What It Means to Write About Motherhood, Part Two

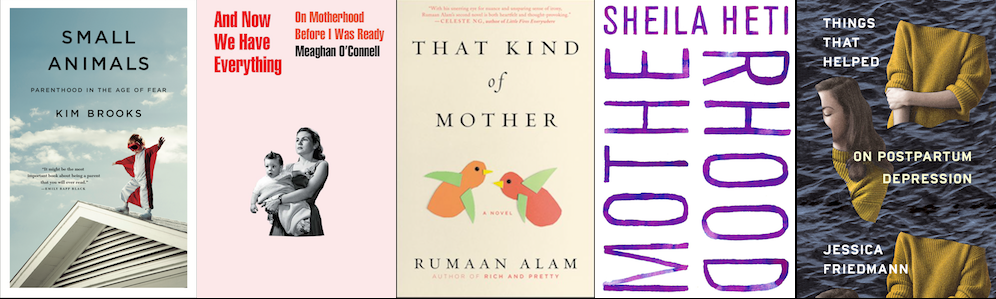

With Kim Brooks, Rumaan Alam, Sheila Heti, Meaghan O'Connell

and Jessica Friedmann

In this roundtable, five writers discuss what it means to write about motherhood. Read part one here.

Rumaan Alam, That Kind of Mother

Kim Brooks, Small Animals: Parenthood in the Age of Fear

Jessica Friedmann, Things That Helped

Sheila Heti, Motherhood

Meaghan O’Connell, And Now We Have Everything: On Motherhood Before I Was Ready

__________________________________

Kim Brooks: In “One Hundred Essays I Don’t Have Time to Write,” the playwright Sarah Ruhl asks the questions, “Must one enjoy one’s children? …How much must we enjoy them? I love these questions, because they gesture toward one of the most psychologically thorny aspects of motherhood, the pressure not just to have kids and not just to take care of them and love them, but to love loving them, to love everything about this role, to sacralize it in a sense, no matter how much strains other relationships or other areas of your life. There is a coercion of feeling around motherhood, a compulsory sentimentality. Do you ever worry you don’t feel about motherhood or parenthood the way you’re supposed to feel about it? What function does the sentimentalization of motherhood or parenthood serve? Have you experienced much shame or anxiety when it comes to parenting? And what are the “consequences” when these thoughts are put to paper?

Rumaan Alam: I think plenty of writers have taken a different, more considered view of parenting than the mawkish middlebrow, but the sentimental is the most popular or prevalent register for writing about parenthood. It’s like romantic love; sure, there are the boy meets girl stories, but there are plenty of other ways to write on that subject. Personally, I’m not sure there’s transcendence in the moment your kid barfs down your shirt and all over your bare back. But maybe there is, what the hell do I know? True, if you write about the complex reality of parenthood, people might think you’re a monster, because everyone is invested in the myth of sentimental parenthood; I guess you have to decide whether you can live with yourself after telling the complicated truth.

Meaghan O’Connell: God. The sentimentalization of parenthood upholds the status quo and makes you feel guilty or feel whiny or entitled for wanting more or feeling dissatisfied. I think I’ve successfully internalized that by now, but it’s breathtaking witnessing it in other people, their insistence that everything is great and these are the days and let’s soak it all up. I figure some people are just lucky and content, some people are lying, and some people are completely repressed. I mean what could be more sentimental than my relationship with my kids, but that’s between us, not us and the state, or us and the general public. And it feels unrelated to or in spite of the fucked up culture and impoverished social structures we live and make do in.

I wanted to say that I generally feel confident that if or when I am feeling some non-status-quo way about parenting, I know I must not be the only one. That confidence is what enables me to write. But that act of writing is a defiance. I still experience that initial discomfort. Just a few weeks ago I was sobbing in therapy about hating breastfeeding and feeling like that meant I was somehow unmaternal at my core. I knew, intellectually, that was ridiculous. I mean, I already wrote a damn book about it. But here it was again.

