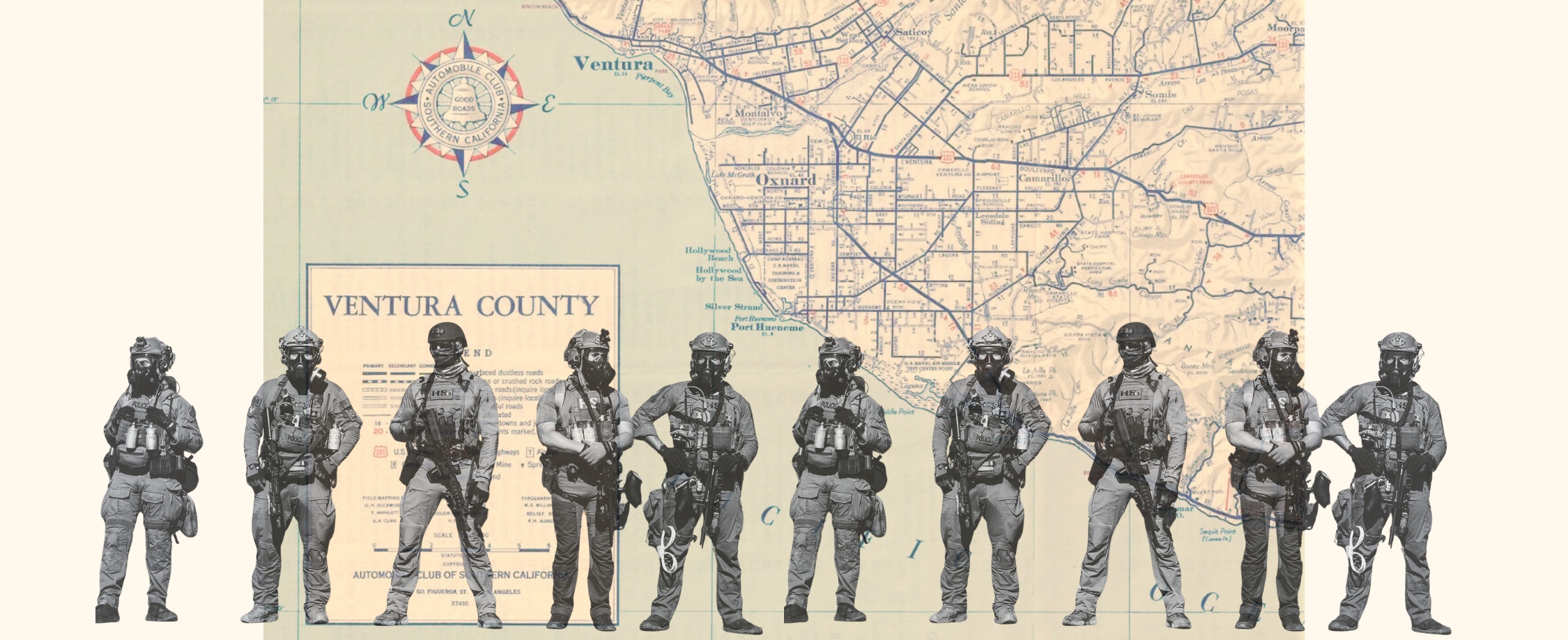

What ICE’s Assault on Ventura County, California Means for the Rest of America

Steven W. Thrasher on the Brutal Raids by Trump’s Ever-Growing Masked Army

“Mom is gone. They took her away.”

These are the words of an 8-year-old Mexican-American girl I will call Maria, in my hometown of Oxnard, California. She spoke them to her summer school teachers this past week, one of whom is a friend of mine.

Maria’s mother was disappeared by ICE, the worst fear for many families in Ventura County, which emerged on the world stage recently as an ICE raid on the Glass House cannabis farm in Camarillo resulted in the death of farmer Jaime Alanís, the kidnapping of California State University Channel Island professor Jonathan Caravello, and the disappearance and presumed deportation of at least 200 farmers.

