Los Angeles. The J. Paul Getty Museum. Present day. The illuminated manuscript pages dwelled in the modern cabinet in the sterile storage room. A visage emerged from the carpet of gold on one of the parchment sheets. He had been restless ever since the great rupture. He stole a glance upward.

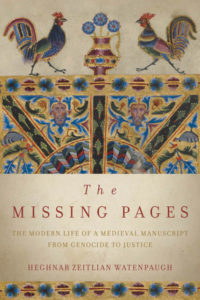

Some things had not changed. Above him the roosters strode confidently toward a jeweled vase. To his left his twin visage kept watch. Beneath them an arch opened up like a fan. The partridges and blue birds hidden in the gold leaf still pecked at tendrils. All this rested on three columns of painted porphyry and patterned gold. The column capitals, the blue ox heads, bore the weight, docile as ever. Beyond the frame birds alighted on the pomegranate trees and the outlandish plants Toros had devised. The visage could still feel the painter’s breath as he labored over every detail, holding his delicate brushes. The letters Toros had inscribed beneath the arch stood at attention at their appointed places in a grid outlined in gold. The visage could see all the way down to the base of the columns. Tiny red dots sprinkled along the base resonated with the red of the pomegranates, the roosters’ combs and wattles, even the visage’s own headgear.

Other things had changed, however. The visage remembered that in the beginning he had lived across from another page, a near-echo of his own, with similar roosters, oxen, pomegranate trees, the fanlike arch, even the red dots. His page and the original echo page featured myriad differences, too, that the visage delighted in finding over and over again. Since the great rupture, that echo page had moved away. The visage shared a bifolium with another page instead. Even though it too had an arch, a grid of letters, and even the same color scheme, its differences were jarring. Its trees were palms bearing owls, its partridges pecked at a silver vase, its carpet of gold bore distinct ornaments, its column capitals were twin birds, and its grid of letters was denser. It was not his echo. It was never meant to be seen across from him.

The visage resumed his silent vigil. He had survived the great rupture, but would he ever find his echo again?

*

Consider the Canon Tables of the Zeytun Gospels, preserved today at the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles. You are looking at four sheets of parchment. Each sheet of parchment is folded down the middle, turning into two connected leaves. In the art of bookmaking, a folded sheet is called a bifolium and yields four sides: four folios. Each folio measures 26.5 by 19 centimeters. The Canon Tables consists of a total of sixteen folios. Eight of the folios bear illuminations, while their eight backs are left blank. These folded sheets of parchment were once nested together in a gathering and bound with other gatherings of folded parchment.

In the resultant book, the pages appeared in a carefully ordered sequence. As you opened the book and looked at the Canon Tables, you saw the illuminated folios as matched sets, as four pairs of pages facing one another. The facing pages echoed each other’s decoration. As your eye traveled from one page to the other, you would notice their similarities as well as subtle differences, not unlike a refined “Spot the Difference” puzzle. Between each illuminated pair the blank folios allowed you to pause and cleanse your palate before turning to the next meticulously crafted pair of images. The makers of this artwork of great luxury used the most lavish materials, and they could afford to have only one side of a parchment page painted.

The illuminated pages feature decorated architectural frames. The frames shelter golden grids that contain series of letters written in the Armenian alphabet in bolorgir, a lowercase script. Around the frames many species of birds frolic; some hold fish in their beaks, and others drink from vessels or nibble at stylized plants and flowers. Within the frames you discern more birds and even human faces, nestled among ornamental fields in brilliant colors. The facing pairs of the Canon Tables feature the same layouts, yet each page looks unique. The painter Toros Roslin, working in 1256 in the Kingdom of Cilicia, unified them in design yet created subtle distinctions. He distilled the essence of medieval visual harmony into eight glorious painted pages.

