What the Rest of America Can Learn from California’s Turnaround

Demographic Shifts Might Save Us Yet

For conservatives, California is often thought of as a cautionary tale, what can happen if you have too much diversity, too many hot tubs, and too many voters leaning in on the liberal end of the political spectrum. But if you play the tale all the way out—from its midcentury success to the decline suffered at the end of the last century to the resurgence stirring now—it may be not as much a warning as a sign of hope that the current national craziness will end—although not without inflicting substantial pain along the way. After all, the national spasms resulting from demographic change, rising inequality, and political polarization may be causing headaches and mood swings now, but the view from the other side of the cycle is not all that bad: California’s economy is on the mend (although more for some than for others), discourse is surprisingly civil, and there are still too many hot tubs. Recognizing that immigrants settle in, that economic shocks sort out, that environmental action does not sink jobs, and that raising taxes on the wealthy does not stunt growth is key to assuaging national anxieties about the challenges ahead.

Major California cities and regions.

Major California cities and regions.

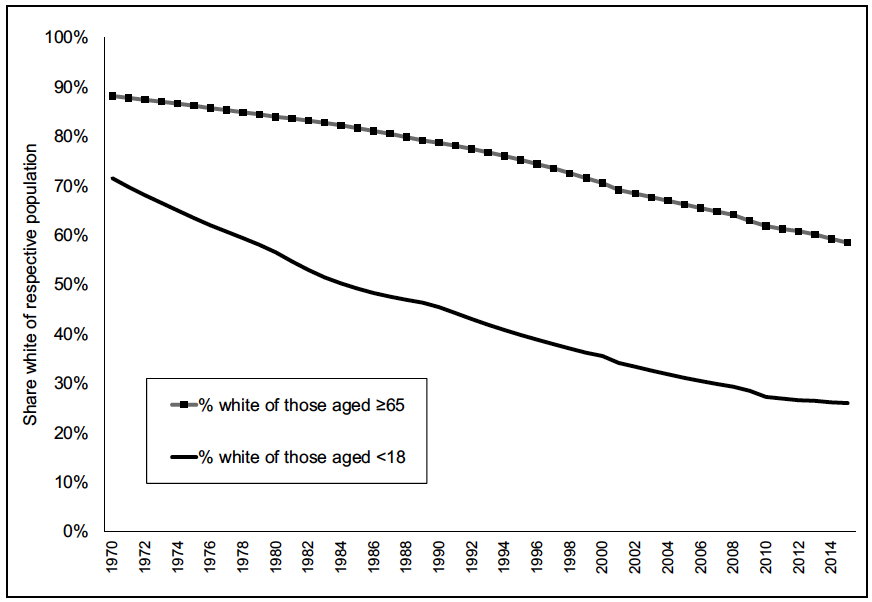

This is particularly important because one of the key factors behind California’s stabilization is likely to take time for the nation: the slowed pace of demographic change. In California, the share of foreign born is on the decline, and the state’s largest metro area—Los Angeles—is the only large US metro that did not see an increase in Hispanic children between 2000 and 2010. Perhaps most significant has been the shift in what might be termed a “racial generation gap”—the difference between an older population that is mostly white and a youth population that is mostly kids of color. Such a gap can be both measured and tracked over time: the figure below charts this by showing the percentage of seniors who are white and the percentage of youths who are white between the years 1970 and 2015. Note that the widening difference between the two lines—the racial generation gap—occurred in the years of California’s maximal political turmoil (from 1970 to the mid-1990s). Since then, the gap has stabilized and has begun to decline—and with that has come a diminishment in racialized state politics as well.

Racial generation gap in California, 1970–2015.

Racial generation gap in California, 1970–2015.

Why is it important to think about the age chasm? Research suggests that the racial generation gap can lead to social distance between generations—with the old not seeing themselves in the young—that then lowers voter willingness to consider public investments, including in public education. That certainly seems to fit the California pattern—both the long period of disinvestment sparked by Prop 13 and now the sudden turn to thinking we may just be in it all together. But simply hoping that disgruntled white voters will just naturally age out or wise up is not exactly a fix. Instead, we must be honest about and address the generational disconnect in order to create bridges to a new social contract. And we need to do that quickly: California’s decades of conflict need not be half a century of slow-paced agony for the rest of the country. A dash of rules change, a bit of attitude change, and a clear commitment to common ground can help others avoid wasted energy spent on ultimately futile political conflicts.