I am artistically fascinated by that gap between how we should feel and how we do feel, and that’s because I have such trouble with it in my own life.

I am artistically fascinated by that gap between how we should feel and how we do feel, and that’s because I have such trouble with it in my own life.

So to answer the question, sure I have anxiety and shame about parenting in the day to day (my kid needs a haircut, I should have gone to the grocery store, I wish I hadn’t snapped at him, etc), but when I step back and consider my parenting, or maybe more importantly, my relationship with my kids, I feel good about it/them/myself. Usually once I have written about something, it’s been worked through to the point where I feel fairly untouchable, to be honest! I have made peace with whatever I’m grappling with, and if the reader brings their shit to it, well, that’s what it’s there for.

Jessica Friedmann: What I think about a lot is how atomized parenting has become, and how alienated most adults are from the idea of friendship with a child. It’s something I am trying to write about at the moment, and thrash out in fiction; this idea that the adult-child relationship has shrunk to some very specific and culturally acceptable formats or conventions in the last fifty years or so. Obviously the love you feel for your own child is very specific, but I wonder if the intense pressure we currently feel to enjoy it and feel completely fulfilled by it is partly a response to that narrowing of the village.

One of the things I enjoy most about being a parent is being trusted by my son’s friends, getting to know them, having this diffuse gang of kids I am in some way responsible for. I feel like a generation or so ago if you were the postman or worked at a milk bar or were a lonely old woman, it was more acceptable to cultivate relationships with children and enjoy them. Whereas now that enjoyment is condensed down to the one or two or three that you yourself have, and you are supposed to guard them almost xenophobically.

Sheila Heti: In answer to “what function does the sentimentalization of motherhood or parenthood serve?” I think it partly serves to convince people to take on these roles. The more that motherhood is a sacred and sentimentalized role, the more it becomes a kind of sacrilege to refuse it, anti-social, and comes with shame. As a woman especially, you are separating yourself from something holy and pre-chosen for you—chosen for you, unquestionably, if you biologically can.

My friend once made a good and rational point—he said that societies that don’t romanticize and idealize this role probably don’t stick around as long as societies which do.

I don’t know if it will ever be the case that humans can wash from the word Mother the symbolic associations of pure love and pure givingness; meaning one of the functions the ideal serves is to give us hope (that such a love can be). Perhaps the aim should be for us to more definitively separate the universal symbol of Mother from the lived experience of the mother—which I think many contemporary writers on motherhood are striving to do. It’s important, because the sentimentalization of motherhood allows society not to help mothers. The sentimentalization of motherhood allows us to turn away from caring for mothers, because it leads us to believing that motherhood is so rosy, so innate, such a given happiness, that the mothers don’t need our help.

I am also a huge admirer of Sarah Ruhl’s book, in particular on one of the first pages where she writes”

I could lie to you and say that I intended to write something totalizing, something grand. But I confess that I had a more humble ambition—to preserve for myself, in rare private moments, some liberty of thought. Perhaps that is equally 7.

My son just typed 7 on my computer.

It seemed like the invention of a new, absurdist form—some kind of Oblique Strategies command or an Ouliopian restriction. How beautiful! And though I don’t have children myself, one of my unlived fantasies of having them and writing a book is that I would have to come up with a new form (as Sarah gestures to in this essay) to accommodate all the restrictions on time and extended periods of thought that motherhood would bring. Rachel Cusk, for instance, has spoken about how she, because of being a mother, had to learn to write her books entirely in her head over the course of several years, finally writing them down quickly on the page during her four weeks on leave from parenting (I suppose when they were with her ex?). This strategy led to this latest, brilliant trilogy of hers. Did any of you find new literary forms as a result of the work of parenting, as Ruhl enacts in her book? Or new ways of creating, as Cusk described?

Jessica Friedmann: Children are innately absurdist and that is the very best thing about them. Their language development is so rich in unexpected similes and little utilitarian work-arounds. It’s an ongoing stimulating flow of language that can sometimes drive me crazy but often sparks up some corresponding sideways approach in my own brain.

