What Does It Mean to Read Great Food Writing in a Pandemic?

J. Kenji López-Alt on Editing an Anthology as Coronavirus Hit

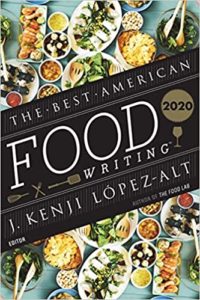

I had finalized the list of articles to include in Best American Food Writing 2020 by early February of 2020.

Before I had a chance to write my introduction, the coronavirus pandemic hit, and everything else suddenly seemed trivial. What relevance does food writing have in a world where restaurants don’t exist? What role could chefs play during a global pandemic? Why should I care about the death of the Kansas City taco or the local supermarket, when I have the potential actual deaths of hundreds of millions of people to think about?

In other words: What value did these stories, which seemed so relevant at the time, have in a world where restaurants and food writing as we know them have ceased to exist?

I, like many chefs and writers, work best under intense, immediate pressure, and by early March we were hurtling over the mountains with no landing strip in sight, building the plane as it was flying, and all I could see was that sheer rock face looming up in front of us.

At first, the work was figuring out how to keep our customers and staff safe. Do we need to stop selling salads? How many people can we seat at a time? How about the table condiments? Is it better to have servers wear masks for safety, or will that make customers assume that they are sick? I spent over a week on the phone with virologists, infectious-disease specialists, and food-safety experts vetting every aspect of our operations to ensure that our food posed as little risk to customers as possible. By March 8 we were using throwaway single-use menus, the condiment bottles had been removed from the tables, parties were staggered so that we filled only half the restaurant at a time, and servers were instructed to lean as far back from the table as they could during necessary up-close interactions.

A few days later, as the virus spread in the United States and the first deaths were being reported, we decided to shut down full-time operations, transitioning to a takeout-only menu. By the next day, it became official when San Mateo County mandated that nonessential services would be shut down entirely.

The value of good writers seems harder and harder to place in a media landscape that demands all writing be free and fast.

As a restaurant owner and chef, my business was placed under the “essential” blanket, allowing us to stay open for takeout and delivery service even as the businesses around us locked their doors for the indefinite future and fellow business owners hunkered down to shelter in place.

At first, the “essential” title was a relief. We can keep at least some of our people employed. We can pay our rent. We can limp along until we’re finally allowed to reopen. I worked quickly with my partners and teams to brainstorm strategies for how we could best serve our community while bringing in at least some revenue for the business—ideas that changed daily as new information about the virus was received and new rules of operation were disseminated by the county. We talked about doing retail business, about take-home meal kits, about gift cards and drinks coupons, about Web-based classes and personal deliveries.

I started spending my nights at the restaurant, repurposing the inventory in our walk-in freezer and pantry to put together meal boxes that I delivered to hospital workers and community centers. I also left packed meals at the restaurant for our laid-off staff to pick up in case they were struggling with no job, children out of school, and in some cases, immigration statuses that left them in-eligible for unemployment benefits. Meanwhile, my business partner Adam tended to his newborn baby while simultaneously navigating the bureaucratic and accounting nightmares involved with securing the loans and government bailouts we’d need to survive.

As I cooked alone at night, soaking 25 pounds of chickpeas for vegan meals, or sliding 80 pounds of marinated pork shoulder into the combi-oven to slow-roast overnight, I couldn’t help but note the bittersweet luxury of having a kitchen empty of line cooks and a dining room empty of customers. The long communal tables that once seated 24 guests were big enough to be laid end-to-end with a full 120 compostable takeout boxes.

It was then that I realized why these stories—the stories written when restaurants still had more than a glimmer of hope—matter.

The value of good writers seems harder and harder to place in a media landscape that demands all writing be free and fast, and where smaller magazines, newspapers, television and radio stations, and bookshops are being swallowed wholesale by giants like Amazon. Joe Fassler’s piece on the disappearance of grocery stores and regional supermarkets shows how the same problems media faced in the past decade will play out in the retail food industry in the next (spoiler: Amazon is at the center of the story in both cases). I can’t help but think of the flotilla of mom-and-pop restaurants and food businesses that will founder in the wake of the coronavirus, and the possibility that neighborhoods once defined by their unique food culture may lose their individuality.

If you want to see the value of good writing in action, you need look no further than Meghan McCarron’s piece celebrating the new diversity of Portland’s food scene in a landscape that fell victim to its own hipsterism (and the veneer of diversity that was painted over Oregon’s troublingly racist past).

Stories about people, places, authenticity, and the rich diversity of America’s food scene seemed particularly relevant as the question of what it means to be American has been at the core of recent politics. I loved José Ralat’s account of the rich history of the Parmesan-dusted Kansas City taco as a metaphor for Mexican immigrant life in Middle America at the turn of the 20th century, now being erased by the internet’s demand for “authenticity” (and I’m glad I got to taste them last time I drove cross-country—make sure you do, too). Like Sho Spaeth, I’m a Japanese American hapa who is not quite sure how to feel about the caricature of pseudo-Japanese culture that is Benihana. (Side note: my first ever restaurant job was wielding spatulas behind a hibachi-style grill.)

If anything, these stories are even more powerful now during the coronavirus pandemic, as minorities and lower-income individuals face the highest odds of contracting the disease. The kitchen workers (often undocumented immigrants ineligible for unemployment benefits), truck drivers, farm laborers, and factory workers that form the backbone of our food industry are being forced into choosing their livelihood over their health and the health of their communities.