Of course, to get there, we have to understand what is really behind California’s comeback. One popular account focuses on the return of Democrat Jerry Brown, a former governor who presided over the beginnings of the decline and is now presiding over the beginnings of the renaissance. The emphasis on a key individual feeds into a common and tempting American misperception: that a singular hero can symbolize and actually explain the drama. It is true that Brown brought a certain fiscal probity as well as a fierce commitment to addressing climate change; moreover, his shift from spacey to sage, from saboteur to savior, makes for a neat redemption story. But such a tale is incomplete and misleading, not only because it leaves out the broader forces that drive history but also because it ignores the multiple actors who have also played their roles, especially those associated with California’s sophisticated social movements.

What were these broader forces? Demography played a role—a higher share of people of color helped to tilt the state left—but demography was not necessarily destiny. As Roger Kim, former executive director of the Asian Pacific Environmental Network, notes, “Yes, demographic change can work in our favor but you have to do the hard work of investing in the infrastructure to make it so. . . California doesn’t look like this by chance; there was an incredible amount of work that went in.” Actually mobilizing that population required campaigns to naturalize immigrants threatened by California’s anti-immigrant mood swing as well as broader efforts to develop new leadership and generate enthusiasm among infrequent voters who might be upset about the racialized attacks on affirmative action, the dramatic increase in incarceration, and the widening divides by income.

The economy played a role as well. Deindustrialization helped to create a large mass of the working poor, but this actually triggered public sympathies and facilitated city and county campaigns for a “living wage.” The shift from older industries to high tech gave rise to business leaders generally more liberal in their leanings, more open in their attitudes, and more likely to see a role for government in, say, addressing climate change or promoting green industries. Emerging research helped to facilitate a growing civic consensus that high levels of inequality were actually corrosive to economic stability as well as democratic governance. And the combination of demographic, economic, and political trends produced support for a more concerted effort to address the state’s opportunity gaps: in 2013, California passed something called the Local Control Funding Formula, an effort to ensure that more educational resources flowed to the poorest children in the state’s public school systems, and in 2016, California was also among the first states to adopt a plan to raise its minimum wage to $15 an hour.

California is also beginning to reinvest in 21st-century infrastructure, including efforts to connect the state via high-speed rail, to shepherd in an era of mass transit in urban Los Angeles, and to rework the state’s busy ports to reduce their impact on climate and air pollution. California’s larger cities, once the arenas of economic distress and civil unrest, are staging a comeback as a new “creative class” seeks to agglomerate near urban amenities; in a sort of “be careful what you wish for” moment, city planners and advocates for low-income residents who once worried about disinvestment and neighborhood decline now find themselves struggling against the displacement caused by gentrification.

Shifts in the political rules of the game have been essential as well. In 2008, the drawing of electoral districts for state and national offices was removed from the hands of the legislature and is now done by a citizen commission; in 2010, the state’s budgeting rules were changed so that an expenditure plan can pass with a simple majority rather than a two-thirds supermajority, a rule that gave small blocks of conservative legislators maximum leverage; and in 2012, the regulations governing term limits for state officeholders were changed such that California’s legislative leaders are not constantly thinking of their next electoral move and have more capacity and time to strategize and govern.

“Policy change does not always start in the halls of state or local legislatures but rather in the streets, workplaces, and voting booths, where power is contested.”

All these demographic, economic, and political trends help explain the turnaround, but another key part of the California comeback—one left aside by most writers and analysts—has been the role of social movements in shifting the underlying political calculus. As noted earlier, organizers did not assume that demography itself would bring change; movement builders were intentional about amplifying the voice of the new majority. The state has become a hotbed of movements for decent wages, immigrant rights, racial equity, and environmental justice. So rather than what we saw in DC through the administration of Barack Obama—in which a moderately progressive president found himself unable to accomplish his agenda as the grassroots excitement of his presidential campaign fizzled and the red-hot heat of Tea Party activism shifted the dynamic—change in California was propelled by a buzzing band of organizers who pushed for a more inclusive and more sustainable state.

