What Fiction Writing Shares With Psychotherapy

Emily Howes Considers the Similarities Between Two Therapeutic Practices

“Creation and healing are the same energy; they transform pain rather than being destroyed by it.”

–Shaun McNiff

*Article continues after advertisement

I have a curious double professional identity. I am both a novelist and a therapist; both a teller of tales, and a listener to them. I spend my days in my own imagination or settling into the deepest corners of the imaginations of others. People sometimes wonder, usually at literary events, how I manage the two. Am I a novel-writing therapist or a therapy-offering novelist?

They seem so different, people say. This, I think, is Freud’s fault. Determined to fit his ideas into a medical model, he strained his patients’ experiences into scientific certainties, into ‘pathogenesis’ and ‘pathologies’ to acquire a ‘cure’ through ‘analytic results’. The term ‘patient,’ often discarded by contemporary therapists, speaks for itself. Even now, TikTok therapists hand out diagnoses like sweets, identifying attachment styles as though the ephemeral nature of experience can be drawn up and labelled like a diagram. We deal in psychopathologies, in unconscious motivators, in dysfunctions and disorders.

Surely this is a very different kind of work to the fanciful, artistic endeavor of the historical novelist. But science, really, is a story too. A story about confidence. A story with a happy ending, in which everything frightening can be contained by certainties. Life itself is an uncertain endeavor. We create ourselves, and creativity, I would argue, has very little to do with scientific certainty.

Reader and writer, therapist and client, come together to conjure something in a mysterious symbiosis.In the early 1950s, my grandmother was taken into a mental asylum in South Wales, suffering, apparently, from postnatal depression. She never came out. I didn’t know her; at four years old my mother was taken in by family members, and ultimately adopted by them.

Later my mother told me that she has only two memories of the woman who gave birth to her. Shortly after admission, her mother came to her new home on a day visit. Pale and bloated from the effects of electroshock treatment, this woman bore no relation to the mother she remembered, an experience so frightening that she ran instantly and hid under the bed. She recalls being dragged out and made to kiss her mother, and the terror of being forced to do so. In another memory, my mother, now a teenager, refused to go into the asylum, and stood instead in the carpark, looking up at the broad building. A face at a window; unmistakeably her mother’s. Unbearable to look at.

It was a story long buried. My mother grew up in an atmosphere soaked in fear and shame, unable to voice anything about what was happening to her. There were playground taunts. The loony bin. The nuthouse. And, worse, an unspoken fear that she, too, would go mad; that this was something in her blood, a thought that haunted her as a child. She made the decision not to tell me the story, or only to tell me part of it. There was no mention of mental illness, only a grandmother who “wasn’t very well.” Yet when I found out the truth as an adult, I felt as though I had always known it.

‘Psychopathology’ is a term that would certainly have struck awe into my grandmother, and those around her. Yet in direct translation from the Greek, ‘psychopathology’ means simply ‘knowledge of the suffering of the soul.’ The suffering of the soul is the stuff of much more than science would have us allow, within its narrow confines, and its reassuringly formal concepts of ‘treatment’ and ‘cure;’ its white-coated authority.

My work as a psychotherapist reveals the complex, often mysterious intertwining of contributing factors to mental struggles. One of the most vicious, in my experience, is fear. My role is, in part, to normalize; to say, “it’s ok if you feel this way.” It is also to allow words stifled by fear for too long to emerge, falteringly, into the air.

I see people with anxiety, with an indefinable sadness, with a sense of a life half-lived. I see people who are suffering, but don’t know why. I see people who cannot find themselves, who cannot understand who they are or how they came to be this way or find the words to express long buried memories that have been too painful to face. It is a place to let wounds breathe and heal. The questions they are asking of themselves are the questions the characters in my novel also ask, whether they know it or not. Why am I here? Where do I find myself? What do I want?

Both therapy and writing are explorations of experience, by their nature both creative and dyadic. In therapy, we travel softly together into the client’s mind, into their imagination, their emotion, their memory. As a writer, I ask the reader to travel to the same places. We go via fictional characters, via something that feels invented, but in the end, it is the reader who creates the world I provide the words for from their own experience.

Therapy and writing are explorations of experience, by their nature both creative and dyadic.Reader and writer, therapist and client, come together to conjure something in a mysterious symbiosis that will help make sense of the experience of being alive. We can uncover stories we have told about ourselves that we didn’t even know were there.

We can dismantle old narratives and form new ones. Through these delicate, chiasmatic relations with each other, we can find our selfhood reflected back to us, and find a way to make peace with hidden things by bringing them out into the light and acknowledging them as part of our narrative.

A client comes to me feeling ‘scattered.’ After his father died during his teens, he went into a self-destructive spiral, drinking heavily. It becomes clear, as we work together, that my client has cut this part of himself adrift. He refers to his teenage self as ‘him,’ rather than as ‘I.’ He can’t find any forgiveness in himself for how he behaved, because he can’t face it. In our first session, he looks at me, unsure of where to begin, and when I ask what is happening for him, he says he feels lost, and can’t piece the narrative of himself together.

Over the course of our therapy together, he begins to look at these dark, unspeakable parts of himself. As he begins to acknowledge and give voice to things left unsaid, his understanding of himself now grows richer, more shaded, and, crucially, less paralyzed by fear. This feels, to me, like a process of writing. The point of writing, after all, has very little to do with product, or the journey to publication, and a huge amount to do with self-expression.

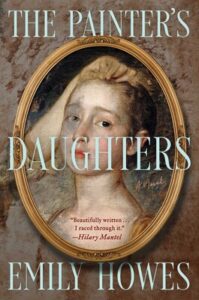

Writing became a kind of therapy for me in bringing to life my own family history, and helping me to uncover parts of it I had not known were still with me. My debut novel The Painter’s Daughters is the story of Peggy and Molly Gainsborough, the two daughters of the celebrated 18th century portrait painter Thomas Gainsborough. Molly, the elder of the two, begins as a child to suffer from the bouts of mental instability that will dominate her life. Peggy, the younger, knows instinctively that she must hide the signs of Molly’s illness from those around them. As the girls grow into adulthood, Peggy finds herself forced to ask how much she will be prepared to sacrifice in order to protect her sister.

To my telling of this beautiful story of sisterly love, I bring my own inherited sense of the panic and confusion through which my mother lived. I find words to shape something of that experience, and of the intangible way in which I carry it two generations later. Through that retelling, I myself find a kind of healing.

__________________________________

The Painter’s Daughters by Emily Howes is available from Simon & Schuster.