What Statistics Cannot Say: On the Uncounted Dead

Mary L. Dudziak on Resisting the Brutality of State Numbers

My last sight of my brother may have been in a fundraising video. A man with longish gray hair lay face down on the walkway of a park in Southern California. The wheelchair behind him was like the kind my brother would have had. It was draped with a green sweatshirt and a bag of belongings. A medical worker knelt down and spoke to him about a motorized wheelchair, which he was hoping for. “He has refused help,” the narrator said to the camera.

The film was otherwise filled with earnest medical workers providing care to people who lived outdoors. That head of hair on the ground looked like the one I remember from the time my brother turned up in a Nevada hospital after decades of silence. I cut his hair and beard with little fingernail scissors—the only implement at hand.

Some months after the video was filmed, my brother spent the last day of his life on a street in Southern California. Through his six decades of sobriety and addiction, he always loved to be outside. Several weeks after his passing, the coroner’s report is not yet filed. Without a cause of death, it is impossible to know what column of figures to put my brother in.

Death is personal, but it is also a matter of state. This begins with the body itself, for the state takes possession of the body when a cause of death is unknown. The coroner’s office does its work and then “releases” the body to a funeral home designated by next of kin. At that point, privacy cannot fully envelop the dead, for they live on in public life as data. A cause of death assigns the dead to various categories that enable the state to draw conclusions: the death rate, the leading causes, and the quantity of death over time.

It is unclear whether my brother has become a statistic of a regular death or whether he belongs in a perilous curve upward on a COVID-19 graph, showing the latest pandemic surge. During the pandemic, the dead have gained significance for the broader public as we are daily confronted with numbers of new entries on COVID mortality tables. In essence, the dead reenter society through their categorization.

Even as we lay them to rest, our practices serve the needs of the living.

Appearing as a statistic of a great threat, however, the COVID dead themselves cannot reassure their public. They cannot say: “I now exist as ashes and cannot harm you.” Instead they are required to serve as a specter, a threat. They are like Dickens’s Ghost of Christmas Future—a silent, shrouded, and terrifying figure, a reminder that death is not only inevitable. It can be cloaked with regret.

When deaths are represented in numbers on charts, the path of the disease becomes the story. The historian Jacqueline Wernimont writes of the seventeenth-century plague that numbers are thought to show something bigger, “a view of the whole.” When aggregated, however, the dead lose their individuality and are “rendered meaningless to the state in their own moment.”

Counting deaths enables the public and the state to ascribe their own meanings to them. In war, for example, the enemy’s deaths are usually thought to be an accomplishment. Nonenemy deaths by the United States require explaining. The bodies of children were found after a drone strike during the US withdrawal from Afghanistan in 2021. Their age kept them out of the category of enemy combatant—a presumptively lawful target—so that instead they might be “collateral damage,” which is what we now call civilian casualties in war. An investigation soon revealed that the entire strike was a mistake, so that all of the dead, adults and children, reinforced a narrative that the withdrawal was brutally chaotic.

Categories matter, for death can drive politics, public policy, and philanthropy. Mass casualty events—hurricanes, fires, school shootings—are often thought to require a response. Numbers alone do not give rise to concerted action, however. The nature of response is informed by the way the deaths are understood. For example, the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001, killed 2,977 people (just under the number of COVID-19 deaths in the US per day in December 2020). September 11 was not one moment but an era that that continued to spiral into darkness. Aircrafts crashing into buildings followed by toxic clouds of debris sweeping through lower Manhattan after the Twin Towers fell was just the beginning.

Long after, the nightly news would show the illuminated New York crash site, with rescue workers first looking for survivors and then searching for bodies that could not be found. Having been turned into dust, the 9/11 dead had no agency in how they were remembered. A contested set of narratives congealed into a national message, as President George W. Bush grabbed a bullhorn at Ground Zero and enlisted the dead in a war on terror. American planes were soon bombing Afghanistan. It may seem, to us, unfair that the dead were drafted into war without their consent. The dead are often called into service, however, for the purpose of war, peace, or the passing desires of those left behind. Joining the ranks of the dead makes one eligible for this kind of involuntary labor.

Their memory is invoked to goad the living into action, even, in the case of war, for the expansion of the ranks of the dead themselves. That we call upon the memory of the dead for our most important objectives is just one example of the cultural work the dead do for the living. The very way societies treat dead bodies, the historian Thomas Laqueur has shown, does not arise from the needs of the dead themselves. Instead, even as we lay them to rest, our practices serve the needs of the living.

For most of us, life in the twenty-first century United States is enabled by practices it would be unbearable for us to fully understand.

In 2020, the Black Lives Matter movement issued a powerful call to action in the names of Black people killed in senseless police violence—in 2020 alone, this list includes George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, Rayshard Brooks, and Daniel Prude. Videos revealed, for example, the callousness of Derek Chauvin, his hand nonchalantly in his pocket as he spent nine minutes asphyxiating George Floyd by kneeling on his neck on a Minneapolis street.

