What Obituaries Can Tell Us About How the World Views Artists

Jim Moske Explores the Met Archives For Posthumous Stories Lost to Time

For centuries, art aficionado gossip has persisted that too much sex killed Raphael, the creative genius of the High Renaissance. His admiring biographer Giorgio Vasari can be credited with the rumor. Vasari claimed that the notoriously promiscuous painter routinely “pursued his amorous pleasures beyond all moderation” and that after one occasion in 1520 “even more immoderate than usual,” Raphael was stricken with fever. His doctor prescribed blood-letting, then a common remedial practice for all manner of ailments.

In Raphael’s case the cure proved worse than the illness. Recent research suggests the artist suffered from an underlying pulmonary disease that was likely aggravated by the administered precipitous blood loss, resulting in his death. Vasari himself suspected as much and speculated that, contrary to doctor’s orders, the unfortunate artist had been “in need rather of restoratives.”

Hagiographic images of Raphael on his deathbed have circulated widely ever since. They spread an apocryphal story that the master was surrounded in his last hours by notable peers and rivals. In a stirring nineteenth-century rendition of the scene, Johannes Riepenhausen depicted Michelangelo standing at the foot of his competitor’s deathbed, his hands clasped together and his head tilted in contemplation.

I was driven to understand its original purpose at its inception and throughout the years of its creation.

The notion that artists lived recklessly and were apt to die young as they strove for fame in a professional world crowded with ambitious, inflated egos was a recurring theme of Vasari’s great book The Lives of the Most Eminent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects (a title often shortened in English to The Lives of the Artists). This sixteenth-century bestseller established a mode of art history scholarship that thrives to this day, in which exhaustive catalogues raisonnés and copious biographical data support the portrayal of artist-subjects against richly detailed cultural backdrops.

Vasari’s sprawling text chronicles the bustling activity of hundreds of artists and inventories the many spectacular objects they made. But a more somber theme of mortality haunts the Lives. In his introduction to the first edition of 1550, Vasari voiced fear that the finest creators of his time would be forgotten and that “nothing can be foretold for them but a certain and well-nigh immediate death.” He aspired in his magnum opus “to preserve them as long as may be possible in the memory of the living,” for they “do not deserve to have their names and their works wholly left… the prey of death and of oblivion.”

Tellingly, he sequenced nearly all the profiles that comprise the book not by the artists’ birth dates but, rather, by their dates of death. When he published an expanded second edition in 1568, Vasari proclaimed with satisfaction that because of his successful book, “it can never be said that the artists had truly died, nor that their works had remained buried.” He knew that his subjects, and their achievements—and his own—would be known for centuries to come.

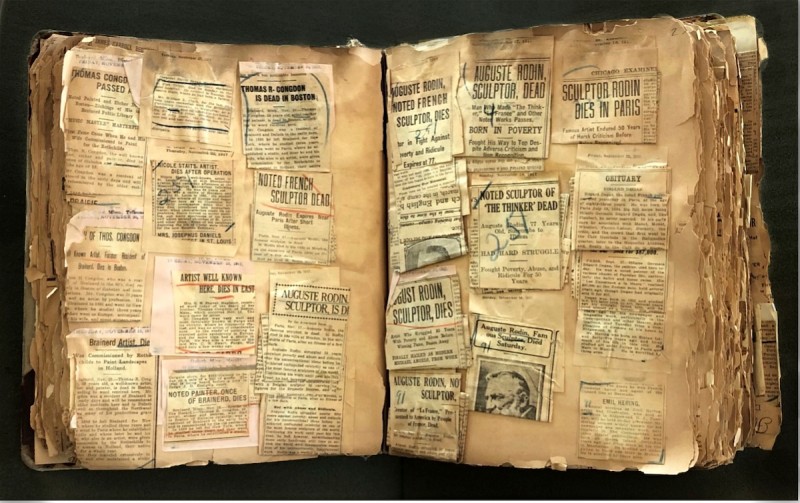

As I dug into the morbid contents of the two obituary scrapbooks I’d found in The Met’s archives, I thought of Vasari and his mission to survey comprehensively and preserve for posterity the accomplishments of all artists of his place and era. These strange volumes were packed with newspaper obituaries of painters, illustrators, sculptors, and photographers, famous and forgotten alike.

