What Romance Writing Shares With Sports Journalism

Jamie Harrow on the Similarities Between Chronicling Hard-Won Victories in Love and Athletics

When I was younger, I thought I was going to become a sports reporter. I read all the good journalism I could find, wrote a column for my college paper, interned at Sports Illustrated. Life took me in a different direction, and when I finally returned to writing ten years later, I wrote something else entirely: a romantic comedy. But my sportswriting education was more important than I knew. What better way is there to learn how to tell a story where the ending is a foregone conclusion—a final score or a guaranteed happily ever after—than by learning how to tell a story where the result is spoiled in the headline?

A romance novel is a love story with an emotionally satisfying, optimistic ending. The reader knows the love interests will end up together. Similarly, in sports media, the reader often knows the final score before they read about it, and they can access the highlights with a few taps on their phones. But just like the juiciest sports journalism doesn’t exist merely to answer the question, “who won the game?” a romance novel doesn’t exist to answer the question, “do they end up together?” It exists to answer other questions: How do they end up together? What does it feel like? Why should I care?

As a sportswriter-turned-romance-author, I’m all too familiar with how it feels to write about something that many people don’t take seriously.

Of course, questions like these apply to all kinds of writing, whether or not the reader knows the ending in advance. But this is about how I learned.

When we write about a sporting event, we want our story to be so compelling that knowing how it ends is not enough. We want to convince the reader, essentially from the outset, that they must live the story as if they were there. Take Bob Considine’s iconic 1938 piece for the International News Service, “Louis Knocks Out Schmeling.” First, note the title. Um, spoiler alert. Here’s the opener:

Listen to this, buddy, for it comes from a guy whose palms are still wet, whose throat is still dry, and whose jaw is still agape from the utter shock of watching Joe Louis knock out Max Schmeling.

He grabs you by the shoulders and shakes you. You know the ending, but you want the details. Writing romance isn’t all that different. A walloping start helps. So does careful consideration of what is going to compel a reader to come along for the ride.

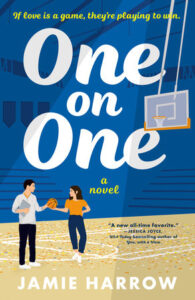

Stakes are a big one, of course. It’s helpful if they hinge on something other than which team is going to win and what happens if the love interests don’t end up together, given what the reader already knows. In my debut novel, One on One, I explore stakes that are partly distinct from the romantic relationship (the narrator’s fragile career and its chances of being smashed if the basketball team fails to win a championship) and partly in conflict with it (the risky emotional reckoning the characters will have to do with their fraught past if they pursue a relationship).

Voice, too, is crucial. When someone can read a thousand other articles or check the final score and move on in three seconds, you need to answer the question, “Why should I listen to you?” pretty quickly. You could Google the results of the 1972 World Chess Championship. Or, you could read 17,000 words on it by Brad Darrach and enjoy gems like, “[Bobby Fischer] wears a business suit about as naturally as a python wears a necktie.”

When I was a budding journalist, I struggled with imposter syndrome early on. I’m sure it was partly because I was a woman writing a sports column. I compensated by imbuing my writing voice with confidence I didn’t quite feel, inventing a self-assured voice that, in turn, made me a more self-assured writer. I faked it ‘til I made it, and it worked.

That’s probably why I spend so much time thinking about voice in romance. It’s also incredibly useful. Voice can take ordinary things, things the reader expects to happen, and make the experience of reading about them special. As a reader, I may already know where a story is going, but if I’m deep in a character’s unique point of view, the journey there is going to be full of surprises. Plus, first-person narrative is common in romance, which makes voice even more important and connects it directly to character.

The pieces of sports journalism that have stayed with me the most are more about character than the result of any particular match. Sports are a window into what it means to be human. Retired Sports Illustrated feature writer Gary Smith is one of the all-time greats precisely because of his curiosity about human nature (see: the one about the Notre Dame football coach who lost his job because he lied on his resume, or the one about the relationship between two freedivers who pushed the limits, ultimately leading to one’s death). A more recent example is Wright Thompson’s profile of Caitlin Clark. These are the kind of pieces that require months of immersion in the reporting process and leave me in awe of their depth.

Stories on these topics often tell us, or at least search for, something true about ourselves, and that is substantial.

Writing romance means focusing on a personal relationship from a close perspective, which requires a similar curiosity. The characters must feel real for the reader to buy into their romantic blunders and emotional wounds, which means the author needs to know everything about them. We spend much more time figuring out who they are off the page than we do writing them onto the page.

As a sportswriter-turned-romance-author, I’m all too familiar with how it feels to write about something that many people don’t take seriously. To make something big out of something that is, at first glance, small: a bunch of people kicking a ball around, two people falling in love. Both subjects are frequently treated as inconsequential by people who aren’t fans. But stories on these topics often tell us, or at least search for, something true about ourselves, and that is substantial. It’s why we work hard to know our characters and hold onto who they are.

So far, I’ve framed this analysis in terms of getting the reader onboard despite advance knowledge of the ending. But this knowledge can also work in the writer’s favor. In a story about a miraculous comeback, showing just how dire things got can heighten the suspense as the reader wonders how the winners-to-be are going to pull it off. Similarly, in romance, when the characters’ missteps take them further away from their happily-ever-after, the reader may become more invested in finding out how they’ll work things out, as long as it feels believable and earned in the end.

Additionally, some romance readers are only comfortable throwing themselves into an emotional story or one featuring difficult topics when they know it’s going to end well. In that respect, the happily-ever-after gives the writer the freedom and privilege to engage with those audiences in ways that would be impossible otherwise.

You will never catch me saying, “It’s not whether you win or lose. It’s how you play the game.” I’ve spent too much of my life staring at scoreboards for that. The ending matters, but only because the rest does, too.

__________________________________

One on One by Jamie Harrow is available from Dutton, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.

Jamie Harrow

Jamie Harrow grew up on the sidelines of a basketball court since her father was a longtime coach. She wrote a sports column for The Villanovan, the student paper at her basketball-obsessed college. She is a graduate of Harvard Law School and lives in New Jersey with her family.