What Does Gentrification Have to Do With Writing Place?

Jendella Benson on Personal Monuments and Their Memories

In her book, This Here Flesh: Spirituality, Liberation, and the Stories That Make Us, Cole Arthur Riley writes, “Place is the one thing that always is. We are always somewhere. I have been without people but never without place.” And place, for me, is always important. In my favorite books it’s a character in and of itself; it shapes interactions; it forces people together or apart; it carries with it an atmosphere, an ideology, a demeanor that imprints itself upon the people that live within it.

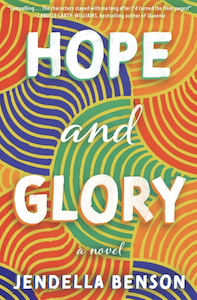

In my debut novel, Hope and Glory, that place is Peckham, a neighborhood in southeast London famous for many things—not all of them good. Like everywhere, Peckham is changing in rapid bursts and a slow, gradual creep. Gentrification feels so cliché to type—it actually makes my skin crawl—but that is what is happening and that is why I cannot afford to live there anymore.

But “gentrification” doesn’t explain what happens specifically to a place. It is a flat term that speaks of boxy rooms in new build apartments and nameless hipsters and craft beer. It is an indiscriminate brush—a whitewashing in and of itself. It doesn’t pay homage to the idiosyncrasies of a place, the specific fingerprint of a community that is being erased. I wanted to preserve that version of Peckham on the page, beyond a snapshot of how things look. I wanted to capture how Peckham feels to me.

The beginning of my novel starts with a homecoming—Glory is returning from LA to London as her father has died—but what does a homecoming feel like? What are the surfaces that a finger is drawn to? What are the sounds and smells that a homesick mind didn’t realize it had missed? What are the personal monuments that stand in relief and form a reminder that this is not a dream or a hallucination, you are actually here embodied, in the flesh?

I think these personal monuments are the most important. They immediately transfer authenticity and dimension, because what is a place without the memories of the people who live there? Without the wear and tear from bodies and lives rubbing against the stone and concrete and glass, a city does not feel real. It becomes a model village, photographed in shallow focus to make it appear more dimensional than it actually is, but we can sense its uncanniness, our eyes searching to find the gaps in plausibility.

Memories are also geographical markers, as real as the physical place that becomes their stage. The place is not just a happenstance or a prop, it is part of the memory itself. A conversation happens in a particular way because of where the participants are in relation to each other. It matters that one of them was sat on the red plastic bench of the bus stop, her knees bouncing in irritation as she listens to her partner’s complaint (her knee can only bounce that way because of what she is sat on, its height and the shallow-depth of the seat).

I think these personal monuments are the most important. They immediately transfer authenticity and dimension, because what is a place without the memories of the people who live there?

It matters because it is when the other participant sees the bouncing knee, that the tone of their voice changes because they are irritated that she is irritated. But as they are standing at a bus stop, there are others nearby who overhear, who insert themselves into the narrative because it looks like one person is towering over the other.

If this argument was to happen somewhere else, the physical dynamics could entirely change the atmosphere, the events, and the outcome. But it happens there, and the details of that place become embedded in the DNA of the entire memory—or for our purposes, the entire scene, chapter, or book.

It’s important to remember that memories are physical experiences, as much as they are emotional ones. A friend was admitted to a psychiatric hospital for a while a few years ago, and I remember going to visit them on a dark and damp evening. The shadows in the hospital entrance and the feeling of raindrops dripping into my collar all heightened the emotional strangeness of going to visit a friend on a psych ward. When Celeste, Glory’s mother, is admitted to a psychiatric hospital early on in my novel, it was the memory of those sensations that helped me to construct the hospital environment and map out Glory’s visit with her mom, even as the narrative differed from the actual events of my memories.

World-building is often an exercise associated with fantasy, science-fiction, or dystopian literature. When the author is creating a world or environment from scratch, it makes sense that early on in the writing process significant time is given to plotting and planning the environment the book exists within, and one would expect a certain level of research for existing environments that an author is unfamiliar with. But when we are writing about places we “know,” this kind of knowledge should not be taken for granted. Familiarity breeds, if not contempt, then a lack of awareness. Certain things become invisible to the complacent eye, and to intimately acquaint a reader with a place, even the most innocuous details matter.

Saying all this, though, is it possible to overwrite a place? Absolutely. But that is what the editing process is for. Like anything else, how you write place needs to ultimately serve the narrative you are shaping. In a particularly emotional reunion scene in Hope and Glory, the notes from my copyeditor said that too much description was slowing down the pace. I begrudgingly cut paragraphs, but afterwards I understood that the extra words had already served their purpose. Through overwriting, I had thoroughly situated myself in the scene, and now I was able to cut away the excess in confidence, deciding the pertinent details that would efficiently transport the reader to a place that I already felt to be real.

__________________________________

Hope and Glory by Jendella Benson is forthcoming April 2022 through William Morrow.

Jendella Benson

Jendella Benson is a TedX speaker and popular writer and editor for Black Ballad. Her work has appeared in The Guardian, and on BuzzFeed, MTV News UK, and The Huffington Post, among many others. She lives in London. Her book is Hope and Glory.