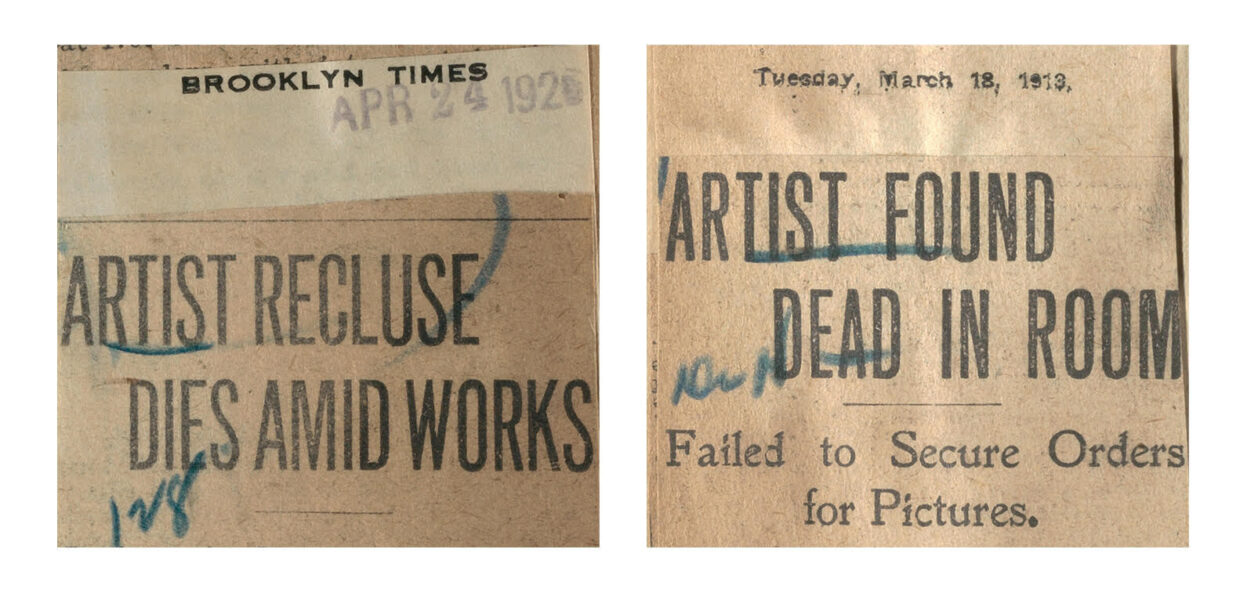

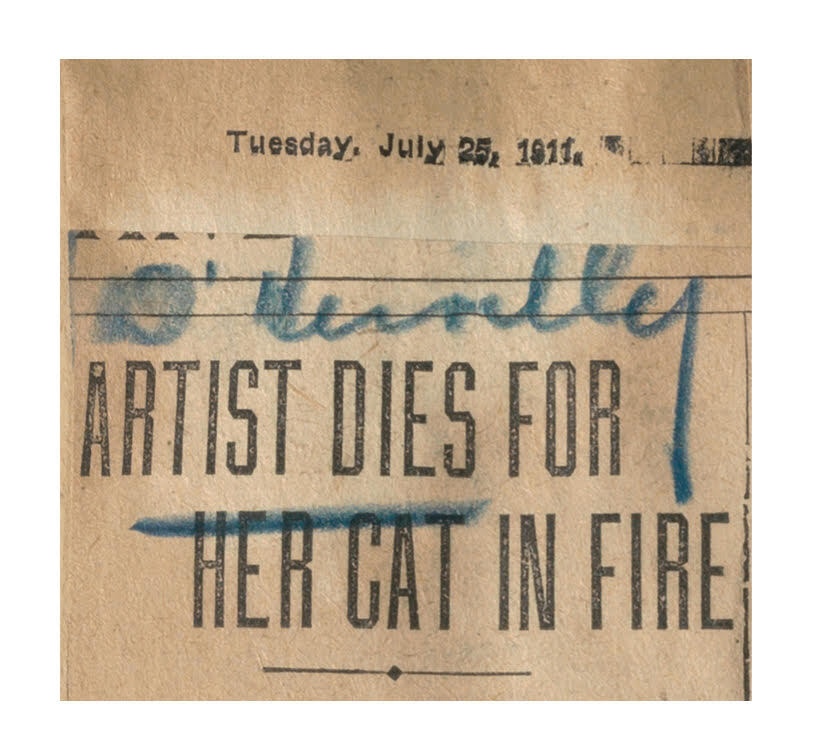

Compiled from 1906-1929, they not only memorialize the subjects of the obits; they also exhibit sensationalized reporting typical of the heyday of yellow journalism. As an archivist, I understood that the scrapbooks contained news that could be useful to historians and that might also inspire fresh creative work now and in the future. From a twenty-first-century perspective, the fascinating qualities of this collection were abundantly clear, but I was driven to understand its original purpose at its inception and throughout the years of its creation.