Fortunately for Maria, her two tias picked her up the day her mom was kidnapped, and “they took me to Toppers, and I got to eat the ice cream cookie!” Her teacher—I’ll call her Miss Garvin—told me how Maria had never had the ice cream cookie at Toppers before, and that she was trying to hold onto this treat. It seemed as if the adults in Maria’s life were letting her have anything special to distract her—because they did not know when, or even if, she was going to see her mother again.

Miss Garvin told me that “it was a shitshow of a day” as she kept Maria in her line of vision throughout the breakfast and lunch periods.

“It broke my heart,” she told me, to see this normally vivacious girl sitting shell shocked and mute around her friends.

Like Maria, I hail from Ventura County, and am a product of its Title 1 schools. From six to nine years old, I was bused through Oxnard’s bountiful agricultural fields and (literally) across the railroad tracks to the La Colonia neighborhood, where Ramona School educated students like me pretty well despite how economically neglected we were. (I still remember how few streetlights there were when we were bused before dawn, and that there were chickens running through the pot-holed streets just outside our school’s windows).

Ventura County is playing a crucial role in the attempt to stop fascism right now, for the good people of Ventura, Camarillo, and Oxnard are not taking ICE raids without a fight.

Like Maria, my biological mother disappeared when I was about her age, though not because she was kidnapped. (She just disappeared for three years while no one, including the private detective my dad and stepmother hired, could find any trace of her beyond an abandoned car.) Like Maria, my survival depended on the care of an Oxnard teacher like Miss Garvin.

Like Maria, I am also a product of Ventura County’s fields, which gave me a place to play, taught me about labor politics, employed the vast majority of my classmates’ parents, and fed me.

But you, wherever you are reading this, you are likely a product of Ventura County’s fields, too—especially if you’ve ever eaten a strawberry. Strawberries are harvested with backbreaking work usually done by undocumented migrant farmers. Oxnard is the largest producer of strawberries in California and is known as the “strawberry capital of the world.” Our 93,000 acres of farmland provides California, the United States, and even other countries not just various berries but avocados, mushrooms, corn, citrus, and even marijuana.

And you are also a product of Ventura County because the Oxnard plain is a hot bed of radical politics. Historically, Ventura County has played a pivotal role in the evolution of labor organizing, as Cesar Chavez lived there for a time and had a strong base of operations during the rise of United Farm Workers.

Just as importantly, Ventura County is playing a crucial role in the attempt to stop fascism right now, for the good people of Ventura, Camarillo, and Oxnard are not taking ICE raids without a fight. Since Trump came back into office, groups like VC Defensa and the 805 Immigration Coalition have been training volunteers to patrol for ICE agents. And when they’re spotted, a call goes out for community members to show up—and people from all walks of life (students, citizens, senior citizens) do.

That’s what happened on July 11: a scout patrol spotted ICE agents and tipped off hundreds of people who showed up at the Glass House Farm to bear witness to the ICE raid.

The terror of ICE has pushed immigrant families in Ventura County to their deaths in ways fast and slow.

That initial patrol consisted of Cal State Prof. Caravello and his friend, colleague, and former student, Angelmarie Taylor. Taylor told me she had taken many classes with Prof. Caravello, including “Ethics for a Free World,” a social justice philosophy class meant to teach students “to understand the political world around us.”

“He was the rare professor who really cared about students,” Taylor told me. “He would ask about us after class, one on one, human to human.”

Ironically, Prof. Caravello “taught de-escalation workshops,” she added, and was often the police liaison at CSUCI protests who negotiated between the cops and the students to make sure things didn’t turn violent. But on July 11, Prof. Caravello did not get to use his de-escalation skills. Instead, ICE lobbed dangerous tear gas canisters at the peaceful protesters. As a video I reviewed shows, one agent even kicked a fuming canister under someone’s wheelchair—and then, according to eyewitnesses, as Prof. Caravello was trying to help the person in the wheelchair avoid the poison gas, he was tackled, abducted, and taken away.

