What Lies Behind the Postcard: Jasmin Iolani Hakes on the New Meaning of Summer Reading

“Novels have the ability to transport, but they can also deepen our understanding of a place in a way that is difficult to replicate.”

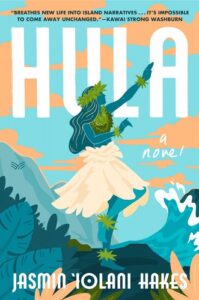

A couple of months ago, my team and I started circulating the uncorrected proofs of my debut novel Hula, in the hopes of building up some early support. The story is set in my hometown of Hilo, Hawaiʻi. I’m used to people sharing any anecdotes they have about Hawaiʻi when they learn where I’m from, so I was expecting those. What I wasn’t expecting was how many people said they wished they’d read Hula before their visit to the state.

My novel comes out in early May, just in time to be categorized as a “summer read.” I had mixed feelings about that. I’ve always considered “summer reads” to be light and entertaining, books I can slip in and out of while I nap under a sun umbrella somewhere, even if that somewhere is my backyard. Hula asks a little more of a reader, offering a complex, intimate perspective on a place too often reduced to a tropical playground for those who can afford the trip. It’s a peek behind the postcard, if you will.

Novels have the ability to transport, but they can also deepen our understanding of a place in a way that is difficult to replicate, and that was one of my goals when writing Hula. So what if we started looking at our summer reading list as an opportunity—not just to escape, but to turn our vacations into meaningful, enriching trips that stay with us long after our suitcases return to their dusty corner of the garage?

Reading gave me a chance to see what awaited on the other side of the horizon.

Sometimes a novel’s setting sits in the dim distance. Whatever happens in its pages could take place in Iowa as easily as in Italy, the spotlight of the author’s attention fixed on some element of the universality of human experience rather than the characters’ surroundings. But in other stories, the setting is as integral to the plot as the characters are. Or maybe the place is one of the characters. A bus. A train. An assumed-to-be deserted island. Those are the books I tend to connect to most.

My love affair with reading about other places began long before I recognized it as such, but by the time I was in high school it was undeniable. Instead of participating in spirit days and recess shenanigans, I spent my senior year attending school only in the mornings. At lunch, I headed to the Hilo Public Library and dedicated the afternoon hours to reshelving returned books. I developed a system, hustling up and down the aisles, slipping books in their proper spots quick as a flash so I could spend at least part of my time diving into one of the many worlds that filled the shelves, just waiting to be devoured.

I enjoyed the stories, yes, but for a girl on an island where everywhere else is a long expensive flight away, this was more than a way to escape. It was an education. Reading gave me a chance to see what awaited on the other side of the horizon. And even if my life never took me to all those places, I felt like I knew a bit of what locals ate, how they spent their holidays, how the people in their neighborhood interacted with each other, what kept them up at night with worry, and what they dreamed of being when they grew up.

I read Things Fall Apart by Chinua Achebe. Once Were Warriors by Alan Duff. The Kite Runner by Khaled Hosseini and The Woman Warrior by Maxine Hong Kingston. Midnight’s Children by Salman Rushdie and The House of the Spirits by Isabel Allende. These books don’t pull any punches. You get political power plays and mythology, socio-economics and cultural nuance, local biases and superstitions. Heritage and legacy and identity politics. But also human desires and needs and challenges that transcend geography.

A seed began to sprout. Of a book that somehow captured Hawaiʻi’s multifaceted social fabric the way Rushdie and Allende, Duff and Hosseini, Kingston and Achebe did in their own. Dream big, as they say. Even pre-internet, there was never a shortage of tourist destination compilations for Hawaiʻi. I knew just how accurate these were (not very), a knowledge that whittled away my faith that similar lists had anything to offer in regards to all the elsewheres I dreamed of experiencing. But these novels. They gave me something akin to memories. A sense of familiarity.

I admired these writers, and many others, for offering me the literary equivalent of an invitation into their home—asking me to remove my shoes at the door, offering me a seat at the kitchen table, introducing me to all the relatives, and then letting me observe their everyday lives the way I would if I suddenly found myself in a country I’d never heard of, surrounded by people speaking a language I don’t know.

At these moments, my brain wakes up to the challenge. I start picking up on tone and inflection, body language and context. My other senses activate, noting smell and taste and sound and nuance. By the end, I have a picture for my scrapbook but also an imprint on my person.

Hawaiʻi is a place many people feel they know, but don’t.

I wish I could have asked them how they did it. That’s some heavy lifting. How did they refer to events I wasn’t familar with, make cultural references I didn’t know, and get me to clearly understand what was at stake without expressly explaining any of it? How did they decide how much they were going to make me work to understand versus how much they were going to hand me on a platter? How did their characters code-switch and not shut me out to the point where I might lose my grip on what was happening?

Hawaiʻi is a place many people feel they know, but don’t. People can go to Hawaiʻi and buy a tour. That Hawaiʻi is easily accessible. But if I was going to write something that equated to an invitation into my home, I was going to have to toss the glossary, the italics, and the tempting footnotes—all the accoutrements of the minority, indicators of something that needs to be explained, the exotic fruit that has suddenly appeared in your fruit bowl among the apples and oranges. At this table, you don’t get flash cards.

While there are still many geographic gaps in the canon, in recent years I have noticed more books, ones that might have once been quietly published as niche multicultural offerings, at that highly coveted table at the front of the bookstore, standing proud in the mainstream. And if we keep reading books that are windows into other worlds, written by those who are from those places or know them intimately, we will be rewarded with even more places to go.

Summer travel and summer reading can be one and the same. Writers, keep writing outside the margins. Write what you know, yes. But also, write where you know. Take me home with you. Invite me over. Readers, join me. Let’s add to the way we participate in and with the wider world. Let’s let these books take us where no airplane ticket ever could.

__________________________________

Hula by Jasmin Iolani Hakes is available from HarperVia, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

Jasmin Iolani Hakes

Jasmin Iolani Hakes was born and raised in Hilo, Hawai'i. Her essays have appeared in the Los Angeles Times and the Sacramento Bee. She is the recipient of the Best Fiction award from the Southern California Writers Conference, a Squaw Valley LoJo Foundation Scholarship, a Writing by Writers Emerging Voices fellowship, and a Hedgebrook residency. Dance has always been central to Jasmin's life and creativity. She took her first hula class when she was four years old and danced for the esteemed Halau o Kekuhi and the Tahitian troupe Hei Tiare. She worked throughout college as a professional luau dancer. She lives in California.