For one week only (January 6 to 12), Film Forum presents James Baldwin Abroad: A Program of Three Films. Get up to two discounted $11 tickets (regular $15) to the screening and first two weeks of showings by entering promo code LITHUB at checkout. Subscribe to Lit Hub’s weekly newsletter What to Watch for more literary film and TV content.

*

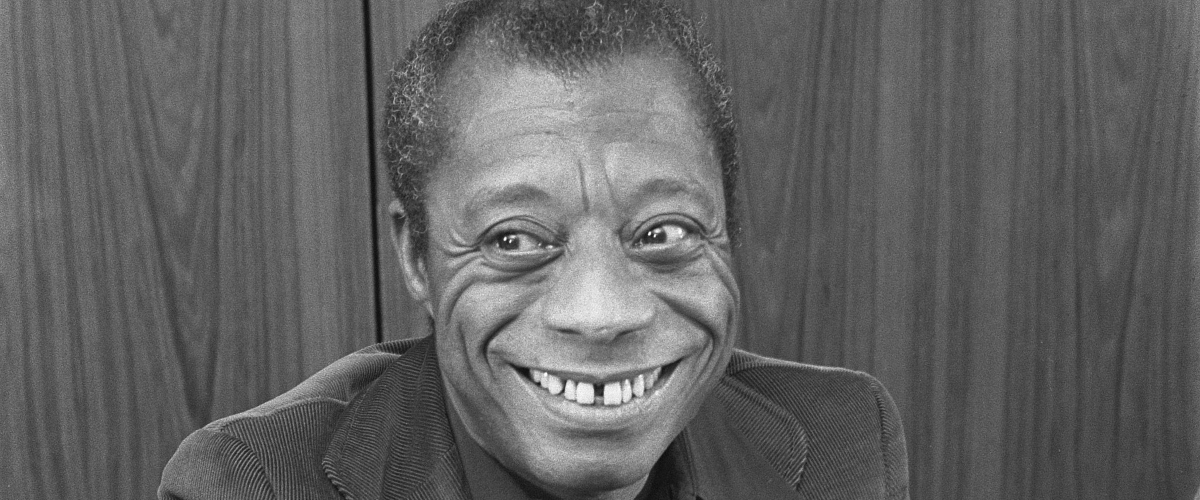

James Baldwin: the brilliant thinker, writer, and activist whose prescient essays, plays, and novels continue to shine a searing light on American racism 35 years after his death. Born in 1924, in Harlem, Baldwin spent much of his life abroad, and in these three short films—made in Istanbul, Paris, and London (with Dick Gregory)—he can be charming, candid, churlish, witty, and acerbic. Whether ruminating on his own “American-ness,” his experience as a child-minister, Black Power, or the nature of love and sexuality, creativity, freedom, and survival—his unsparing opinions are never less than eye-opening, and his onscreen presence never less than riveting.

*

James Baldwin Might Have Been Most at Home in Istanbul

When asked why he came to Istanbul, Baldwin alluded to the city being a location of healing for him, presented it as a place in between things, both Asian and European; a city where he could, for a while at least, slip off the various identities assigned to him by others and try to exist in between things too; try to become a human being, was how he put it. In Istanbul, he said, he could begin again.

Baldwin’s Turkish decade coincided with the middle of his career not just chronologically, but thematically; years that led to significant artistic growth and exploration. It was while in Istanbul that Baldwin would write his most American works, including Another Country, The Fire Next Time, and No Name in the Street. He would tell friends Turkey had “saved” his life. He would talk about buying a place in Istanbul, settling permanently.

When he eventually moved out of Cezzar’s apartment, Baldwin rented a place of his own: a red house overlooking the Bosphorus that once belonged to a Pasha. Baldwin embedded himself in the neighborhood, becoming a regular at the Divan Hotel bar, befriending local activists and intellectuals, staging productions for community theater. His direction of Fortune and Men’s Eyes, a play on gay men in prison that looked at their sexual lives, opened up new possibilities for Turkish theater, which typically had little room for overt explorations of sexuality. (Keep reading)

*

James Baldwin in Paris: On the Virtuosic Shame of Giovanni’s Room

He abandoned his religious beliefs around the same time he was attempting to come to terms with his sexuality. Soon, New York itself was too much for him to bear, and he decided to leave; perhaps an ocean away, he would find a clearer compass of the self. But, of course, it was a journey inward, as well, a spelunking into a cavernous dark. He did not specially choose France; as he remarked on the Dick Cavett show in 1968, “I didn’t care where I went. I might have gone to Hong Kong, I might have gone to Timbuktu. I ended up in Paris… on the theory that nothing worse could happen to me there than had already happened to me [in America].”

In France, he discovered a new world. There was racism and homophobia, but they felt lighter, less overwhelming, than in America. It seemed less extraordinary and subversive for black and white people to walk together, even hold hands or more, in public. He soon latched onto a bisexual white Swiss artist, Lucien Happersburger, who helped solidify Baldwin’s realization that he was attracted to other men. Happersburger was 17 and his skin was far lighter than Baldwin’s, but that didn’t matter; in this world, Baldwin could ease up, somewhat, and seek out love. “In Paris, I didn’t feel socially attacked, but relaxed, and that allowed me to be loved,” he reflected.

Brimming with a new energy, Baldwin began to write the books that would become his first novels, including Giovanni’s Room, and he forged a lifelong relationship with France itself, which would become his home for decades to come. He had entered the cavern—and, to his surprise, it was large and well-lit, warm with the glow of candles and lamps. The cavern was allure itself, dark and stark from the outside, comfortable and cozy within, at least for a bit. And to enter that maw was more than just to accept his queerness. It was to reject the narrowness of his father’s dreams, the claustrophobia of his childhood. He still grappled with layers of shame, yet even that was a little more bearable there. (Keep reading)

*

The Last Days of James Baldwin’s House in the South of France

As we wandered through the house and the grounds for over an hour, I found myself surprised by how emotionally fraught the confrontation between my past and present experiences of that space proved to be. I felt both sadness and anger that the house was let go by the Baldwin family following David Baldwin’s death, even though it was possible to hold on to it. I also felt frustration and despair about my own impotence to do anything, blaming myself for not having taken many more photographs in 2000 (who knew the house would be lost so soon?!), regretting that I never saw the writer’s study furnished and inhabited. I kept circling around the structure, photographing frantically, getting annoyed as my son nagged me to leave. So much needed to be done, preserved, and documented; so much had been lost already. The obvious reason behind all this turmoil was the painful fact that the only viable writer’s house for James Baldwin anywhere in the world was crumbling away before my eyes. It was not yet gone and could possibly be saved, but it was effectively out of reach of anybody who might want to preserve it by the sky-high price that real estate bidding wars had stamped on it.

Who could afford to pay 30 million euros for a writer’s house that was falling apart? Would it be bulldozed to provide space for shiny new tourist quarters or a rich man’s villa and swimming pool? Or would it be left alone, the lesser of two evils, waiting for the ravenous landscape to absorb the crumbling structure completely? (Keep reading)