What Happens When You Read Your Mother’s X-Rated Novel

Kate Feiffer on Female-Authored Erotica As a Form of Social Critique

A few years ago, a writer friend asked me if there was a specific book that I considered to be my literary Waterloo. Was there a book I had hoped to conquer but hadn’t been able to? While I have long planned to read Stendhal’s The Red and The Black and Dickens’ Bleak House, the book that immediately came to mind was short, breezy, and X-rated.

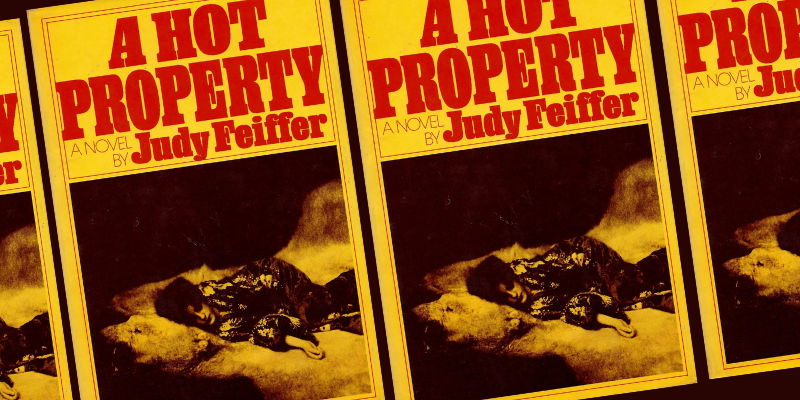

A Hot Property is a mere 171 pages and was written by mother, Judy Feiffer. The book was published in 1973, when I was a shy nine-year-old figuring out how to handle my combative parents who had recently split up. A Hot Property was called “funny” and “raunchy” by New York Times book reviewer Anatole Broyard, who also noted that my mother had found new and inventive ways to write about sex: “Mrs. Feiffer manages, even at this late date, to introduce a few new wrinkles into the subject. To genital, oral and anal variations, she has added nasal.”

My mother was writing about the mores of her time. She wasn’t endorsing, she was reflecting. Perhaps she was even skewering.

I didn’t read this or any other review, nor did I ever crack open the book, when I was a child. I had assumed my mother had written a novel about real estate—after all the title was A Hot Property—until my high school boyfriend plucked it off the shelf one day and started reading select passages aloud. Passages like, “Ubango’s nose was grinding deeper. It pushed upward like a mole burrowing toward the sun. A moist, mucus fluid drained down her leg.”

After my father left, my mother was anxious about money. While my father was providing child support, she clearly found the settlement they had agreed on to be insufficient. It was the early 1970’s and Jacqueline Susann had seduced millions of readers with her New York Times bestselling books Valley of the Dolls and The Love Machine. My mother must have thought she could be the next Jacqueline Susann. After all they were both smart, Jewish born beauties who had a way with words.

And my mother was an avid reader with a seductive admiration for writers. In her twenties, while working as a photographer, she took author photos of Aldous Huxley, Alberto Moravia, and Meyer Levin. A portrait she took of Norman Mailer wearing a skipper’s hat was used for the cover of his controversial collection of essays, stories, and verse Advertisements for Myself. In her early thirties she married my father, Jules Feiffer, who was fast making a name for himself as a cartoonist and satirist. They had literary friends and well-known writers sometimes came for dinner. I’ve been told that it was at one of their dinner parties that Bernard Malamud cornered my mother in the kitchen and informed her that my father was having an affair with a beautiful young painter. My parents split up shortly after that.

I realize she was bravely chronicling, if not commenting, on how a certain set of self-involved literary lions behaved.

My mother had recently died when my friend asked me this question about my literary Waterloo. It was time. I was ready to read A Hot Property. I would approach the book with the understanding that my mother had written it as a single woman trying to support herself and her daughter. There weren’t many high paying jobs for women in the 1970’s, and she saw an opportunity to make some money. She wasn’t trying to embarrass me; she wrote it because she wanted to be independent and financially responsible.

By the time I got to page fifteen, I was screaming, “No! Mom, No!”

By page fifteen, readers have been introduced to a bookish high school girl named Esther who is eager to start experiencing life. Her father is a literary agent, and she has reached out to one of his clients, a frustrated novelist who hasn’t received the acclaim he believes is his due. His wife is out of town and he invites Esther over. He even tells her he’ll pay for her taxi. And then on page fifteen, “He pulled down her Fruit of the Loom underpants and turned her over.” On page fifteen, “He burst into her like a grenade and she screamed in panic and pain.”

But wait. In the early 1970’s men in a certain places and professions could sleep with high school students with impunity. Woody Allen proved that with his film Manhattan, in which a young Mariel Hemingway, whose character in the film was going to the same high school I attended, is dating a 42-year-old comedy writer played by Woody Allen. And that film came out in 1979, six years after my mother’s book was published. My mother was writing about the mores of her time. She wasn’t endorsing, she was reflecting. Perhaps she was even skewering.

It’s challenging to forgive or even sit comfortably with what we now judge as unconscionable behavior—even when it’s fictional—by allowing for the context of a different time. As I continued reading A Hot Property, there were many more bouts of, “No! Mom, No!” I wondered how could she have written this. What was she thinking? What was she doing? But now, as I write this, I realize she was bravely chronicling, if not commenting, on how a certain set of self-involved literary lions behaved.

The book didn’t become a best seller, perhaps because of the squirm-worthy nose-orgasmy scene, perhaps because it was misunderstood, perhaps because it was something other than a conventional pot-boiler. Erica Jong’s Fear of Flying was also published in 1973. It’s possible the country couldn’t handle both the “zipless fuck” and the “volcanic sneeze” from two female writers in the same year.

My mother later tried again with her novel Flame, and a young-adult novel titled Love Crazy, which was about two best friends who try to seduce each other’s fathers. I read both those books when they were published. Neither was easy for me to stomach, but I got through them. The final book my mother wrote was titled My Passionate Mother. It was about a woman who had two great lovers in her life, but because my mother liked to push boundaries, one of the woman’s lovers also falls into the arms of (No! Mom, No!) her daughter.

My passionate mother, indeed.

__________________________________

Morning Pages by Kate Feiffer is available from Regalo Press.

Kate Feiffer

Kate Feiffer is the author of eleven books for children. Morning Pages, her first novel for adults will be published by Regalo Press in May.