What Robert Frost’s Philosophy of the Human Spirit Says About His Artistic Ethos

Adam Plunkett on the Poet’s Key Intellectual and Literary Influences

One of the funny things about the letters Robert Frost wrote to Sidney Cox from England between December 1912 and February 1915 is that he’s always exhorting his younger friend to be more self-reliant. Self-reliance for Frost meant independence from ways of thinking that would drown out the authority of your own spirit.

Cox’s schoolteacher fastidiousness was one such habit of mind on account of its preoccupation with rules and conventions, and Frost accordingly peppered his letters with pleas to overlook mistakes of spelling and grammar and in particular the spelling errors of Frost’s own, which he told Cox were meant for his training in the practice of ignoring them. Frost even misspelled Cox’s first name in his first letter from England: “Sydney,” not “Sidney.” Frost’s letters are full of his own ideas pronounced in bold, intriguing, and elegant terms. His observations have the force of proclamations, not least on the subject of Cox’s need to do his own thinking.

Frost was well aware of the ironies involved in his manner toward Cox. They did not make him stop. “I will scold you more in my next letter,” he promised in one letter. “I preach,” he wrote elsewhere, “but this is the last time.” It was not. Frost continued preaching self-reliance to his friend.

Frost’s formulation implies sentiment but not sentimentalism—attention to your feelings but not to the exclusion of your judgment.

The ideas animating Frost in his letters to Cox in these years, like the ideas animating his poetry at the time, amounted to an unsystematic philosophy of the human spirit. Frost’s first sustained prose on the subject, the letters go a way toward showing how his conception of spirit framed how he thought about “these things that we cant reduce to a science anyway such as literature love religion and friendship,” matters he thought the spirit couldn’t but touch on.

The letters also go a way toward clarifying how his thinking on the spirit had changed since the old faith of “Twilight”—yet they clarify only so much because they leave much of his thinking implicit. He tended to convey his views by assertion rather than argument, by statement rather than exposition. Their means of appeal was not theoretical coherence or explicitly reasoned inference but, as in poetry, direct claims on his reader’s judgment and imagination, on what his reader felt and thought. It was left to Frost’s younger friend to work out the thinking behind ideas like the following:

You do right to damn grammar: you might be excused if you damned rhetoric and in fact everything else in and out of books but the spirit, which is good because it is the only good that we can’t talk or write or even think about. No don’t damn the spirit. (ca. November 26, 1913)

I can always find something to say against anything my nature rises up against. And what my nature doesnt object to I dont try to find anything to say against. That is my rule. I never entertain arguments pro and con, or rather I do, but not on the same subject. I am not a lawyer. I may have all the arguments in favor of what I favor but it doesnt even worry me because I dont know one argument on the other side. I am not a German: a German you know may be defined as a person who doesn’t dare not to be thorough. Really arguments don’t matter. The only thing that counts is what you cant help feeling. (September 17, 1914)

Your opinions are worth listening to because you mean to put them into action—if for no other reason. But there is no other reason as important. What a man will put into effect at any cost of time money life or lives is what is sacred and what counts. (December 1914)

Literature is the next thing to religion in which as you know or believe an ounce of faith is worth all the theology ever written. Sight and insight, give us those. I like the good old English way of muddling along in these things that we cant reduce to a science anyway such as literature love religion and friendship. People make their great strides in understanding literature at most unexpected times. (January 2, 1915)

In these letters as in Frost’s other writing, he proceeds from the assumption that we are each in possession of a spirit. He makes no attempt to explain it; he denies the possibility, in fact. Its origins, its scope and limits, its commonality or variation, its physical or nonphysical nature— all of these are problems he thinks are insoluble. (Not that he didn’t wonder.) His ambition was not to explain the spirit but to live by it.

Self-reliance was for him as for Emerson reliance on that in yourself which is spirit. Insight was apprehension by means of the spirit. Poems were insights embodied in form sufficient to communicate them or else they were worthless. The spirit manifested itself in a certain kind of experience, which Frost often identified with that which you can’t help but feel. His unsystematic philosophy coheres as a guide to the attainment of that kind of experience.

Frost impressed upon Cox to respect his own judgment more, to respect others’ less, to pursue the ideas he will act on and not get stuck on excessive thoroughness or rule compliance. This self-respect and freedom from deference were important for self-reliance, Frost thought, but he did not identify self-reliance with these qualities. They were enabling conditions—whether necessary or not Frost didn’t say—but not sufficient conditions. They prepared you for spiritual insight but did not guarantee it. Nothing could guarantee it other than what you could not help but feel, which is not the same as what you merely feel strongly.

The former is not only compatible with testing your feelings with reflections but rather implies such a test as part of that despite which your feelings persist. Frost’s formulation implies sentiment but not sentimentalism—attention to your feelings but not to the exclusion of your judgment. Frost’s disavowal of weighing arguments might give the impression of disavowing careful thinking, but in light of his other writing the criticism is clearly not of the goal of careful reflection but of weighing arguments as a means to that goal. He thought that the habit had the potential to drown out the feelings of spirit and was in any case superfluous, since the arguments came to him anyway when he needed them in conversation. He also thought that the lawyerly habit gave the false impression that the problems were more susceptible to answer by reasoned argument than they actually were.