My weekly free meal deliveries also include another group who have been disproportionately hit by the coronavirus: the elderly and mobility impaired. Laura Hayes’s matter-of-fact look at the difficulties of dining out while impaired could not be more relevant now.

We’re used to writers asking us: Is cheap food worth the hidden costs? Is a factory worker’s health worth $1.99-a-pound ground beef? Should I care about that uninsured Amazon or McDonald’s worker when a value meal is such a value? But Kwame Onwuachi’s memoirs shows us that even in the exalted kitchens of Thomas Keller himself, abuse and exploitation are the norm. Thankfully, the industry has been changing steadily for the better in the two decades since I started cooking professionally.

If Anthony Bourdain’s Kitchen Confidential solidified the image of the professional kitchen as the last bastion of sex, drugs, and rock and roll, the #MeToo movement and Bourdain’s own ante-mortem regrets showed us why, perhaps, that macho culture and the abuses it encouraged ought not to be tolerated anymore. The restaurant industry is, ironically, trying to shed the very image that made household names out of chefs in the first place, and that irony is not lost on writers like Hannah Goldfield. Her piece on the newfound sobriety of Joe Beef chef David McMillan encourages the positive changes he’s made in his kitchens while vividly showing how things got so bad, and making us question whether it should have ever been celebrated in the first place.

Cynthia Greenlee shows us the flip side of that coin in her piece on the gendered weaponization of food in the most literal sense (grits thrown at cheating spouses). So does Brett Martin, in his piece on NOLA chef Tunde Way’s political performance-art dinner parties.

Good food writing, just like good cooking, need not be too serious, and not all rockstar chefs made their names through bad behavior. It’s good to be reminded that the wholesomeness that first made Jacques Pépin into the king of television cooking has carried him through to the internet age. Joshua David Stein dives into the history of how Pépin’s five-minute, 52-second segment on making a French omelet, first recorded for San Francisco’s KQED in 1995, is now one of the most beloved and well-watched cooking segments on YouTube.

A pair of stories by Kim Severson and Kat Kinsman document the respective rise, fall, and potential rise again of Jamie Oliver and Rocco DiSpirito. They, like The Sopranos did for gangsters, show us the human side of seemingly once swagger-filled, infallible TV chefs (and unlike that show, are inspirational and hopeful in their advocacy of self-reflection and improvement).

While restaurant reviews seem almost like a cruel joke in the current situation (what restaurant needs to be criticized right now?), good writing is good writing, and nobody has perfected the art of the classy takedown like Pete Wells. When restaurants do finally, hopefully, reopen, we’d all do well to pay attention to writers like Korsha Wilson, who question who, exactly, are professional reviewers writing for, and how it would look different if Pete Wells (despite his eagerness to take down stalwarts like Peter Luger) weren’t the one defining what good dining was in modern New York.

These stories are not just stories about cooking and eating. These are stories about culture. About how food shapes people, neighborhoods, and history.

Even big businesses fail from time to time, and I always find it fascinating to peek behind the scenes. Kaitlyn Tiffany’s look at how Lean Cuisine pigeonholed itself into a false-diet corner, Tim Murphy’s retelling of the story we all thought we knew about how and why New Coke failed (it didn’t die, it was killed by a southern rebellion), and Katy Kelleher’s look at the dubious science and marketing behind the modern phenomenon of “raw water” make poignant connections between the very human individuals behind corporate-sounding messaging.

Finally, a pair of stories by Burkhard Bilger and Alex Van Buren about babies and food particularly struck me, as I simultaneously want to feed my daughter everything and eat her up at the same time.

More than anything, being in lockdown with a toddler who is unable to socialize and learn through the channels we have gotten so used to has shown me the value of socialization, the value of internal and external reflection, the value of having a good laugh, the value of neighborhoods and people, the value of diversity and culture, the value of history and technology, the value of education, and, more than anything, the value of being asked to participate in a world that extends beyond the boundaries of our four walls, of being challenged and provoked by thoughts outside of our own.

This is why food is important. These stories are not just stories about cooking and eating. These are stories about culture. About how food shapes people, neighborhoods, and history. Now, more than ever, as we face the very real prospect that the bars and cafés that have played pivotal roles in our social lives, the restaurants that have come to represent a neighborhood, might be lost for-ever, we must remember what it is that we risk losing and turn our minds outward, even as we are forced to isolate.

By mid-April I was able to hire back enough management and production staff to box up over 500 free meals per week. And when I finally was able to take my nose off the grindstone, I lifted my head to find a world in which organizers and everyday people had already begun figuring out ways to help people fill those very real needs for human connection. I was awestruck by the selfless front-line healthcare staff working overtime to care for those in need, by the researchers who spent endless days and nights toiling in labs, by concerned out-of-work individuals reaching out to the elderly and homebound to make sure their needs were met. The pandemic has revealed the true heroes among us. Chefs and writers may not be heroes, but even heroes need to eat, socialize, and be provoked, and wherever there are empty bellies to be filled and too-comfortable minds that need poking and prodding, chefs and writers will be there.

__________________________________

Introduction from Best American Food Writing 2020 edited by J. Kenji López-Alt and Silvia Killingsworth. Introduction copyright © 2020 by J. Kenji López-Alt. Reprinted by permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

J. Kenji López-Alt

J. Kenji López-Alt is the Chief Culinary Advisor of Serious Eats, Chef/Partner at Wursthall, and the author of the James Beard Award–nominated column The Food Lab. His first book, The Food Lab: Better Home Cooking Through Science is a New York Times bestseller, winner of the James Beard Award for general cooking, and was named Book of the Year by the International Association of Culinary Professionals. He lives in San Mateo with his wife Adriana and daughter Alicia.