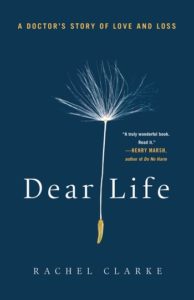

What if Medicine is Not About Preserving Life, But About Humanity?

Why Dr. Rachel Clarke on Facing the End of Life Every Day

In today’s developed world it is possible to live an entire lifetime without ever directly setting eyes on death, which, considering half a million Britons and two and a half million Americans will die every year, is remarkable.

Little more than a century ago, this distance from dying was inconceivable. We invariably departed the world as we entered it, among our families, close up and personal, wreathed not in hospital sheets but in the intimacy of our own homes. Now, though, both birth and death have become, by and large, institutionalized. The only two certainties around which our lives pivot have been outsourced to paid professionals.

A scant two percent of births in Britain are home births, and only one in five of us will die at home, despite two thirds of us expressing the wish to do so. Hospitals, hospices and care homes are the new repositories of modern-day demise.

Doctors, in involving themselves in matters of dying, therefore do something highly unusual. I am odder than most. By specializing in palliative medicine, I use my training and skills specifically to help people with a terminal illness live what remains of their lives as fully as possible, and to die with dignity and comfort. I have, in short, made dying my day job. Rarely, if ever, does a week go by in which all of my patients survive.

Most people’s reaction on learning what I do for a living is to wince as they mutter, “I don’t know how you can bear that.” You can almost feel the suppressed recoil as they shrink from the thought of all that death. And I don’t blame them. I used to recoil once too. Losing someone you love can be a pain more searing than any other. And there is no escaping the fact that dying, like childbirth, can be grueling—though far less commonly than I once imagined. As a patient once told me: “I’m not afraid of dying, I just never realized it would be such hard work.”

Were there really doctors who dismissed patients as trash, as having lives devoid of value, once medicine could no longer prolong them?

The allure of medicine is easy to understand. There is power, respect, status, gratitude. But why on earth would a doctor, after all those laborious years of study—the hard-won potential to restart a child’s heart, give back the gift of sight, reset a shattered limb, transplant a kidney—choose to immerse themselves in death and dying? What could possibly be the attraction of day in, day out grief and sadness, all of it tainted by the whiff of defeat, of inescapable medical failure?

If neurosurgeons are the rock stars of the medical hierarchy—its sexy, alpha, heart-throb heroes—then palliative care doctors are the dowdy support act. A low-rank medical speciality, we lurk in the shadows, too close to death for comfort, murkily intervening with our morphine and midazolam once our charismatic cousins have exhausted their efforts at cure. No one in the hospital is quite sure what we get up to, and usually does not wish to know either. Death is taboo for many reasons, not least the fear that it might just be catching.

Once, shortly after I qualified as a doctor, a consultant oncologist summed up in one sentence a certain old guard’s attitude to terminal diagnoses. We had just left the bedside of a patient whose cancer had spread widely, despite her last-ditch chemotherapy. “There’s nothing more for us to do here,” the consultant had said by the sink, as he literally and metaphorically washed his hands of her. “Send her to the palliative dustbin.”

His words left me dumbstruck. Were there really doctors who dismissed patients as trash, as having lives devoid of value, once medicine could no longer prolong them? At the time I could hardly conceive of a more repugnant sentiment, though today I wonder if the consultant’s remark was really a crass attempt at humor, born out of embarrassment and discomfort at his own perceived impotence. The feelings death stirs are nothing if not complicated.

Even I—someone who works with death on a daily basis—treat the subject with caution. My own children, for example, still do not know exactly what Mummy does at the hospital, and I am not sure how old they will be before I feel entirely comfortable explaining all. They assume, I imagine, that I save lives for a living.

That is, after all, the old medical paradigm. The dramatized doctors who stride across our television screens, swoop in, take command, deploy their skills and save the day. Stethoscopes in place of capes, but doctor-heroes all the same, prolonging life, denying death, playing God with impunity.

When I was a child myself, devoted to my physician father, I came to glimpse through him a different, quieter style of doctoring in which medicine perhaps achieved less yet was kinder and more humane. I learned from his inexhaustible tales that even when a patient’s fate seems hopeless, a doctor, if they care, through their basic humanity, can always make things more bearable, and that this was something to emulate. The lesson must have lodged in my brain.

Kindness, courage, love, tenderness—these are the qualities that so often saturate a person’s last days.

Two decades later, upon belatedly qualifying as a doctor myself, I would discover that a frenetic, overstretched hospital environment threatened to stamp out of medicine the very things that had made me most proud of my father—his unassuming attention to his patients, an innate and profound love of people. Exhausted doctors swiftly mutate into burned-out ones who wearily go through the motions of healing.

Perversely, the one part of the hospital that allowed me to flourish as a doctor was the ward most steeped in fear and taboo: the inpatient palliative care unit. If I told you that my work there today is more uplifting, more full of meaning, than any other form of medicine I could imagine practicing, you might think too much time in the hospice had addled my brain. But what dominates palliative medicine is not the proximity to death, but the best bits of living.

Kindness, courage, love, tenderness—these are the qualities that so often saturate a person’s last days. It can be chaotic, messy, almost violent with grief, but I am surrounded at work by human beings at their most remarkable, unable to retreat from the fact and the ache of our impermanence, yet getting on with living and loving all the same.

One way or another, I have circled death and dying for half a lifetime. Like most of us, blithely pretending our days are not numbered, I have had my share of close shaves. Narrowly escaping a terrorist nail bomb, crawling out of the wreckage of a car on black ice, even fleeing bullets from Congolese child soldiers. Then, in choosing to become a doctor, I elected to attend more closely to death—and to the inevitable grief it unleashes.

Finally, upon specializing in palliative medicine, I learned that dying, up close, is not what you imagine. For the dying are living, like everyone else. It is the essence of living—beautiful, bittersweet, fragile life—that really matters in a hospice. You would be surprised by what we get up to.

__________________________________

From Dear Life by Rachel Clarke. Copyright © 2020 by the author and reprinted by permission of St. Martin’s Publishing Group.

Rachel Clarke

Rachel Clarke is a British palliative care doctor. A former television journalist, she retrained as a doctor and is now well known in the UK as a commentator and advocate for the best possible standards for patients, doctors, nurses and other carers. Her specialism allows her to put into practice her passionate belief in helping patients at the end of life to experience the best possible quality of life. Clarke lives in Oxford with her husband and two children.