Taylor was Caravello’s local emergency contact that day, and spent 48 frantic hours trying to find where he had been kidnapped.

I’ve had a lot of trouble sleeping this week as I have thought about both little Maria missing her kidnapped mother, and about kidnapped Prof. Caravello cut off from his family in his cell somewhere—and about how the fate of America rests upon abolishing this collective, familial, intergenerational punishment of human freedom.

And this is also why you are a product of Ventura County, too—and why your fate depends on what happens there.

If Ventura County falls, we are all going to fall. And the way people there have been treated as threats for interfering with the duties of police—a criminal charge I briefly faced as a professor under similar circumstances as the CSUCI professor—reveal the terror hundreds of millions could face if ICE does, in fact, get a six-fold increase in funding and becomes a bigger internal force than most countries’ militaries.

*

Even without the threat of ICE, farming has long been identified as one of the most dangerous jobs in America. Given that “more people die while farming than while serving as police officers, firefighters or other emergency responders,” the idea that ICE officers fear for their lives while approaching farmers is absurd.

But the terror of ICE has pushed immigrant families in Ventura County to their deaths in ways fast and slow.

In a case that should be considered a homicide, this was most tragically clear when the fear of ICE chased 57-year-old Jaime Alanís off a 30-foot building at the Glass House Farm raid. He was the sole provider for his family in Mexico.

At the same time, forms of social, nutritional, financial, spiritual and slow death are also being wreaked by ICE on migrant communities.

Oxnard is full of fun, colorful Mexican grocery stores. Miss Garvin, the teacher, reminded me that “On the weekends, they were packed. Packed. But if you go right now, it’s half the foot traffic.”

“You’re terrified of ICE,” she continued, putting herself in the shoes of her students’ parents. “You can’t go to work. Most of these parents have at least two jobs, each. But they’re scared to go to the grocery store.”

There are going to be acres and acres of food that’s not going to get picked, that will sit there and rot, because there’s not going to be anyone to come pick it.

While her school district “has been offering workshops so that every family knows they don’t have to open the door” if anyone comes knocking without a warrant, that doesn’t address a crucial question: What happens when you fear you an encounter with ICE anywhere beyond your door at any time?

For people who have reasonable suspicion they may be picked up, the only way to avoid being kidnapped is to, in essence, remain under house arrest.

By June, my friend told me, things had gotten so hot with ICE in Oxnard that for her teaching colleagues, “Most of us have had at least one student whose parents did not send kids to school. I had three kids who didn’t finish the year.”

“It hurts your heart,” she said. “They’re good families. Education is really important to them. And for them to not be able to be there? And for them to not be able to finish the year?” Her class had recently finished standardized tests, and “they’re missing the end-of-year activities: field days. Soccer games. And nope, they don’t get to enjoy any of it. They don’t get to reap any of the benefits of their hard work!”

Things have gotten so bad, my teacher friend tells me, that a comic book shop in our hometown has a very different mission now than just selling the latest DC or Marvel serials: It has largely been turned into a makeshift food pantry. The store takes in donations of diapers and baby formula, where people who are the least afraid of being picked up by ICE in their home can go to get donations for those who are unable to earn a living or get to a store.

“If you think about a place like Palestine,” my friend said, “they have zero access to food, because nothing is being allowed to come in,” and so people are going hungry, while the US-Israeli blockade keeps it out. But back in the United States, the Trump administration will soon be incinerating 500 tons of emergency food aid; meanwhile, in Ventura County, Miss Garvin observed, there is no shortage of food, but the farmworkers “no longer have access to the actual food they’ve picked, because we are so far from treating them like human beings. And the irony is that there are going to be acres and acres of food that’s not going to get picked, that will sit there and rot, because there’s not going to be anyone to come pick it.”

