What Kendrick Lamar’s Pulitzer Win Meant For American Music

Dr. Todd Boyd on Hip Hop’s Long Journey to American Cultural Dominance

When Nas described himself as the “most critically acclaimed Pulitzer Prize winner / Best storyteller / Thug narrator / My styles greater” on his song “Hate Me Now” (1999), he was foretelling something monumental on the horizon. The Pulitzer Prize for Music is considered one of the nation’s most distinguished honors. First awarded in 1943, it recognizes “a distinguished musical composition by an American that has had its first performance in the United States during the year.”

During the prize’s first eighty years, the award for music was given annually except on four occasions, in 1953, 1964, 1965, and 1981, as the jury decided that no singular work was deserving of it. However, in 1965 they recommended that a special citation be awarded to Edward Kennedy “Duke” Ellington for his entire body of work. Ellington is arguably the United States’ greatest composer and one of the most important figures in the history of American music.

Yet, in spite of the jury’s unanimous recommendation, the Pulitzer advisory board rejected the endorsement and decided against giving out any award that year. Two jury members eventually resigned in protest.

When the board informed Ellington of the rejection, he responded in an especially Ellingtonian way, famously stating, “Fate is being kind to me. Fate doesn’t want me to be too famous too young.” He was sixty-seven years old at the time. Speaking further in a September 12, 1965, New York Times Magazine article, Ellington would highlight the bias inherent in his chosen genre: “I’m hardly surprised that my kind of music is still without, let us say, official honor at home. Most Americans still take it for granted that European music—classical music, if you will—is the only really respectable kind.”

It wouldn’t be until 1997 that Wynton Marsalis would become the first jazz artist to win the Pulitzer Prize for Music for his epic work “Blood on the Fields,” with Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra. Ironically, Marsalis’s oratorio, like a great deal of his work with the orchestra, was largely inspired by Ellington.

The Pulitzer took a surprising turn when it was announced in 2018 that rapper Kendrick Lamar would be the recipient of the music award for his album DAMN. (2017). Kendrick was the first musical artist from a genre other than jazz or classical to earn this honor. So while Nas’s “Pulitzer Prize winner” proclamation might have sounded simply like hip hop braggadocio, he was onto something. Kendrick was the one who fulfilled the prophecy.

The journey from residential rec-room parties in the Bronx to Pulitzer Prizes, The White House, and The Super Bowl has been a long and storied one.While the slighting of Ellington was indicative of the racism and cultural bias that existed in the 1960s, the recognition of Kendrick’s work made the Pulitzer board appear open-minded and culturally connected. Jazz and hip hop share certain similarities in terms of how both genres have at various points been dismissed, ignored, marginalized, stereotyped, and regarded as threatening, before proving all of this negativity wrong via their individual successes.

The difference is that jazz, unlike hip hop, was more a cultural success than a commercial one, and came to be associated with high art and the height of musical sophistication. Ellington was an elder statesman, who was dissed after creating a hugely impressive body of work over a career spanning multiple decades. Kendrick, on the other hand, is a contemporary artist who was recognized with a Pulitzer relatively early in his career. This is no slight on jazz: the music has always been over the head of the masses, appealing to the hip, while marginalizing the square. Instead, it is a testament to how transformative hip hop has become, managing to remain popular while also, eventually, achieving the broadest critical acclaim.

Three years prior to the Kendrick’s historic award, President Barak Obama announced that his favorite song of the year was “How Much a Dollar Cost,” from the Grammy award-winning album To Pimp a Butterfly. This was followed by an invitation to the celebrated rapper, from Compton, California, to meet with the president at the White House.

Obama’s senior advisor, Valerie Jarrett, reported that the president had said to the young artist: “Can you believe that we’re both sitting in the Oval Office?” In this statement he was acknowledging the historical implications of being the nation’s first Black president and that the weight of his influence and ability to shape the culture directly resulted in these two Black guys occupying a space previously considered out of reach.

Obama’s acknowledgment of and appreciation for a cutting-edge figure like Kendrick Lamar demonstrates a cultural competency never before associated with the White House or with politics in general. In a society where culture serves such an important purpose, the lack of formal respect for this purpose is often disappointing.

It was for precisely this reason that the legendary musical giant Quincy Jones lobbied Obama to create an ambassador for the arts, a secretary of culture. While this did not come to be, Obama’s continued cultural engagement, throughout his presidency and beyond, indicated that such considerations were most certainly worthy of attention.

While Kendrick went on to become the first rapper to win the most prestigious prize in literature, hip hop’s mic drop, relative to this story, would occur during the halftime show of Super Bowl LVI at Inglewood, California’s Sofi Stadium on February 13, 2022. Led by Dr. Dre, and also featuring Snoop Dogg, Mary J. Blige, Eminem, 50 Cent, and Kendrick, the landmark performance represented another first—the first Super Bowl in history to focus exclusively on hip hop. There was no way in hell that Dr. Dre and Snoop Dogg would be afforded the opportunity to perform on the Super Bowl stage in 1993.

Gangsta rap, with its direct connection to the streets, was simply too controversial to be allowed to participate in such a mainstream cultural space, but as hip hop’s dream grew and evolved, ultimately and against all odds reaching a point of cultural dominance, it amassed enough clout to be able to remix the American dream in such a way that it created a new version for those who were once denied it.

The journey from residential rec-room parties in the Bronx to Pulitzer Prizes, The White House, and The Super Bowl has been a long and storied one. Inherent to this trajectory is the desire to rise up, the ability to transcend, the impulse to prevail.

__________________________________

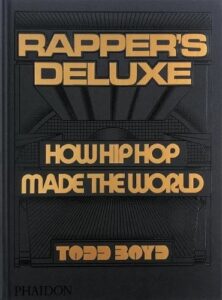

Excerpted and adapted from Rapper’s Deluxe: How Hip Hop Made the World by Dr. Todd Boyd. Copyright © 2024 Reproduced by permission of Phaidon. All rights reserved.