What Data-Driven Corporate Medicine Has Wrought

Terrence Holt Revisits Paul Starr's Classic, The Social Transformation of American Medicine

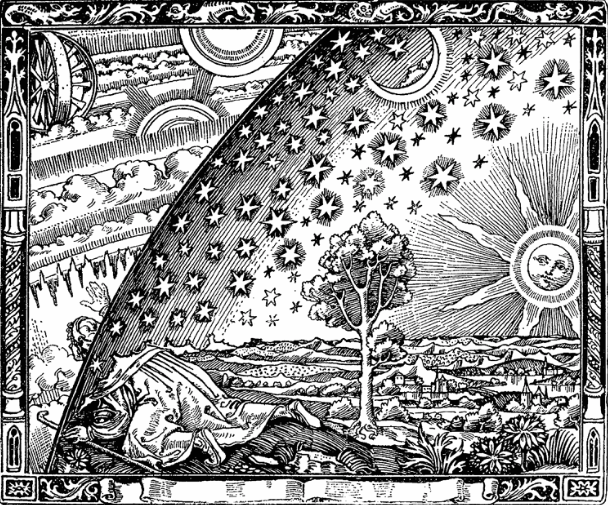

There is an engraving you have probably seen, done in a late-Medieval style, depicting a young man sticking his head through the starry sphere and gazing, amazed, at the machinery of the Universe. This is how I feel when I read history. Like the man in the picture, we inhabit history without grasping it. Even when we glimpse its workings, it takes a historian to make sense of what we see.

I was reminded of this by a story a younger, computer-savvy doctor told me last year, about a time he caught a glimpse of the primum mobile of his world—and realized later that he had entirely missed its significance. The hospital where he works had adopted a new electronic medical record. Despite the description, the program wasn’t primarily a medical record. It was billing software, designed to massage medical information in ways that would yield the highest returns.

Neither of us was scandalized about this. It’s hard to blame a hospital for trying to get paid. What did scandalize my friend was when he found that with the right sequence of clicks this new program could display something called the “performance characteristics” of every one of his colleagues, listing (among other things) how long it took them to sign off on their progress notes. Many of his colleagues, he found, like himself, tended to be a little late.

Let me explain: to many doctors, chartwork is drudgery. Patients come first. To hospitals, progress notes are the quantum unit of production, what a hospital must have in order to bill an insurer. The kind of procrastination we were discussing was ordinary enough, just the ancient push-pull between employer and employee. Seeing that procrastination laid out and anatomized for everyone to see: that felt a little scandalous—an indecent airing of private sins, probably a glitch in the program, but really nothing more.

But it was more than that: “I realized later that data represented the performance characteristics of everyone in the hospital down to the slightest detail. Suddenly we were all working for the machine.” What my friend had seen turned out to be the first stirrings of a vast machinery that was about to change his world. The quantity of data the machine could collect, the high-resolution analysis it enabled of the physician’s every minute, had shifted the balance. Blind to what might actually be going on within those minutes (where the doctor and patient might be discussing, say, a newfound cancer), the machine focused simply on counting them, dictating what care doctors could provide based on standardized metrics, and not on individual human needs. “It’s not like we didn’t have to meet standards before this,” my friend concluded sadly. “It’s just that they’re able to police us now so very, very closely.”

I thought about both that woodcut and that conversation, when I read the new updated edition of Paul Starr’s The Social Transformation of American Medicine (Basic Books, 2017). Starr’s brilliantly incisive history charts the rise of medicine as a “sovereign profession,” one that, over the course of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, acquired the power and prestige to put itself above many of the forces constraining the rest of us in our daily lives. Starr’s is a meticulously researched social history of a profession viewed always in the context of the larger sweep of history it inhabits.

Starr begins his narrative in the colonial era, when practitioners had to carve out a new position in a new society: American medicine started at a disadvantage. Without the aristocracy that had, through its patronage, enabled British doctors to claim a place above the ruck of common tradesmen, colonial doctors confronted an ongoing struggle for authority. In a nascent democracy, claims to superior knowledge were suspect.

Along a thinly-populated frontier, the difficulty of gaining access to a physician forced isolated farmers to rely on their own skills. Ideology and geography threatened to strangle the authority of American medicine in its cradle. Starr traces the profession’s recovery from its awkward beginnings through the nineteenth century, as medical organizations pushed for state regulation in order to restrict the activities of competing theoretical schools such as homeopathy. The birth of the modern hospital out of the Civil War, the growth of public health legislation, and finally the rise of an effective medical practice based in a scientific understanding of disease, all led to the establishment of a profession vested with the authority of a state within a state.

