What Does It Mean to Write Escapist Literature?

Caroline Carlson on Children’s Books and Escape Artistry

A few times over the course of my life, I’ve had to leave the world for a while.

One of those unplanned departures started with a phone call—you know the kind. The kind from a doctor’s office, the kind you’re hoping not to get in the early stages of a long-wanted pregnancy. There were some concerning indications on the ultrasound, the midwife explained. The pregnancy would likely end in miscarriage. Then again, it might not. “It’s an unusual condition,” the midwife said before offering me the three least helpful words in the English language: “Don’t Google it.”

I Googled it. Of course I did! Then I got into bed and stayed there for about two weeks, most of which I can’t truthfully remember. I don’t think I ate much; I know I cried plenty. I kept Googling that condition I wasn’t supposed to Google, typing it into the search box like it was some kind of magic spell for warding off disaster. I calculated probabilities. I slept, and woke up, and resented being awake. I became briefly obsessed with the Iditarod. I thought of everyone in the world suffering from losses more unbearable than mine, as if adding guilt to my sadness would somehow improve its quality. My husband convinced me to go see a movie, but I couldn’t understand the plot. I was supposed to be writing a book, but I couldn’t write.

I could still read, and once I discovered that I could, it was all I did. I began with Feeling Sorry for Celia, the young adult novel by Jaclyn Moriarty I’d read a half-dozen times before. The characters were Australian private-school teenagers, and their concerns—friendship dramas, mysterious crushes, pen-pal projects—were completely absorbing, often very funny, and blissfully different from my own.

I slept, and woke up, and read books, and discovered I could bear the world a little better.Best of all, the book was the first in a series of four, which meant that I could live in the Sydney suburbs of Moriarty’s endlessly inventive imagination for a good long while. During those weeks between the midwife’s phone call and the end of my pregnancy, Moriarty’s novels became my personal refuge, filled with laughter, hope, and the buoying joy of a happy ending. I slept, and woke up, and read books, and discovered I could bear the world a little better.

*

When we describe a story as escapist, we don’t necessarily mean it as a compliment. It’s a word too often tinged with suspicion or disapproval, as if the worthiest books are ones that require readers to maintain unflinching eye contact with reality. But in those times when we can’t bear to give reality even a sidelong glance, escape can be exactly what we need. Stories that transport us to other worlds are perfectly worthy in their own right: They can interrupt our anxious ruminations, boost our spirits, and give us hope and comfort in challenging times.

These sorts of books might be particularly important for children, who often have fewer practical tools than adults do for combatting life’s small and large difficulties. A child can’t do much to control their own world, but they can tuck a favorite book into their backpack for strength, and over the years I’ve spent writing novels for young people, I’ve gotten letters from readers who’ve done just that.

I’d guess that most of us who have the privilege of writing for children have heard from readers who’ve escaped into our books after conflicts with friends or parents, during cross-country moves, or in times of illness, anxiety, or grief. Books help kids persevere. And because a few of those kids and their families have shared stories like these with me, I’ve come to think of building escape pods as my most important creative duty. I want to help young readers explore big ideas, of course, and spark their love of language, and encourage them to ask heaps of questions—but more than any of that, I want to give them a literary refuge when they need it most.

Not that this is a straightforward task, or even one a person can accomplish on purpose. Your ideal escape pod might not look quite like mine. A story about witty Australian teens won’t feel like a world apart to readers who happen to be witty Australian teens themselves, which is one of the countless reasons why we need all sorts of books for all sorts of audiences. Still, when I sit down to write, I think about the story elements that transport me as a reader, and I hope that my work will find its way to other readers who feel the same.

I write fantasy novels, mostly—books that might as well be marked with brightly lit signs advising readers that they’re leaving their own world behind, and that a world of magical impossibilities is ready to welcome them in. The sorts of problems that arise in imaginary lands (turning a powerful wizard into a blob of glop, running afoul of an entire pirate league, or accidentally ripping a hole in the fabric of space and time) are serious business for the characters who have to solve them, but they’re a safe distance removed from whatever real challenges an elementary-school reader might be facing.

And while even fantastic tales can’t afford to be anything other than emotionally honest, a story’s conflicts and hard truths can be generously leavened with warmth and humor. Brave protagonists can be supported by true-blue friends and wisecracking sidekicks; even the tensest confrontations can stand the intrusion of a joke or three. Even when it might not be narratively wise, I can’t resist writing scenes set around kitchen tables, slowing a story’s pace just enough to let characters breathe, banter, and care for one another. When kids ask me why I tell the stories I do, I explain that I write funny books because I love to laugh, and that I write fantasy books because I love to imagine, but I think an answer closer to the truth is that I’ve always found magic and humor to provide sturdy, reliable transportation when I need to visit a world beyond my own, and I’m hoping to bring my readers along for the ride.

*

In the spring of 2020, the world was a place that plenty of us wished we could escape, although we couldn’t even leave our own homes. I filled my days with the usual pandemic-era tasks: attacking the groceries with Lysol wipes, wondering if homeschooling a toddler was a thing a person could actually learn how to do, staring helplessly at my phone, scheduling my panic attacks in convenient five-minute timeslots, and envying my adorable, clueless newborn. I tried to read, but I couldn’t stay focused.

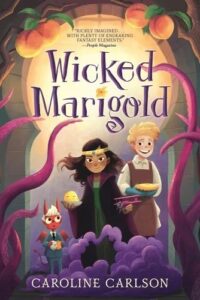

In this particular crisis, though, I found that I could write. Each morning, while my children slept, I sat down at my computer and worked on the most unapologetically escapist story I could think of—a story that eventually became my book Wicked Marigold. I began with the words once upon a time, because even the youngest readers know that those words hold the promise of happily ever after. The magical world I wrote about was full of scheming villains, calamitous curses, and imperfect princesses, but it was also a world in which villains could be defeated, curses could be reversed, and even an imperfect princess could discover the benefits of being perfectly herself.

I crowded the pages with jokes: good ones, bad ones, I didn’t really care. Laughter felt precious, and if a line made me laugh, it stayed. I settled my characters around the kitchen table, gave them each a slice of peach pie, and nudged them toward joy. Each day, I’d write another page. Each day, I’d leave the world for an hour or so, gathering the strength I needed to return.

Maybe that’s the secret magic of literary escapes—that writers find solace in them just as much as readers do. That a story can bring comfort both in the listening and in the telling. These days, I’m comforted not only by the escapist stories I tell but also by the down-to-earth possibility that those stories might someday reach readers who need them. When kids find Wicked Marigold at the bookstore or on a library shelf, I hope they’ll laugh. I hope they’ll escape for a while, if escape is what they need. And I hope that when the story is over, they’ll feel more prepared to meet reality’s gaze, unflinching.

______________________

Caroline Carlson’s Wicked Marigold is available now via Candlewick Press.