In terms of form, I wrote almost the entirety of this book in the Notes app on my phone. Sometimes at parks, pushing the swing one-handed; sometimes at the supermarket; very often at 2am when a thought worked its way to the surface and needed to be expressed. Most of these notes were cryptic fragments that had to be pieced together again once I got the time to sit at my computer, but having a smartphone was amazing. I don’t know how much research I managed to sneak into otherwise dead hours when O fell asleep on my arm.

Now that he is reading and writing, I am constantly astounded by how intuitively he navigates keyboards and phones. He loves making paper books at the moment, but while he was learning to read he insisted on typing on the iPad, picking out his letters with one finger like an old man, which I didn’t realize was because we have the predictive text feature enabled there. His stories from that time period are a glom of words he has sounded out, words he has ‘predicted’ whether incorrectly or correctly, illustrative emojis which enhance the meaning of a sentence, and emojis (which he calls ‘symbols’) that take the place of nouns. There’s some formal logic to it but for the life of me I can’t figure out what it is. It’s fascinating!

Sheila Heti: Oh wow I would love to see that! Can you show us?

Jessica Friedmann: It’s mostly this kind of thing — about his toy bunny, Bunny:

Bunny eats carrots and let-es and egg-plants ??

Bunny likes playing soccer-ball ⚽️

Bunny also likes playing Bunny tag ??????

Bunny driks water ??

Bunny likes to nap at nap 8o -clock 800?

Bunny likes to make a show ???

I think he’s dropped the emoji-as-noun as he gets more confident with language; I haven’t seen that usage lately. Wouldn’t the concrete poets have loved emojis?

Sheila Heti: Damn, why haven’t we been using emojis in this conversation?

Kim Brooks: I’ve read that there is a renaissance of writing about motherhood. Do you agree, and if so, to what do you attribute it? What books on the subject have influenced you most?

Rumaan Alam: I haven’t read enough to be an authority on this question. Many, many writers I adore have written beautifully about motherhood—Lorrie Moore, Louise Erdrich and Laurie Colwin, sure, but then I think of how Anita Brookner wrote about being a daughter, or how Willa Cather wrote about being a father or how Jonathan Franzen wrote about modern motherhood (the only good part of Freedom). But I don’t know which influenced me, and I wouldn’t want to insult the writers I love by claiming them as having influenced whatever it is I am trying to do.

Meaghan O’Connell: Rachel Cusk, Eula Biss, Maggie Nelson, Jenny Offill— the usual suspects are big ones for me. Of Woman Born. Shirley Jackson. Ursula LeGuin has written some amazing stuff about motherhood and writing that I always think about (there is this great small press anthology called The Mother Reader that I really recommend.)

I would say there has been a lot of rich writing about motherhood lately, and that maybe publishers have been more willing to publish it the past few years, and that it seemed, for a few months this year (around mother’s day, naturally), that there was a “glut” and it was starting to annoy people on Twitter and/or that it was a useful organizing principle or cultural peg for critical essays. Motherhood has always been a subject, it’s just often been considered niche and people tend to “discover” it when they become parents themselves. “Why does no one talk about this?” is the famous new mom refrain. And everyone who has come before is like, Ugh, we have been but you just weren’t listening. (I say this having been a classic offender myself!)

I think there is something to Sarah Blackwood’s essay about treating motherhood as a special-interest subject that as readers we can say we care about or not. Rather than integrating these books into whatever genre or form or sensibility they exist in. Like Jessica said above, I get a little deflated seeing my book in the Parenting section at Barnes and Noble, next to What to Expect. “Maybe this is where my people will find me,” I tell myself, though I have never gone looking for what I am trying to write in the parenting section.

“Look at all these mom books!” does not feel much like progress to me, or not of the kind I am interested in! It’s just marketing. Of course I’m grateful to have some sort of market, but one hopes it goes beyond that.