It was this general skepticism about the power of reflection to answer the questions it poses itself beyond a reasonable doubt that made the bulk of Frost’s more abstract ideas about ways the spirit might try to resolve the questions it happens to ask. Accordingly, the ideas he shared with Cox clustered around methods of obtaining spiritual experience in general and especially in the writing, reading, and teaching of literature. Frost was a prophet of self-cultivation in the form of “muddling along in these things that we cant reduce to a science anyway such as literature love religion and friendship.”

No idea animated Frost in England like what he called “the vital sentence” or, in a letter to John Bartlett, “the sound of sense.” An evocative theory of much of Frost’s own practice, the idea behind the vital sentence was that the essence of good writing was its ability to convey tones of speech that the reader could recognize in the experience of reading. The sentence could be seen not as it usually was, as “a grammatical cluster of words,” but as a sound in itself that a careful writer could affix to the page and a careful reader could hear as it was meant to be spoken.

The grammatical sentence in reading is mostly a “clue” to the vital sentence that it conveys. The vital sentence in the process of writing has to arise “in an imaginative mood” and cannot be invented at will. With vocal tones observed carefully with the writer’s “hearing ear” and affixed properly in a poem, “every word used is ‘moved’ a little or much—moved from its old place, heightened, made, made new.” In other words, the “audile imagination” allows for a clarification of meaning that is also a clarification of the spirit, something the writer could not help but feel.

Cox was borrowing Frost’s idea for an article on education, and Frost said he himself would “do a book on what it means for education” if he didn’t always wind up writing poetry instead. Frost also told Cox that Edward Thomas, a writer with whom Frost had grown deeply close over the course of 1914, “thinks he will write a book on what my new definition of the sentence means for literary criticism.”

The intricacy of Frost’s form allowed him to expand the range of experiences we have in asking questions of ourselves and perhaps of our spirits as well.

Frost as a thinker is often compared to two of his great influences, Emerson and William James. The comparisons are apt to a point. With Emerson he believed in the reliance on that in yourself which is spirit, but Emerson had a far more elaborate and mystical conception of the spirit than Frost did in maturity. Frost did believe in a supranatural aspect to spirit, but in maturity he almost always presented his ideas about it to the public in a way that required nothing other than naturalistic observation or mere common sense. He would talk to audiences about saving their integrity, for instance, if they preferred not to think in terms of saving their souls.

Where Emerson’s conception of spirit is Platonic, a transcendent essence, Frost’s is Aristotelian in a general sense, realized in the natural world and gradually apprehended by careful observation of one’s inner and outer worlds. One could always speculate about the nature of the spirit one observed, and much of Frost’s poetry is indeed the fruits of such speculation following his observations, his insight and his sight as he called them. But between observation and speculation was always a leap whose bounds Frost had painfully grown to respect.

Frost shares a picture of human decision-making with the philosopher and psychologist William James, whom Frost admired so much in his early twenties. Frost’s sense that our actions and beliefs should depend on what we can’t help but feel is similar to some of James’s formulations. Both of them stressed the vital importance of what Frost called, on James’s inspiration, believing the future in, committing to a belief in cases in which you can’t evaluate sufficient evidence to know whether to hold the belief but could benefit from acting according to it.

Yet despite these profound agreements with James, Frost was not a Jamesian pragmatist. James’s pragmatism involved a categorical skepticism of conventional notions of truth, skepticism according to which truth simply was that which it is better to believe, not, for example, what corresponds to reality. Frost expressed no categorical doubt about the nature of truth or our ability to know some truths about ourselves and the world. His skepticism was general but not categorical; it applied widely but was not a theory in itself, applied in the consideration of particulars but not in the formulation of a cohesive philosophy.

As a corrective against comparisons of Frost to Emerson and James, consider an influence on each of them to whose habits of mind Frost’s are more directly analogous: the sixteenth-century French essayist Michel de Montaigne. All of Montaigne’s essays serve to investigate one question: “Que sçay-je?” or “What do I know?” which he had written above his desk and Frost had written in French in one of his notebooks. Like Montaigne, Frost was interested in reflection unbound by subject matter and unguided by the drive to subsume his ideas under a comprehensive whole. The two were theoretical as well as observational, granular and unsystematic.

Their chief ambition and greatest rigor was in working out their own natures to determine what they thought about a given subject. Their depth and breadth of skepticism made each of them generally disinclined to think they had settled fine matters of theoretical debate and inclined to present their ideas to the public as little more than matters of preference. (They also presented themselves as far less assiduous than they were.) Their commitment to following their natures led to careful insights on a wide and heterogeneous range of subjects and also to oversights and embarrassments.

Each of them was thorough enough in his skeptical reflection on his own nature to expand the kinds of questions we ask of ourselves—Montaigne far more than Frost, to be sure. He was almost never banal, whereas Frost could be dogmatic and repetitive especially in later years. While the essay is a form of writing that can easily contain a wider range of ideas than verse—and Montaigne also invented the essay as we know it—the intricacy of Frost’s form allowed him to expand the range of experiences we have in asking questions of ourselves and perhaps of our spirits as well.

__________________________________

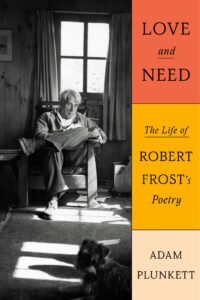

From Love and Need: The Life of Robert Frost’s Poetry by Adam Plunkett. Copyright © 2025. Available from Farrar, Straus and Giroux, an imprint of Macmillan, Inc.

Adam Plunkett

Adam Plunkett, a literary critic, has received fellowship support from organizations such as the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Leon Levy Center for Biography. Love and Need is his first book.