This crease marks the moment when the work became a fragment; it is the trace of its loss.The letters within the frames represent numbers. The grids of letters are thus numerical tables of a specific kind. The pages at the Getty depict canon tables—concordance lists of passages that relate the same events in two or more of the four Gospels. Designed by Eusebius of Caesarea in the 300s, by the early Middle Ages canon tables almost always preceded the Gospels and usually featured columns of numbers assembled within painted architectural structures. The Canon Tables now at the Getty was once part of a manuscript copy of the four narratives of Christ’s life by Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John that make up the Christian New Testament. The manuscript is known as the Zeytun Gospels after the remote mountain town where it was once kept and revered for its mystical powers of blessing and protection. When the people of Zeytun were exiled from their homes and exterminated, the manuscript too was taken away and broken into fragments.

The gathering of illuminated Canon Tables that is now in Los Angeles was detached from the mother manuscript of the Zeytun Gospels. No longer part of a book, it now appears as component parts: four sheets of parchment, folded in the middle. You can still see the small holes in the vertical fold at the center of each bifolium, where the threads that bound the manuscript together into a codex would once have been. Perhaps the Canon Tables came loose from the binding over time. Or perhaps someone cut the thread. In any event, somehow the pages bearing the Canon Tables were removed from the Zeytun Gospels.

Viewing the Canon Tables displayed at the museum, you will also notice another feature that does not readily lend itself to photography. A crease extends horizontally across the two connected pages. It seems that no amount of careful conservation will smooth it out. This crease tells you something about the life story of the Canon Tables. It was likely caused when the gathering was removed from the mother manuscript and folded up. This crease enables you to imagine how, at some point, unknown hands removed the Canon Tables from the mother manuscript, how they folded it, perhaps tucked it in a pocket or in the folds of a fabric belt like the ones men wore in the waning days of the Ottoman Empire, and took it away. The crease shows us that the work of art bears the imprint of the actions it endured, and of its separation from the mother manuscript. This crease marks the moment when the work became a fragment; it is the trace of its loss.

At that moment the holy manuscript cleaved into two. Each piece acquired a new possessor and embarked on a distinct journey. The mother manuscript followed a twisted path that eventually took it to the Republic of Armenia. The Canon Tables left the Mediterranean littoral, moved across the Atlantic Ocean, and decades later made landfall on the Pacific shore, in one of the world’s greatest and wealthiest museums. In Los Angeles, descendants of the community that once revered the Zeytun Gospels as a devotional object brought out only on special religious occasions can now view its detached Canon Tables on exhibition, displayed alongside other works of art in a museum hall, open to the public.

A fortuitous chain of circumstances brought the Canon Tables to Los Angeles. The Zeytun Gospels is a remnant of a medieval world that is lost forever. It is also the only medieval relic that has come down to us from the once-rich treasuries of Zeytun’s churches. It is among the rare manuscripts to survive the unprecedented assault on Armenian cultural heritage that was part of what we now know as the Armenian Genocide. For every manuscript that endured, many more were lost forever, intentionally destroyed, burned, recycled for other uses, abandoned, or left to decay.

*

Provenance and Power

In 1995, shortly after acquiring the Canon Tables, the Getty Museum introduced it to the public with the following brief provenance:

Catholicos Constantine I (1221–67); bound into a Gospel book in Kahramanmaras, Turkey; Nazareth Atamian; private collection, U.S.

In 2016, the Getty amended the provenance:

1256, Catholicos Konstandin I, died 1267; by 1923–1994, in the possession of the Atamian Family; 1994, acquired by The J. Paul Getty Museum; 2016, gift of the Catholicosate of the Great House of Cilicia, by agreement.

These terse lists condense the biography of the Canon Tables since the creation of the Zeytun Gospels in 1256. In the twenty-odd years between the two versions of the provenance, the Canon Tables entered the manuscripts collection at the Getty Museum, appeared in scholarly exhibitions, became the subject of a contentious lawsuit, and saw it resolved through a settlement. The Armenian Church stipulated the change in provenance as one of the conditions of the agreement; in turn, the Church donated the Canon Tables to the Getty. The changes in the provenance are telling, but its silences are telling as well.