The twentieth-century obituary collector seemed a kindred spirit to Vasari, his Renaissance forebear, just as obsessed with heaping up biographical data that might delineate the contours of an art historical epoch. By odd coincidence, the scrapbook clippings appear in chronological order by death date, rather than an alphabetical or other organizational principle, mirroring Vasari’s arrangement in his Lives.

Like Vasari’s biographies, the scrapbooks present beguiling, colorful vignettes of the rough and tumble bohemian milieu, rife with passion, intrigue, and occasional violence. The cumulative effect of reading through hundreds of dead artist profiles felt very much akin to wading through Vasari’s daunting masterpiece: it was enlightening and exhausting. I wondered if the maker of The Met scrapbooks had deliberately aimed to create a modern-day-analogue to Vasari’s Lives—and I began to think of this work as Deaths of Artists.

Vasari described many artists’ deaths in a moralizing tone. He associated unfortunate or even miserable circumstances that some faced at the end of their lives with creative weakness, and he used history to settle old scores with enemies and antagonists. He derided a fellow Florentine, Jacone, as lazy and more interested in partying than cultivating his artistic ability.

Vasari dismissed this minor talent and his friends as “swine and brute-beasts…filthy and brutish in mind as their outward appearance.” One consequence of a disorderly life, Vasari suggested, was a squalid death. “Finally… reduced by infirmity… poor, neglected, and paralyzed in the legs… Jacone died in misery in a little hovel… on a mean street.”

Vasari characterized others as impoverished, eccentric, or suffering from delusions that hindered the full flourishing of their genius. In Vasari’s estimation, Paolo Uccello, a talented fifteenth-century painter, frittered away his gift by doggedly “seeking to solve the problems of perspective” and squandered his last years as a homebound recluse, chasing an elusive vanishing point to the grave. The lesson was that “Artists who devote more attention to perspective than to figures develop a dry and angular style because of their anxiety to examine things too minutely; and moreover, they usually end up solitary, eccentric, melancholy, and poor, as indeed did Paolo Uccello himself.”

The tabloid-style reporting by writers of the early twentieth century is consistent with a long tradition of such storytelling about artists.

Vasari even detailed a self-destructive eccentricity of his great hero Michelangelo, who “wore buskins of dogskin on the legs, next to the skin, constantly for whole months together, so that afterwards, when he sought to take them off, on drawing them off, the skin often came away with them.” By relating anecdotes like these, he affirmed and popularized stereotypes of creative personalities that have endured for centuries. Reading Vasari in tandem with The Met scrapbooks confirmed that the tabloid-style reporting by writers of the early twentieth century is consistent with a long tradition of such storytelling about artists.

