She was always simply herself, laughing away at interviewers who asked her what Omelas—Salem, Oregon seen from a sign backwards—really meant. She brushed aside the way “Great American novel” is so often conceived as some singular, masculine pursuit. And she refused to let the genres she was often described as working in be pigeonholed, either. She took sloppy definitions of science-fiction to task in a conversation in 2010 with Atwood in which, rightly, she argued that much of what we deem sci-fi is just fantasy with a veneer of advanced technology or science. “There have been really few science fiction movies,” she told Atwood. “They have mostly been fantasies, with spaceships.” (Fantasy, she proffered, could never happen; true sci-fi, however, showed something possible.) Her work evokes much to me—Philip K. Dick, Moebius, Atwood, Lord Dunsany, the kaleidoscopic anime dream-film Paprika, amongst many others—but is ultimately, as all good writers must be, distinct.

I love sci-fi, yet the genre has a deeply misogynistic, myopic history. As Justine Larbalestier reveals in the appositely titled The Battle of the Sexes in Science Fiction, much early American sci-fi featured women as crude tropes, if women existed in it at all; authors like Isaac Asimov sneeringly argued in letters in fan magazines of the genre that women had no place in sci-fi because it would make such stories into sloppy romances. (Because, of course, women can only be the objects of heterosexual romantic conquest.) James Tiptree Jr., with more secrecy than George Eliot, wrote under a male name to help herself get published; a few writers, speculating about her identity before its revelation, mused that Tiptree couldn’t be a woman because of how she wrote. In a well-known speech from 1972, “The Android and the Human,” Dick infamously declared—both jokingly and seriously—that “a time may come when, if a man tries to rape a sewing machine, the sewing machine will have him arrested and testify perhaps even a little hysterically against him in court.” Dick, who was expanding upon an idea of Stanislaw Lem that a “time may come when for example a man may have to be restrained from attempting to rape a sewing machine,” uses the old sexist trope of women being “hysterical” and transforms women being raped into a boys-club joke worthy of the President’s locker-room talk. “Let us hope,” Dick says to bring the vile image to its conclusion and adding a bit of bizarre homophobia to the mix, “that it is a female sewing machine he fastens his intentions on. And one over the age of seventeen—hopefully a very old treadle-operated Singer, although possibly regrettably past menopause.”

Le Guin, like Butler, like Laureline in Valerian and Laureline, gave the middle finger to all this and named it what it was: bullshit. She didn’t dismiss the genre for its pervasive bigotries; instead, she sought to reform the system from the inside.

This, too, is why I loved her: like the ones who choose to walk away from Omelas after seeing the cruel system on which their home is built, she helped make the world—our world, and the ones swirling invisibly-visibly inside us—better.

I’ve changed my mind. She won’t ever really die. Great writers never really do, no matter what their tombstones and the flowers, real and ghost, at their graves argue.

Gabrielle Bellot is a staff writer at this website and contributes regularly to the Atlantic, The Cut and the New Yorker.

![]()

Jon Michaud

“In art, ‘good enough’ is not good enough.”

I first read that stern, brutally truthful sentence in the spring of 1984, in a high-school library in the suburbs of Washington DC. It’s from The Language of the Night, Ursula K. Le Guin’s 1979 book of essays about reading and writing science fiction and fantasy. For some reason, the book wasn’t allowed to circulate, so I hid it in the stacks to ensure it would be there for me every day at lunchtime. Why was I in the library reading instead of eating in the cafeteria with my friends? Simple: I didn’t have any friends—at least none who felt as important to me at 16 years of age as this 55-year-old feminist science-fiction writer who lived on the other side of the country. For the two weeks it took me to read The Language of the Night, (and for the many return visits I made to re-read parts of it), Le Guin was my preferred lunch date and my closest confidant. She’s been a touchstone for me ever since.