*

By the time ICE had concluded its nasty business at Glass House Farm, their raid disappeared more than 200 people. Because they were undocumented, who, exactly, was taken into custody—and where they are held or headed—is not known.

But the most unusual abduction for a farm raid—not because he was more important, but because he was a US citizen with a PhD—was professor Jonathan Caravello, a philosopher and longtime labor organizer who worked at the nearby Cal State University Channel Islands.

The night before the raid, out of concern for many of his students who were undocumented, Prof. Caravello addressed the Camarillo City Council about the uptick of raids, and he linked the problem from the strawberry fields of Oxnard to the blown up fields of Palestine:

Many call these neighbors “illegal,” but let’s talk for a second about what’s really illegal. When the US bombs civilian nuclear sites, like they did in Iran late last month, it’s illegal. When the US provides weapons to an apartheid state to fuel a genocide, like it continues to do in Palestine, it is illegal. …And today, armed, masked thugs are bending the knee to just follow orders to kidnap, imprison and deport our neighbors to countries that we destabilize, that we have under the thumb of our political and economic domination, whose soil we destroy with pesticide-ridden bananas, whose leaders we depose and whose people our media continue to dehumanize.

Who are we to constrict the movement of our fellow human beings? Who are we to judge how people choose to live? ICE is not welcome here, just like the US is not welcome in other countries. And you, our elected officials, should swear them off, if not in policy, then in spirit, to at the very least pay back your undocumented community members for picking your fucking strawberries. No one is illegal. Power to the people.

The next day, Prof. Caravello was patrolling near the Cal State campus with Angelmarie Taylor when they spotted ICE agents on the hunt. They put out an immediate call on their mutual aid networks. When they arrived on site, about ten people were there.

Throughout the day, Taylor estimated, more than 1,000 protesters came through.

“Prof. Caravello and I have been doing this kind of work for years,” she told me. She said that they go to observe but not to physically intervene between protesters and police, and that Prof. Carvello is always “trying to de-escalate situations.”

But this day was different: they had “never seen anything like that before.” ICE wasn’t “giving us any orders for dispersal, they were just using tear gas, using OC spray,” which were making people sick.

(Tear-gas canisters are no joke, as I can personally attest, having been gassed more times than I can remember covering protests. They travel at high speeds, can make people go blind, spew a gas which is so poisonous it is illegal to use in war under the Geneva Convention, and can cause serious burns, brain damage or death.)

Prof. Caravello was near someone in a wheelchair as ICE agents shot tear gas canisters into the crowd. As the Coyote Chronicle reported, “one canister land[ed] under the wheelchair of a legally present observer who struggled to breathe or move. Dr. Caravello rushed to help the bystander and was immediately tackled by agents, thrown into an unmarked vehicle, and taken to an undisclosed location.”

ICE’s stance is that its agents can snatch anyone, anywhere, for any reason.

For Angelmarie Taylor, the experience of seeing her friend and former professor tackled was “extremely traumatic.” She and her comrades spent the next 48 hours trying to find out where he was, making calls and visits to every detention center and hospital in the region. Taylor said that they had contacted the facility in neighboring Los Angeles County from which Prof. Caravello was eventually released, but that they had “straight up lied to us” and said that he wasn’t there.

The press then played a role in creating the false impression that the protesters were causing violence, not the government agents, by claiming that Caravello was the one to throw a tear gas canister—at ICE! Quickly, the headlines from the CBS and ABC affiliates in Los Angeles (“Cal State Channel Islands professor threw tear gas canister at police, US Attorney says,” “CSU Channel Islands Professor arrested over tear gas incident at Camarillo immigration raid”) were indistinguishable from those of Campus Reform or Fox News (“Cal State prof arrested, accused of assaulting agents during cannabis farm raid,” “Leftist Professor Arrested for Allegedly Hurling Tear Gas At Feds During ICE Raid”).