Jessica Friedmann: I love that Sarah Blackwood essay. I want her to be my friend! If there is a specific motherhood zeitgeist, I think it’s that so many of us feel as though we’re facing the same, new and terrifying pressures; a crumbling ecology, a politics that has seemingly gone off the rails, “millennial” financial structures that undermine our ability to experience economic stability, and so forth. How does one bring a child into this world? Is it ethical? Probably not, but we’ve done it… so now we have to learn how to live with the fact.

The books I turn to in order to do this are generally memoirs of mother-writers in similar situations. Ruth Park propping her typewriter up on her ironing board while raising a gang of kids in post-war Sydney poverty. Rumer Godden getting up at 4am to put a couple of hours of writing in before her daughters woke, making ends meet as a single mother in rural Nepal. Nora from Monkey Grip holding down the fort while Javo goes out and gets high, and trying to integrate her work at a feminist magazine with raising Gracie and generally living a bohemian and beautiful life. The common thread is that creative work for these women was seen not as an indulgence but as a lifeline. I think that is the way of it for a great many of us, maybe now especially.

Rumaan Alam: Please allow me the opportunity to boast that Sarah Blackwood actually is my friend. She’s as cool in life as she is smart on the page. I also want to note that Louise Erdrich’s The Blue Jay’s Dance is a lovely book about motherhood because it encompasses so much more; Erdrich declines to be simply a mother or a mother torn between that and art. She is, on those pages, a full person, a real person. I think this is probably the kind of thing that has been reckoned with, generation after generation, but women of generations past weren’t as free to write this down for a zillion terrible reasons we can just shorthand as “the patriarchy.” Every work of art is its own particular thing, the product of a distinct experience and sensibility, but there are really no new feelings under the sun.

Sheila Heti: Perhaps slightly differently from others on this panel, my book isn’t about being a mother—it’s about deciding whether to become one, and the desire not to, and existing as a woman with a sort of negative identity (non-mother) that is the inverse of someone else’s positive identity. Rachel Cusk’s A Life’s Work felt like it opened a door, in terms of its courage, but for the most part I felt I was writing my book in the face of bafflement at books like Maggie Nelson’s and Sarah Manguso’s and Rivka Galchen’s and others, which deal with the intensity of having a child, but do not really ask why a child at all? For me, there is a huge ethical and personal dilemma which comes before the struggle-with-motherhood, but which has been mostly or entirely left out of these otherwise interesting books, and it was this gap that compelled me.

There are books I read which press on the assumption that to make a life is an inevitable good: David Benatar’s Better Never to Have Been is one. He actually says it’s unethical to make a human life, because of the tremendous suffering that comes with life. What could be a greater act of love for one’s child than to allow them to exist unborn? I was also interested in the thinker Lee Edelman, whose book No Future considers queerness as a kind of refusal to fall into the sentimentality that directs most (heterosexual), politically-minded people to unquestioningly evoke “the future” as the tense of most importance, in terms of where action in the world can happen—this future embodied in the romantic image of the child. But what about the present? Why do we need to evoke a child to talk about care for the world?

Ultimately in my novel, I wanted to paint the mind of a single woman in a heterosexual relationship, surrounded by conventional actors, and the stress and indecision of choosing against having a child in this context; a woman all alone, without any models to look to, trying to configure an ethics around an existential relationship to one’s ancestors, rather than one’s progeny.

Kim Brooks: I’ve been thinking a lot lately about how segregated children are in much of our society from adult life. I was recently recalling a party at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop from years ago. There was one woman in the program of fifty or so students who had a small child. She threw a party at her house and the kid just kind of hung out and colored on the floor while we all drank and talked and did whatever writers do at parties. His presence among us felt strange enough that I remember it all these years later, and now, as I’m writing about the need to better integrate children, and thus mothers, into public life, I wonder what affect the ghettoization of parenthood and childhood have had on writers ability to write about children. Children used to fill the pages of adult novels, and I don’t think this is the case any more, which is too bad, because I think writers and children have a lot in common—specifically a kind of un-self-conscious curiosity about the world, a deep, but often unarticulated desire to impose order on chaos. What do you think writers, parents and non-parents alike, can learn from observing or writing about children? As a writer, what interests you most about childhood, and how have these interests changed in relation to your becoming a parent or choosing not to become one?