Provenance is a highly specific type of record, a chronological list of the successive owners of a work of art, and the manner of its transfer among them. Provenance communicates the itineraries objects trace through space and time as they are sold, inherited, bartered, and transferred. Provenance can transform the significance and value of an object in varied ways. It can alter its meaning, impact, and visibility just as surely as it impacts its location, state of preservation, and documentation. When provenance lists are known for objects of great antiquity, they may tell us much about the historic development of taste, the relationship between the present and the past, realities of war and economic exigencies. Recently art historians have delved into provenance as a meaningful type of text, even as an “alternate history of art,” a window on to the social life of art since its creation.

Provenance often tells ordinary, perfectly legal stories of sale, purchase, or inheritance. The archives of auction houses record which artworks sold and which languished unwanted, the bidding wars that reveal the allure of a particular object, as well as the rise and fall of artists whose works are in demand at one point then utterly forgotten. Inventories of art collections disclose the movement of paintings and sculptures as they are inherited, bequeathed, gifted, or sold to pay debts. Sometimes the artworks themselves tell their own stories: successive owners place their stamp or monogram on a valued object or add a binding to a medieval manuscript or a new frame to a Baroque panel painting. All of these sources provide information about provenance but also about the contexts of each transfer of ownership, the human stories and historical circumstances.

When a new owner acquires an object, its provenance acquires an added item. Curators and scholars make changes in the official provenance of objects in museum collections when they discover new information or correct an error. Sometimes, however, changes in provenance are made in response to pressure from legal action or public opinion. Consider, for example, the first time the Getty Museum made public the provenance of the Canon Tables from the Zeytun Gospels, in 1995, shortly after acquisition. This brief list mentions the first owner, Catholicos Constantine, Nazaret Atamian, and the Getty. The list mentions no owners between the death of Constantine in 1267 and Nazaret Atamian’s acquisition of the Canon Tables almost seven centuries later.

In 2016 the Getty modified the Canon Tables’ provenance as part of its agreement with the Armenian Church. The new provenance includes additional information about the Canon Tables’ ownership history in the twentieth century, the period under contention in the lawsuit. Its careful wording stops short of attributing ownership to the Atamian family, with whom the Canon Tables remained between 1923 and 1994. The new provenance acknowledges in effect that the Canon Tables always belonged to the Church, even when it resided with the Atamians and when it was acquired by the Getty in 1994, until the Church gifted the Canon Tables to the Getty in 2016. In this case litigation and negotiation invited renewed attention to the artwork’s history and eventually led to a new provenance. In its concision the provenance reveals little of the great labor of scholarship and litigation that went into its production.

Art objects, especially those ancient and valued, often have convoluted lives. Their provenance is rarely seamless. Gaps appear when records go missing, research yields no information, or objects are excavated by accident or by looters and their findspot remains undocumented. Darkly, in some cases, provenance can also tell—or conceal—stories of theft, war, atrocity, colonialism, genocide, destruction, appropriation, or exploitation. Art objects with a fragmentary or sketchy provenance may have been the result of illegal excavation or looting. For instance, shadowy middlemen or unscrupulous owners may obscure less savory episodes of an object’s life, as when looters pilfered an antique bronze from an excavation site in Italy, or when acquisitive collectors forcibly seized a sacred object from a Native American community, or when a Nazi official usurped a painting from a Jewish art dealer.

Certain kinds of record-keeping can be acts of resistance, uncovering suppressed episodes of an object’s history.In addition to telling tales, or obfuscating others, provenance itself can become contested terrain. In recent years attorneys, activists, indigenous communities, and some governments challenged collectors and museum officials with renewed zeal on the provenance of certain objects. They brought restitution claims regarding pieces that had been stolen, seized, or illegally exported, violating laws and international norms. After much resistance, the art world responded by emphasizing transparency in the provenance of objects in museum collections, and the art market grew more cautious in the sale of artworks with incomplete or questionable provenance. Despite greater awareness of such problems, the contest between communities and powerful institutions over the control of cultural patrimony continues—as in the case of the Canon Tables. The struggle for restitution, repatriation, and the reunification of art or sacred objects with their communities, and the fraught questions this raises, is one of the central issues of 21st-century art history.

