What the Social Lives of Koalas Tell Us About Ourselves

Danielle Clode on Solitude and Companionship in the Animal Kingdom

As I follow Ash around the different enclosures at Cleland, I notice that the animals are not evenly dispersed. More often than not, two koalas will be sitting together—nearby, side by side or “spooning,” with one hugging the other’s back, sometimes resting or even sleeping on each other. It happens too much for it to be chance, and it doesn’t seem to be related to the proximity of their food.

“Are those two related?” I ask Ash, looking at a huddle of grey fur, with two faces turned to watch us.

“No, I doubt it,” she says. “Monica and Riley are rescue animals. They came in at different times. They just really like hanging out together. Sometimes Deputy joins in their group hugs, but mostly he keeps his distance.”

We move on to another enclosure.

“These two are interesting,” Ash says. “Cleo and Vicki were brought in together from Kangaroo Island after the bushfires and were very attached to each other. And they’ve stayed really close. At some point earlier in their lives they’d been tagged, and their tags are sequential numbers, so I guess they must have been caught together then as well. I reckon they’ve always stuck close together.”

I’m surprised by this unexpectedly social behavior in an animal that is known for being solitary. I’d always thought that koalas were fairly aggressive to each other.

“That’s only in the breeding season. The males are pretty stroppy then,” says Ash. “The females can get pretty agitated then too and it’s dangerous for the joeys—they sometimes get knocked off.”

Why is it, then, that from time to time koalas seek out the company of creatures not of their own kind?

I ask Kath Handasyde about her observations of wild koalas. In the sometimes-overcrowded remnants of the Victorian forests, you might expect mothers to move their young on more forcefully.

“They do. Once the young ones get to about 2 or 3 kilos, the mothers will give them a bit of a box to stop them hanging around too much,” she says. “If they’ve got another little one coming on, they can’t afford to be carrying around a great big joey any more.”

“I think it’s hormonal,” Kath continues. “We had one female who was given a contraceptive when she still had a joey on her back. That boy just got bigger and bigger and she never pushed him off. She was only 6 kilos and he was 4 kilos! They have an amazingly strong maternal instinct. Wild adult females without a joey will sometimes come to the ground and pick up a small baby koala squeaking in distress.”

I wonder about this kind of incipient sociality. Plenty of animals are downright antisocial—hostile, pugnacious, murderous to their own kind, even when resources are not in short supply. It’s hardwired into their nature. Common wombats are notorious for being cute, cuddly and affectionate as infants, but downright lethal as adults.

“When they start to mature and hit puberty,” one wildlife officer said about wombats, “they just hate everybody and everything.”

Koalas, though, appear to be flexible about their sociability—happy to share their space, and even enjoying each other’s company, when resources are abundant, but more than willing to go it alone when food is in short supply and it’s each koala for themselves. Southern koalas are said to be more sociable than northern koalas, but even here they live contentedly enough in high densities in captivity. Food quality seems to be the key to their apparently solitary natures. Such behavioral plasticity has successfully adapted them to significant environmental uncertainty. Perhaps it is another reason they have coped so well during the fluctuating climate and forests of the last few million years.

*

We’re inclined to judge koalas harshly for their apparent lack of sociability, as if being happy with your own company is a shortcoming. Humans are extreme outliers on the scale of primate and even mammalian sociability. We are obligingly social creatures, living in vast, complex, multi-level aggregations that are rivaled in their intricacies and spread only by insects. We are so determinedly social that we even adopt nonhumans into our social networks or invest inanimate objects with human characteristics. We see the world through a brain wired for sociality and interactions with others. As a result, we struggle to understand or accept others, human or animal, whose sociality does not conform to our own.

We define animals as presocial, subsocial or sometimes parasocial—as if there is some kind of evolutionary hierarchy from primitive solitary creatures to highly evolved, complex social systems like our own. But solitary is not the opposite of social; it’s the opposite of gregarious. Sociability is a spectrum, not a binary condition, and many species that are usually regarded as solitary—like red foxes or feral cats or badgers—sometimes form communities and exhibit amicable social interactions.