Sheila Heti: I am completely uninterested in my own childhood. The person I was before I was fifteen years old is a complete mystery to me, and it’s not a mystery I’m interested in solving. I’m also not interested in childhood as a state; nothing could be more boring for me than reading about someone’s childhood.

I am completely uninterested in my own childhood. The person I was before I was fifteen years old is a complete mystery to me, and it’s not a mystery I’m interested in solving. I’m also not interested in childhood as a state; nothing could be more boring for me than reading about someone’s childhood.

What interests me most about your question is the idea of the segregation of children from adult society. I think it would be nice if it were more socially acceptable for adults to socialize with children apart from that child’s parents, but many parents I know would rather present them and their child as a unit. I have friends whose children I get along with, when I can’t say I enjoy the parent’s company, and if there was true integration, then the children and I could be friends without the parent as a constant interlocutor. I think it is often the parents who keep the child in a protected, bonded, isolated state, separate from the world, while at the same time often wishing that they weren’t so isolated in the work of parenting. I do know some parents who aren’t like this, but I think they are not the norm. I went out for Korean food with the eight-year-old daughter of a friend of mine and the girl was very happy to feel adult-like out in the world without her mother, sitting and eating everything she ordered; then when I brought her home, I’m sure she was happy to be a child with her mother again.

I can imagine the great fear parents have that prevents more of these sorts of interactions, but it would be wonderful if parents could encourage the responsible and trusted adults they know to have independent relationships with their children. Such relationships benefits the third-party adult, the parents, and the children. Margaret Mead wrote about the significance of “alloparents” in various cultures (a term for those who are not parents who also help care for the young), and that is not a role we hold a place for in our culture; the only “trusted” adults are those who are hired and paid.

Rumaan Alam: I think kids are animals, in a way that’s kind of distressing and that most adults hate to look at. Diane Williams has a story “Masters of the Universe” which dramatizes two boys playing with action figures in a way that is distressingly sexual and violent, and it feels very… accurate. In the end, the children close the door on their mother/observer, and it feels like a relief. I hate most writing about kids because it doesn’t acknowledge that kids are just the same as us, without the remove of propriety. I love kids, and wrote about kids a little in my most recent book, but I actually hate most fiction that is about kids because it rarely accounts for them as they truly are (also few writers really get at the idiosyncrasy of childhood diction and thought, and sometimes when they attempt it, it feels very twee and ridiculous). Kids aren’t governed by logic, I guess, and most fiction is.

I think kids are animals, in a way that’s kind of distressing and that most adults hate to look at.

Jessica Friedmann: Kids are absolutely bounded by logic! It’s what drives their incessant why why why why why: this tortured search for the cause and the effect. They can see and sense resonances between things without knowing the explicit link, which is what I find exciting because that’s what drives my writing as well. Not to ‘impose order on chaos’, but just to figure out what the relationship is between two or three seemingly disparate things.

One thing that I have really loved about being a parent is seeing how gentle my son and his friends are, how much they look after each other and have an ethic of care. It’s maybe a corollary to that violence Rumaan talks of, a kind of unmitigated sweetness, and it is very nice to have a source of it on tap. He has come over to see what I’m doing and is hanging over my arm right now. I am explaining that the question is about how writers and children are the same.

O, age six: From my fact, I know that they are small and big. They’re small in Kindy and they’re big in Year One, Year Two, Year Three, Year Four, Year Five and Year Six. About as adults. Well I know children love writing and writers too. That’s one fact I know. Some children wear glasses and some writers do also.

Sheila Heti: Wow, what a perfect place to end!

Jessica Friedmann: Oh, Sheila. It never, ever ends.