These contests throw into sharp relief the relationships of power that structure the circulation of art objects and underlie every transaction that provenance chronicles. During conflicts, when art is liable to be looted, record-keeping becomes an act of power that can serve the interests of the powerful rather than the rightful claims of ownership that it purports to present. Thus, meticulous record-keeping was part and parcel of the Nazis’ organized looting of Europe’s art during World War II. Provenance can be a record of added value and prestige but it can also serve to obliterate traces of violence and injustice. Conversely, certain kinds of record-keeping can be acts of resistance, uncovering suppressed episodes of an object’s history. The curator Rose Valland, who witnessed the Nazis’ mass looting of art from French national institutions as well as private French Jewish collections, famously kept a secret inventory of looted objects, risking her life. Her notes proved invaluable for the recovery of art after the war.

The Canon Tables’ provenance, written and rewritten, chronicles the life of an artwork. It also speaks of the people who created it, worshipped it, traded it, and in some cases took terrible risks to save it. Violence, exile, separation, and migration mark the Zeytun Gospels’ trajectory over the last century. The silences in its provenance also tell tales about unequal struggles, seemingly hopeless causes, resistance, resilience, and contestation. The story that the provenance of the Zeytun Gospels tells matches the modern history of Armenians.

*

The Armenian Genocide

The Armenian Genocide and its many afterlives shape modern Armenian history, just as they determine the fate of the Zeytun Gospels. The Ottoman government carried out the systematic extermination of its own Armenian community during the Great War. On April 24, 1915, the symbolic beginning of the genocide, the Ottoman police rounded up Armenian community notables, politicians, intellectuals, and businessmen in the imperial capital of Istanbul. Most of them were murdered after varying periods of detention in central Anatolia. Parallel to this “decapitation” of the community’s leaders, the Ottoman state initiated the uprooting and extermination of ordinary Armenians in provinces throughout the empire. Zeytun was among the first localities targeted in early April 1915.

The pattern repeated itself with few variations: authorities separated out the Armenians from the rest of the population and ordered them into internal exile with little warning. Gendarmes and military officials led the civilians on long death marches away from cities, only to massacre them outright or allow them to perish from attacks by looters or bandits or from exposure. Survivors endured renewed ordeals, pushed ever eastward into the Syrian desert, away from the prying eyes of urban communities, journalists, or diplomats. The gendarmes herded Armenians into ill-equipped concentration camps in the desert where disease, starvation, and attacks ravaged them. While the last survivors were still agonizing, back in their homes neighbors and others were looting their houses and businesses; the state was confiscating their property through special laws; and the desecration, destruction, and plunder of religious and cultural sites was meeting little opposition.

The active extermination phase of the Armenian Genocide concluded when the Allied Powers defeated the Ottomans. The empire gave way to new republics, like Turkey, or successor states under the sway of France, such as Syria and Lebanon, or of Great Britain, such as Iraq and Palestine. Yet there was no full reckoning for the Armenians. The Republic of Turkey adopted an official policy of denial. Leaders of the republic included unrepentant genocide perpetrators, while the economic elite derived their affluence in part through confiscated Armenian wealth. In addition to silencing the past, the Turkish state subjected the remaining Armenians and all non-Muslim minorities to discrimination and persecution, and condoned hate crimes against them, fostering a culture of impunity.

Decades after its founding, the Turkish state continued to confiscate Armenian property, including communal religious property. Denial, continued persecution, hatred, expropriation of wealth, destruction of cultural monuments, appropriation of cultural achievements: there has not been acknowledgment, let alone apology, atonement, or reparation to any degree and any kind, even the most minimal, by state institutions. Indeed, genocide does not only consist in active killing but also extends to persecution, oppression, and dispossession, both open and clandestine, to the prevention of a group from the free practice of their language and religion, and to the creation of conditions that make it impossible for a community to continue to exist physically, religiously, and culturally. From this perspective, the Armenian Genocide is not only unacknowledged and denied; it persists into the present.

__________________________________

From The Missing Pages. Used with permission of Stanford University Press. Copyright © 2019 by Heghnar Zeitlian Watenpaugh.