What Does It Mean to Write after Having Children?

Lightsey Darst on the Eternal, Fleeting Moments of New Motherhood

“You won’t write a word for five years,” a friend said when I told her I wanted to have children. But as soon as I heard it, I knew I would defy it.

If we interpolate a rule of five years per child and take into account that I ended up having two children two and a half years apart, that gives me a period of seven and half years during which I should not have written a word—April 2015 to November 2022, from the birth of my son until my daughter turned five. During that time I revised and published my third book and wrote and finished my fourth.

To abandon poetry would have been to abandon my identity, my calling, my deepest response to life. And, despite the gentleman who, upon learning that I was a writer, gestured to my pregnant belly and said, “You’re doing the most creative thing you’ll ever do,” I had an intuition that making people would turn out to be a different kind of creative act than making poems. As Sarah Rose Nordgren writes in her chapbook The Creation Museum,

Making a baby is not like making a poem, though it’s true they both can form unbidden. True that the world is required. Think of it this way: You can get a good start, but you can’t dredge up a whole baby on a winter morning when struck by a mood.

That lovely description in the last line suggests a question: what did writing mean to me back then? Before I had children, time spent writing felt luxurious, an affair among the beloved mind, the beloved page, and the wonderful skeins of words. I loved to do it, and when I did it, everything around me opened out while I plunged deep into inner space. I was a landscape architect viewing fresh ground from a hot air balloon. Or like God: I loved the high of creative power.

After I had children, all that changed. My beloved inner space collapsed like a deflated bounce house. I was constantly thinking about my children—if thinking is even the word for that low-grade fever of planning, worrying, and imagining, that constant projection towards them of a mental-emotional aura like a second placenta.

The mathematician Ingrid Daubechies found that she could not perform advanced mathematics for months after the birth of her child. As Siobhan Roberts writes in a recent profile, Daubechies went on to warn female colleagues about “the baby-brain effect”:

“I could not imagine that I would ever have trouble thinking,” Lillian Pierce, a colleague at Duke, says. But when it happened, Pierce reminded herself: “OK, this is what Ingrid was talking about. It will pass.”

I love the office feminism of this story, but I balk at the dismissal of the postpartum mind. Maybe math has no use for maternal thought, but when I could reflect, I felt as if I had discovered a new stratum of realities—new to me yet making up the total adult lives of many of my foremothers. Here was time, freshly recast as a measure of how much nutrition I could get into my nursing child. Here was space freshly carved into what fit in the reach of my arm. Here was everything I knew as a precondition for what they could know. Difficult as it was, I did not want to disregard my new reality as a place to write from.

I would like to leave this essay here, in an unfolding of feminist maternal poetics. But I had feelings—terrible feelings. Guilt over minutes stolen from my family to write. Desperation: I said I knew I would go on writing, and that’s true, but I was also driven by a creeping fear from constantly peeking into a world in which I had given up. Other than my husband, all day long I was surrounded by people who didn’t care whether I ever wrote another word, including my beloved children, and I felt everyone else’s reality impinging on mine. Shame over the state of my writing, my narrowed field of care, my now quite bourgeois-looking life (because with kids came a full-time job and then a house). Impelled and impeded, I wrote messy things, angry things, things full of helpless and ugly truths. I felt exposed, overemotional, selfish. And I had bad feelings about my bad feelings too: bitter, embattled, sometimes so sad.

It helped to have writer-mothers in the culture and in my life—a friend who sent me The Grand Permission, even. To have editors who valued my writing and a partner who believed in me, all that was a net in my abyss. My abyss, where I lived, where I wrote, my abyss of love and need and lightning—which I thought was simply my new life. But I was wrong. Because around the time my daughter turned five, like the mathematicians, I got my mind back. It’s not the same mind exactly—this one includes an eddy around the fact of my children—but space, flight, stunning perspective have suddenly all returned to me.

I can’t tell you what a surprise this is. And it makes me wonder whether I could have been spared the worst of it. Could I, like the mathematicians, calmly have placed my faith in the future? Could I have smiled at my friend: “You’re right, I won’t write. But five years is only time, and time passes”? But then I would have denied the poet of that time and thrown away her book. And her book was the truth of her life, and that truth matters to me. It matters to me because I lived that life, because someone else is living it now, because somewhere in the folds of the universe it goes on forever.

So if I could revisit the Lightsey of that time, maybe I wouldn’t disturb her. She had important work to do, after all. She had children to raise and a reality to bring to the page. Maybe I’d refill her water glass, tilt the light, bring a new book to her stand. If I could, I would touch the scene with mercy and with some sense that, eternal as this moment is, it will pass. Here was I, holding a child who would eventually hold herself. Here was I, tunneling through a wall that would give way. Here was I, writing, as a future memory.

_________________________

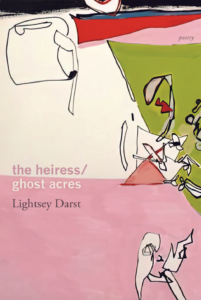

The Heiress/Ghost Acres by Lightsey Darst is available now via Coffee House Press.