Indeed, the state’s ability to achieve fiscal balance with new taxes on the wealthy was actually an idea prompted by movement activists who dragged the political establishment left—and utilized a new form of “integrated voter engagement” that combined community organizing with voter mobilization to flex the political muscle that made it happen. A more pro-immigrant set of state policies evolved partly because of concerted lobbying by immigrant rights activists, with their victory partly symbolized when Kevin de León, a former organizer who cut his teeth protesting Proposition 187, became president pro tem of the senate. And recent successes in pushing state ballot propositions to reduce sentences and shrink the prison population were secured by advocates who had the guts to ask voters for support in a nonpresidential election, believing (rightly) that they could motivate new and occasional voters to the polls—that is, craft a younger and more minority electorate—even without the usual presidential lure at the top of the ticket.

Omitting movements from the picture—and focusing just on a septuagenarian governor or even the economic and political rules of the game—will leave you with a story that is one step short. Policy change does not always start in the halls of state or local legislatures but rather in the streets, workplaces, and voting booths, where power is contested. Movements are not everything—the shifting preferences of the business class and ways in which politicians respond to changing incentives are also key. But understanding the strategic choices of California’s organizers is critical to understanding the evolution of the state and can also help others in the United States understand the need for and nature of grassroots work in an era of reaction. In short, while Americans are normally tempted to think that what matters is the right person—that Obama could magically save us from our own divisions or that Trump alone can make the difference between decline and recovery—it is really the right collective capacities and alliances that are needed to drive change and make it stick.

Understanding the need for continued mobilization and policy change is also key to future progress in the Golden State. Californians are a bit like the person who finds sobriety after a long period of addiction: amends are important but just a starting point to undoing all the damage caused along the way. Saying you are sorry that you starved the state in order to lower taxes does not restore the education that was denied a generation. Feeling sheepish about ignoring racial disparity and banning affirmative action does not address the frightening gaps in college completion for Latinos and African Americans. Being shamefaced about excessive sentencing, over-incarceration, and rampant prison construction has little impact unless you now choose to exhibit a commitment to effective reentry programs. And expressing embarrassment about our over-reliance on autos is more convincing if you also double down on efforts to address greenhouse gas emissions.

The state will therefore need to both lead the nation and heal itself. Politicians and corporate leaders will need to speak with and work with labor organizers addressing inadequate pay and a shrinking middle class, environmental advocates pressing to hold the line on air quality, and undocumented immigrants who cannot vote but who nonetheless can and do lobby elected officials. It is in the rebalancing of forces that a new and more sustainable state can be crafted—and this will be important for America not only because California can model what the nation can become but also because it may wind up being one of the last lines of defense for the majority of Americans who did not vote for a President Trump.

Addressing the federal government’s abandonment of leadership in confronting climate change, Governor Brown vowed in December 2016 that “if Trump turns off the satellites, California will launch its own damn satellite.” Meanwhile, many of the state’s high-tech coders, engineers, and executives have vowed to not contribute to the building of a Muslim registry or to any efforts that could lead to mass deportation. And while the pro-“law and order” speechifying of Donald Trump has led many in the Black community to worry about the unleashing of state violence in their neighborhoods, California cities continue to try to make progress on improving relationships between communities and police.

So California is in a state of resistance—but the task ahead will be not just to defend but also to develop and deploy. The state can illustrate what the nation could gain if it drops the anti-immigrant sentiment, confronts the reality of climate change, and works together to address income inequality; because of this, the Golden State needs to get it right. California will also need to spread the message in ways both symbolic and concrete, including working to export good policy today as much as it exported bad policy in the past, and sharing some of the evolving models of integrated voter engagement that have better aligned movements and politicians.

__________________________________

From State of Resistance: What California’s Dizzying Descent and Remarkable Resurgence Mean for America’s Future. Used with permission of The New Press. Copyright © 2018 by Manuel Pastor.