What Lies Beneath: The Deep Geology of Prose

Elizabeth McKenzie on Writing About Her Geologist Mother

While writing my novel The Dog of the North, I found myself preoccupied with geology. One of the characters is based on my geologist mother, which led me to re-immerse myself in how she viewed the world. Her career included time with the USGS and the National Park Service as a Ranger Naturalist, and her interest in the formations that make up the earth had long spilled over into our lives.

We were often sent into the Grand Canyon to observe naked cross sections of geologic history, from the light gray Kaibab Limestone at the rim to the dark and glossy two-billion-year-old Vishnu Schist along the Colorado River below. We spent many days on trips in the southwest hunched over, scanning the ground for crinoids and petrified wood. When I was living in Vermont, she came to visit and spoke animatedly of the glacial drumlins she’d seen flying up the Hudson Valley. Her passion for the stories told by the land brought her eventually to Australia, where she immigrated and spent the rest of her life.

There, I recalled how she reacted to the landscapes in novels that weren’t ostensibly about geology—such as Voss by Patrick White, which tells the story of the doomed Leichhardt expedition in the Australian outback in the mid-nineteenth century—marking up pages with comments on the topography.

The Australian chapters in The Dog of the North arose from this personal history, and took me on a research junket to the Barkly karst formations in northwest Queensland. A few lessons on the earth’s substance and structure were soon in order. Mostly limestone, karst formations like these are found across the world, laid down by ancient seas, composed of shells, sand and calcium carbonate, rife with fossils. Brittle, permeable by water, the terrain in these regions is riddled with caves and underground pools. It’s prone to crumble and collapse—which suggested all sorts of narrative possibilities.

Image Credit: James R. Cox.

Image Credit: James R. Cox.

But symbolic possibilities also presented themselves. When limestone, a sedimentary rock, undergoes pressure and stress, the calcite in it crystallizes, and those crystals in its molecular structure interlock into a tight matrix. And thus the rock becomes something else entirely. It’s now metamorphic. Limestone becomes what we know as marble. Sandstone under these conditions becomes quartzite. Shale becomes slate. Harder substances, beautiful, enduring. Had my mother ever mentioned this? Maybe, but I guess I hadn’t been listening.

As I worked over my manuscript, roughing it up from every direction, the forces of the earth on my mind, I began to see a metaphor taking shape to do with the importance of subjecting our prose to metamorphic conditions if we are to write novels that become more than the sum of their parts. And that while we may believe we’ve reached our goal when we achieve “limestone,” in itself an accomplishment for a novel in progress, we should push on with all the resources at our disposal to transmute the work to the next, more luminous stage. To apply intense, unflinching pressure to every aspect of the work in progress, subject every participating component to the heat of judgment. Stress our base materials to such a degree that they move towards crystallization, towards marble.

In other words, a process beyond what we think of as revision.

Everyone has their methods. I might start with appraisals at the word level. Which are empty, filler. This noun is too general. That verb is flat. Then move on to syntactics: this phrase here, not there. Then dynamics: This paragraph has no spring, no life. Have I told it slant, so that it topples inevitably into the next paragraph? Then tonal: Does it evoke anything—humor, sorrow, joy, darkness, light—or is it merely a slab of print? Then acoustical: Does it have rhythm, does it have music? Then content: What really happens in this sentence, this paragraph, this page, this chapter? And so on. I’ll read it aloud, or I’ll switch fonts and see it anew on the page. Leave no stone/word unturned.

And so at what point comes this hoped for metamorphosis? I think I know when it happens for me. It’s when I finally pick up the work and think, who wrote this? All of those bits and pieces and decisions became this? It’s like alchemy, almost magical.

I didn’t have much interest in geology when my mother was alive. I made fun of glacial drumlins. When she moved to Australia she left behind a storage locker that, years later, I had to empty out after she was gone. I’d expected to find household items deemed unworthy of shipping to the southern hemisphere, but no, the locker was filled with rocks.

They weren’t labeled, though some I recognized like old friends. Notable cobbles from riverbeds that had once been placed around our yard in LA (and are now in mine). Mineral specimens, fossils, canvas sacks of agates and geodes. I had no idea where they came from and since I couldn’t ask her, I understood that identifying them was up to me. Strangely, now all of a sudden I’m looking for the geological everywhere, even in metaphor. I want to know what lies beneath everything, and how it came to be.

__________________________________

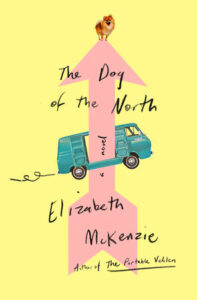

The Dog of the North by Elizabeth McKenzie is available from Penguin Press, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.

Elizabeth McKenzie

Elizabeth McKenzie is the author of the novel The Portable Veblen, which was longlisted for the National Book Award and shortlisted for the Baileys Women’s Prize; a collection, Stop That Girl, shortlisted for The Story Prize; and the novel MacGregor Tells the World, a Chicago Tribune, San Francisco Chronicle, and Library Journal Best Book of the Year. Her work has appeared in The New Yorker, The Atlantic, The Best American Nonrequired Reading, and was recorded for NPR’s Selected Shorts.