I’d been introduced to her work the year before by my father, who preferred the harder science fiction of Arthur C. Clarke and Isaac Asimov. He passed his copy of The Left Hand of Darkness on to me. I still have it—the 1981 British paperback edition published by Orbit. We came to be in possession of the British edition because we were living in Northern Ireland at the time, where my father was stationed as an envoy—similar to Genly Ai, the narrator of Le Guin’s masterpiece. Indeed, Genly Ai’s experience on Gethen was not unlike mine in Northern Ireland. In that strange, bellicose place, I, like Ai, “longed for anonymity, for sameness. I craved to be like everybody else.” Eventually, like Ai, I came to love my new home and I came to have my heart broken by its history and its people.

Imagine Genly Ai returning to Earth after his experiences on Gethen and you will have a sense of why I was in the library, reading Le Guin instead of hanging out in the cafeteria. Living in Belfast had changed me. I no longer belonged in my native land. The condition of not belonging is, of course, common among those of us who feel the impulse to write. I’d composed a derivative fantasy novel that year, but I had much larger ambitions as a reader and as a writer. The Language of the Night gave me an idea of what I was getting myself into. The book was a missive from the life I wanted and it pulled no punches. “Art, like sex, cannot be carried on indefinitely solo,” Le Guin warned. “After all, they have the same mutual enemy, sterility.” Yikes. But she also gave me hope. In “Why Are Americans Afraid of Dragons?,” she wrote, “I believe that maturity is not an outgrowing, but a growing up: that an adult is not a dead child, but a child who survived.” Her death is a great loss, but the world remains full of children who survived into adulthood in part because of her art.

Jon Michaud is the author of When Tito Loved Clara.

![]()

Maria Dahvana Headley

“Le Guin is the person who turned me into a teenage radical.”

My first encounter with Ursula K. Le Guin took place in a classroom in rural Idaho. The Left Hand of Darkness was mysteriously squashed into a shelf in the back of the room, despite the community being the kind that would not normally allow anything so potentially Satan-esque into its midst. If I am honest, I was lured by the book because I myself am left-handed, and because I had an inflated yearning to shape myself something epically Ungood. Darkness? Fine. I was thirteen. I was pretty sure I was about to learn how to be a witch or a thief. I didn’t… or maybe I did.

The book started to yank me into becoming a writer, because I had not actually known there was such a thing as justice before. I had not thought about oppression, about bureaucracy, about even, gender. Thirteen is about the right moment to start thinking about those things, and to start noticing the levels of injustice all around oneself. I had an assignment to write a 500-word story. I sat down, in a fury of rebellion against everything, even assignments, and wrote a novel in my notebook. In it, a man, innocent of any crime, and never informed of the charges brought against him, spends an entire Mead legal pad tunneling out of prison. When he finally reaches the light, inexplicably, (I had four pages left) he is in something that is basically Sherwood Forest. I don’t know what to tell you about that. I had seen a trailer for Robin Hood, Prince of Thieves, and it bent me into a fever of arrows and errors. I wrapped the whole thing up with a pile of sentences involving maids and Marions and my prisoner being revealed to not be a man at all, but a woman warrior, and very good with a sword, damn it.

Things progressed from there. I read more Le Guin, and muttered more. Le Guin is the person who turned me into a teenage radical, and from there into the adult radical I ended up becoming. Her words about her work, the way she spoke about herself without apologizing, made me try harder, and reach higher. I made myself into a witch, or a thief, or a writer. She’s still hitting me hard.

My next novel comes out in July (by next, I don’t mean to imply there was a 27-year gap between legal pads—there’ve been a bunch of other books too, but this one is particularly inspired by Le Guin). I wrote it in part because I read an interview with Le Guin about ambition, and she was very clear that it was necessary to have it, and majorly. Okay, I thought. Fuck it. I’ll adapt Beowulf. She’s the one who made me feel that I was allowed to go after the big things as a writer, whether novels in notebooks, or shouts about gender justice, equality, and capitalist structure. This one’s about police violence, racial injustice, colonialist “gentrification,” a dragon, and yes, a woman with a sword.