Perhaps we are just oblivious to interactions that are different from our own, or occur outside our limited range of perceptions—such as the constantly refreshing network of chemical signals that lace the landscape, or long-distance auditory communication. The world of blue whales and humpbacks is shaped by long-distance communication over many miles of ocean. The world of many terrestrial mammals is a complex web of chemical signals, mapping the age, activity and interests of individuals who share their ranges. Are you really alone if you are in constant communication with someone else?

We’re inclined to judge koalas harshly for their apparent lack of sociability, as if being happy with your own company is a shortcoming.

There are costs and benefits to sociality. Individuals in social groups might gain more reliable access to mates, shared parenting of offspring, better food-gathering strategies, collaborative shelter building or defense and protection against predators. But living in groups also comes at a price—it intensifies competition for food and shelter, attracts predators and significantly increases disease transmission and interspecies aggression. To put it simply, in many species, competition for food drives individuals apart, while sex brings them together—at least for a short while.

Koalas don’t show any obvious signs of social bonding, like grooming each other, but I’m not sure that they are particularly solitary either. When they do meet others (koalas, humans or other animals) they greet them with gentle nose bumps. Other than during the breeding season, they show less aggression towards each other than cats or dogs do on first meeting. Koalas are clearly a naturally dispersed species, probably because of food supply.

But if you mapped their activity over a certain area, I wonder if you would find they are more or less likely to interact with one another than they would by pure chance? A bit of both, I suspect, depending on the individual, which is itself an interesting reflection on personal associations—what we might term friendships.

Everything about koalas tells us that food is a limiting factor. Despite the vast coverage of eucalypt forests, finding enough of the right food, the best food, the least-toxic and most-nutritious food—sufficient not only to survive but to breed and raise young to adulthood—is a constant struggle. Small wonder they typically spread themselves as out across the forests, maximizing their chances of success in an erratic and unpredictable climate. But this does not mean they are unsociable. Given an abundance of food (and without the fired-up hormones of the breeding season), they seem entirely amicable creatures for whom the touch and smell and warmth of their own kind is as comforting as it is for us.

*

There is no reason for koalas to associate with animals that are not koalas. Aside from the microbial symbionts that all animals are in constant contact with, I can’t think of any benefit a koala would gain from cross-species interactions. They can’t offer koalas any protection from predation, or any food or shelter. For the most part, other animals can only present a risk to koalas. So why is it, then, that from time to time koalas seek out the company of creatures not of their own kind?

Solitary is not the opposite of social; it’s the opposite of gregarious.

A friend who raises horses noticed some of her young fillies carefully and cautiously investigating something in a tree in a corner of the paddock. They stretched their noses out towards the low foliage, sniffing, ears forward.

My friend walked around the paddock to see what they were looking at. Young fillies are not always the most sensible of creatures. They bolt and startle at the slightest disturbance, sometimes tangling themselves in fences. She stood ready to intervene and calm them down. Something moved in the vegetation, and she noticed a koala climbing down the tree. It stopped at head height to the horses and slowly turned around, looking at them.

The more adventurous of the fillies stretched out her neck, and the koala reached out towards her face. Its long claws lengthened against the soft, delicate skin of the filly’s cheek. My friend held her breath. The filly snorted in surprise, huffing horsey breath on the koala, but the koala did not move. The filly leant back in, and the koala seemed to stroke her face before turning back to the tree, and both animals went their separate ways.

We rarely witness such interactions in the wild. It’s hard enough to see koalas on their own, let alone with other animals, undisturbed by our presence.

__________________________________

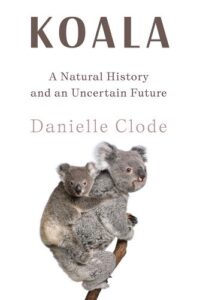

Excerpted from Koala: A Natural History and an Uncertain Future by Danielle Clode. Copyright © 2023. First American Edition 2023. First published in Australia in 2022 as Koala: A Life in Trees by Black Inc., an imprint of Schwartz Books Pty Ltd. Used with permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.

Danielle Clode

Danielle Clode is a biologist and award-winning author. Her books include Killers in Eden, Voyages to the South Seas, and The Wasp and the Orchid, which was shortlisted for Australia’s National Biography Award. She lives in the Adelaide Hills, South Australia. https://danielleclode.com.au