The BLM movement kept Floyd’s killing in the public eye, and protests erupted around the world. The sight of Floyd’s face on the pavement, the sound of his voice—“I can’t breathe”—made his humanity and individuality inescapable, even as he came to represent a history of similar lost lives. Statistics alone could not have this power, for they subsume humanity into an anonymous whole. It was these named deaths that generated mass politics, although the ultimate outcome of the political moment is yet to play out.

Contrast this with the absence of an effective call to action in the memory of COVID dead. For example, there was no mass movement to protest the Trump administration’s failure to immediately expand the production of personal protective equipment. Instead of marches demanding lifesaving, there were angry protests against mask-wearing. Embracing the rhetoric of “liberty” to demand an end to safety measures was a strange perversion of the idea of a right to die. Meanwhile, Donald Trump’s effort to dismiss the pandemic led to an absence of public memorialization. The dead were potentially toxic to his political image.

As the nation retreated behind closed doors, daily life during the pandemic was enabled by shielding the sight of the dead and of brutal conditions in hospitals, to protect privacy. Meanwhile, burials of unclaimed dead at Hart Island, New York, increased fivefold. Simple pine caskets were neatly stacked on top of one another. When a journalist used a drone to photograph the site, believing that others should know of it, he was arrested for the obscure crime of using an aircraft outside of an airport, and his drone was confiscated. This inability to see the carnage was not unlike the way terrible World War II casualty photographs were censored, in part to avoid generating an antiwar movement.

To be shielded from suffering was a privilege of those like me who could stay home. Others could not. “Essential workers” in health care and other life-sustaining industries, like food production, were on the front lines. In April and May 2020, COVID-19 surged through poultry and meatpacking plants in the United States. Meatpacking workers often labor indoors, side-by-side, in crowded conditions.

Farmworkers were also vulnerable—three times more likely than others in Montgomery County, California, to get the virus in the spring of 2020. “I think the average American has no concept of how food reaches our table,” Dr. Max Cuevas, CEO of Clinica de Salud del Valle de Salinas, told Frontline producers. “We don’t know how meat is processed. We have no idea where lettuce comes from. We have no idea how it’s harvested.” Those sheltering in place could not understand “how those people work, and how much they have to work to make a living.

American culture became a version of the workings of a slaughterhouse. Brutal actions produce dead animals that are neatly packed for American supermarket shelves. The operations of the slaughterhouse are hidden from view. They would be too shocking for meat eaters to see. That very shock, political scientist Timothy Pachirat writes, is “predicated on the operations that remove from sight, without actually eliminating, equally shocking practices required to sustain the orbit of their everyday lives.”

For most of us, life in the twenty-first century United States is enabled by practices it would be unbearable for us to fully understand. Perhaps a lesson that the rest of the country could draw from the Black Lives Matter movement, and the sight of George Floyd dying on the ground, is that there is power in seeing and showing what carnage actually looks like. Mamie Till taught the nation this lesson long ago when she revealed the battered face of her fourteen-year-old son Emmett, who had been lynched by two white supremacists in Money, Mississippi, in 1955. She opened his casket for viewing, leading Jet magazine to place his disfigured corpse on their cover, shocking the nation. It is uncomfortable to view such deaths, but preference for comfort fuels ignorance and complacency.

Whatever category my brother belonged to, he died in public, but was not seen, at least by nearly all passersby. A bus driver who had noticed him regularly did see him that day. When the driver looked again, he saw that my brother had not moved. He stepped out of the bus, and walked over to him, and he could see that life had left my brother’s body.

I like to think that this kind person’s eyes were the last to rest on my brother, and that his spirit—if there is such a thing—left at that moment to find its place in the ocean, or among the redwoods. As time passes and the coroner’s report remains unfiled, I like to think that my brother is confounding the categorizers. He is refusing to render himself into a tidy statistic. His final power was to deny the state a complete numerical accounting. He even defied the fundraisers, who have removed the video from their website after a complaint. The only way to see him was to have been there, on the street. And to stop, and look.

__________________________________

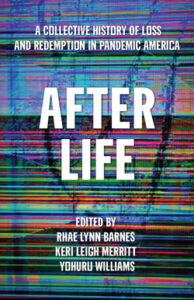

Excerpted from After Life: A Collective History of Loss and Redemption in Pandemic America, edited by Rhae Lynn Barnes, Keri Leigh Merritt, and Yohuru Williams.

Mary L. Dudziak

Mary L. Dudziak is the Asa Griggs Candler Professor of Law at Emory University. Her books include War Time: An Idea, Its History, Its Consequences (Oxford University Press, 2012), Exporting American Dreams: Thurgood Marshall’s African Journey (Oxford University Press, 2008), Cold War Civil Rights: Race and the Image of American Democracy (Princeton University Press, 2000), and edited collections, including Making the Forever War: Marilyn Young on the Culture and Politics of American Militarism, with Mark Bradley (University of Massachusetts Press, forthcoming 2021). She is past-President of the Society for Historians of American Foreign Relations, and an Honorary Fellow of the American Society for Legal History. Her J.D. and Ph.D. are from Yale University.