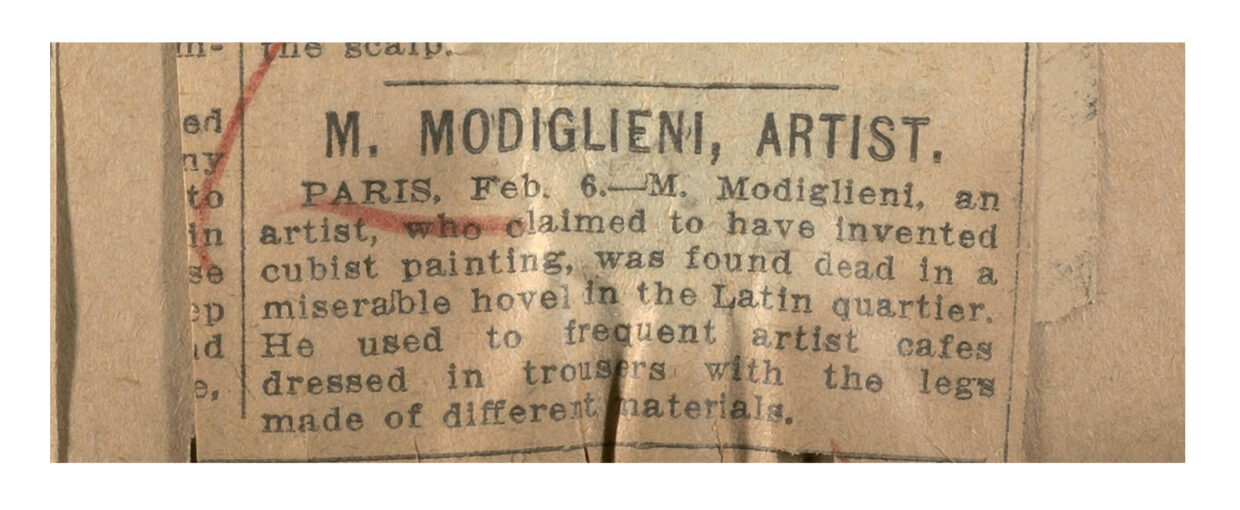

M. MODIGLIENI, ARTIST

M. Modiglieni, an artist, who claimed to have invented cubist painting, was found dead in a miserable hovel in the Latin quartier. He used to frequent artist cafes dressed in trousers with the legs made of different materials.

In a mere two sentences a 1920 news story reported to American readers the death of a little-known avant-garde artist, “M. Modiglieni.” Today this Italian artist’s name, Amedeo Modigliani, is anything but obscure; one of his paintings fetched $170 million in 2015. Modigliani, the quintessential bohemian, had been a notorious character on the Paris art scene. Like Jacone, he was a hard partier whose appetite for alcohol and drugs wrecked his already fragile health and cut short a promising career.

When Modigliani perished of tubercular meningitis at thirty-five, he was destitute and his pictures were unknown beyond a small circle of cognoscenti. The tragedy was magnified the day after his passing when his partner and most frequent model, Jeanne Hébuterne, also a painter, twenty-one and pregnant with their second child, leapt to her death from the window of her parents’ apartment.

Friends aspired to create a lasting memento to Modigliani by casting a death mask from his corpse. They nearly botched the job, tearing skin from the face and winding up with a poor likeness. From the wreckage, sculptor Jacques Lipchitz patched together a version serviceable to cast multiples later acquired by private collectors and museums, including one now in The Met. Modigliani’s funeral was thronged by Montparnasse locals including Pablo Picasso, Fernand Léger, and Constantin Brancusi.

The spectacle drew the attention of a journalist who filed the poorly fact-checked story that is glued to the bottom margin of a scrapbook page. In addition to misstating the artist’s first-name initial and misspelling his surname, the obituary wrongly associated him with Cubism and mislocated his place of death as a hovel rather than a hospital. Finally, it raised an eyebrow at Modigliani’s fashion sense, echoing Vasari’s description of Jacone as “brutish” in “outward appearance.”

One day I noticed a significant detail that I had overlooked during many prior viewings of the scrapbooks. Almost every clipping was marked with a bold stroke of blue pencil that underlined the word artist where it first appeared in each text. Additionally, scrawled across many obituaries was D’Hervilly, or sometimes D’H. I wondered—could this be the surname of someone at The Met?

I searched in old file card indexes in The Met archives and I quickly found a match for the unfamiliar name that led me to a dusty bundle of museum payrolls bound with thin, mauve twine. It looked like it had not been opened for a very long time. On a neatly penned ledger sheet from 1894 I discovered that an Arthur D’Hervilly was hired that year as a gallery attendant, the era’s parlance for a guard. I chased this hint and sifted through meeting minutes and correspondence of The Met’s first chief executive, where surprising details came to light. Over the next decade, D’Hervilly ascended the ranks and was ultimately appointed assistant curator of paintings around the time that the first artist obituaries were pasted into a scrapbook volume. I resolved to uncover all that I could about him.

__________________________________

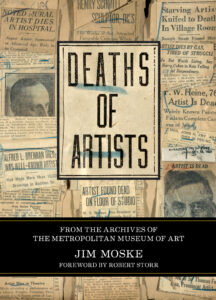

From Deaths of Artists by Jim Moske. Used with permission of the publisher, Blast Books. Copyright © 2024 by Jim Moske.

Jim Moske

Jim Moske is an archivist and writer based in New York City. He was Managing Archivist of The Metropolitan Museum of Art from 2008–23, and in earlier years was Archivist of the New York Public Library. Jim has published on topics including artwork provenance and transformational moments in the Met’s past. Deaths of Artists is his first book.