After several days, during which his friends and family did not know where he was, Prof. Caravello was released. But like Latino families in Ventura County who are too frightened to leave their houses, he is under a kind of California house arrest. Taylor told me Caravello can leave his home, but he’s surrendered his passport, is wearing an ankle monitor which tracks all of his movements, and he’s barred from leaving California to visit his family in Arizona.

Prof. Caravello is also charged under United States Penal Code 18 USC 111 and stands accused of “assaulting, resisting, or impeding certain officers or employees.”

This is the same bullshit argument regurgitated by the CBS affiliate about a viral video which showed ICE agents trying to arrest a man inside an Ontario, California surgical center last week. The news anchors say, that “ICE agents were trying to make an arrest when they claim medical staff assaulted them.” While the man in the video was not necessarily a patient at that time—he seemed to be a landscaper working right outside—he ran inside begging for help. And the staff, who said they “took an oath” to protect people, tried to keep ICE from harming him.

But ICE’s stance is that its agents can snatch anyone, anywhere, for any reason—so it can press charges against the surgical staff for interfering in its broad, nearly limitless mission.

And this is where it gets scary for you, for me, for all of us who ever stand up: if convicted of United States Penal Code 18 USC 111, the maximum penalty is 20 years.

So, as the ICE budget grows exponentially, and immigration enforcement is woven into every element of US society…

Imagine being a doctor, nurse or medical assistant, and you are prepping your patient for surgery, and you have an intravenous line into them—and then stormtroopers barge in, threatening the health of your patient.

When ICE is creating hunger, hostages and house arrests, who is interrupting whose duties here?

If you try to make sure the patient you’ve sworn a hippocratic oath to protect isn’t harmed, you can be sent to prison for 20 years for interfering with the duties of an officer under United States Penal Code 18 USC 111.

Or, imagine that you’re a minister, imam or rabbi, and your life’s calling is to care for a congregation—and then stormtroopers barge into your house of worship, threatening to separate a mother and a child in your care.

If you try to make sure the family you’ve sworn an oath to your God to protect is not separated, you can be prosecuted for interfering with the duties of an officer under United States Penal Code 18 USC 111.

Or, imagine you’re a professor, and you see a rogue agent throw a gaseous bomb under someone’s wheelchair, and you toss the hot bomb away from the choking disabled person in the wheelchair, you can be prosecuted for interfering with the duties of an officer under United States Penal Code 18 USC 111.

Now imagine that you’re my friend Miss Garvin, or her principal, and you’re looking out for little Maria and her friends.

Miss Garvin told me that as soon as there is any report of ICE being near their school, their principal is “walking the perimeter of the school looking out for them, getting on the walkie-talkie and telling us, ‘No, they’re not coming here, they’re not stepping one foot on our campus.’” Then, all the teachers fan out as school lets out to protect their kids until they are handed off, “because we need all parents and students to feel safe that nothing bad is going to happen to them while they leave the school.”

If ICE were to show up, and you were any of those Oxnard educators and you fulfilled your duty to protect the families you serve, you, too, could be prosecuted and sentenced to 20 years in prison under United States Penal Code 18 USC 111.

But when ICE is creating hunger, hostages and house arrests, who is interrupting whose duties here?

Are medical staff, professors and clergy preventing the police from their duties, or are police preventing us from caring for each other—and for extending care to those in wheelchairs who are gassed, or to farmers who are running for their lives, or little 8-year-old Maria whose mom has been taken away?

ICE should be abolished. But the carework which policing interferes with must be protected at all costs.

Nothing less than the reasons for our very lives depends upon this.

Steven W. Thrasher

Steven W. Thrasher, PhD, CPT, a journalist, social epidemiologist, and cultural critic, holds the Daniel Renberg chair at the Medill School of Journalism, and is on the faculty of Northwestern University’s Institute of Sexual and Gender Minority Health and Wellbeing. A former writer for the Village Voice, Scientific American and the Guardian, Thrasher is the author of the critically acclaimed book The Viral Underclass: The Human Toll When Inequality and Disease Collide. [Photo by C.S. Muncy]