Committed doctors will still find ways to give time to their patients, even beneath the full weight of the corporations’ pressure to “perform.”In its struggle to overcome its early weakness, the profession succeeded possibly too well. The sovereignty Starr sees medicine attaining in the 20th century allowed it to a great extent to police its own members, charge its own rates, practice how it saw fit, and to fight off anything it viewed as an encroachment on these prerogatives. This sovereignty helps Starr explain as well why medicine came to view itself as standing apart from society at large—exempt not only from economic and political forces, but from social and cultural influences as well. In capturing this peculiar, essential aspect of the mindset of American medicine at its apogee in the mid-20th century, he sets up the tragedy that emerges in the extensive epilogue appended to the new edition, tracking events from 1982 to 2016.

Starr charts the decline and fall of medicine’s sovereignty under a broad range of political and economic forces. Burgeoning research led to increasingly expensive medical treatments and technologies. International competition led corporations to offshore and downsize, shedding benefits as well as employees. Consolidation of medical care within large corporations created a world in which the sovereign physician became an expensive luxury, reserved for those who could afford to sign on to so-called “concierge practices.” We are all familiar with the larger outlines of this story, which seems to have culminated with the passage of the Affordable Care Act.

But the story has continued past this epilogue. Events move so quickly now. We might read the final chapter of that fall as written not on bureaucratic quadruplicate, but in binary. Where Starr’s epilogue grants one paragraph to the impact of the electronic medical record, just three years later we have witnessed, thanks to information technology, the transformation of medicine into a panopticon, in which the doctor is no more sovereign than any other cubicle-dweller, one more element in a system striving toward optimization of outcomes.

This was what my friend had glimpsed, that day he peered into the works of the electronic medical record. Thanks to Starr, we have the context to understand what his story means—not just to one physician, but to all of us, doctor and patient alike.

If we are not inclined to sympathize too much with doctors in their loss of sovereignty—they remain, after all, well-paid cogs in the machine—the means by which the profession fell, and the forces that made those means so powerful, nevertheless affect us all. The world moves quickly, but this feels like a familiar story already: through information technology, capital amasses to itself new forms of value—forms composed of bits of information about everybody—and deploys this new wealth to shape the world to its advantage. Information technology enables corporations to squeeze the last quantum of value out of the resources—chiefly human—at hand. The medical profession has fallen into the same mill grinding up everybody in our era, in a world in which everything can be monetized, down to the smallest fragments of our lives.

In choosing to view physician “performance” (defined God knows how, but unlikely in a way that has anything to do with patients’ well-being) as a resource no different from any other commodity, the corporations now marketing health care to the public have given doctors reason to worry about who those corporations imagine should command physician loyalty. It’s hard to picture this disrupted world as one where the patient is supposed to claim the doctor’s allegiance. If the doctor-patient “encounter” is imagined as a line in accounts receivable, that makes it much harder for it to be honored as an episode in a relationship.

What new chapter we are about to open in the history of medicine is difficult to foresee. But I wonder if the digital panopticon is really the end of the story. The panopticon is never as perfect as the individual fears—or the corporation wishes—it to be. Orwell understood this, and this is why he gave Winston Smith his oddly shaped apartment, where—out of view of Big Brother’s all-seeing eye—he still could make his own moral choices. Committed doctors will still find ways to give time to their patients, even beneath the full weight of the corporations’ pressure to “perform.” They will and can continue to do so, I believe, for two reasons. They will, because medicine (if we imagine that word can still refer to individual practitioners rather than a mass of employees) still subscribes to a moral code in which the needs of the sick must come before the demands of the corporation. They can, because the structures of knowledge and power we inhabit are everywhere full of gaps.

The moral code speaks for itself. As for an individual physician’s continuing freedom to choose that code over the corporation: I come back to that engraving, and the curious, daring figure breaking through the scrim that hides the workings of his world. I admire his spirit, though Orwell understood how fantasies about individual spirit come to grief in the grip of power. Seeing in the engraving now some kind of allegory—the individual physician, my young friend getting a glimpse of the iron law coming to rule his world—I can’t help but feel the weight of all that machinery. And wonder if we can count on the efforts of overburdened individuals to save us all from the tyranny of that mill.

And yet—consider as well the most important fact about that engraving. It’s not Medieval at all, but the work (most probably) of Camille Flammarion, the popularizer of science who first published it in the late-nineteenth century. Done to look like a Medieval woodcut, and mistaken as such by readers for generations until historians set us straight (although, to be fair, Flammarion never offered it as antique), the image’s resonance suggests how we tell our stories, and the nuances with which we understand their relation to history, both matter. Each in its own way helps us puncture constraining frameworks.

In representing an exploded paradigm, this engraving tells us something important about all such paradigms, about the limits of the power to be gained by the deployment of knowledge. Understanding the picture not as an artefact of history but as a retrospective comment about history relocates its meaning. No matter how complete we think our understanding—and in this I include also the corporations in their deployment of Big Data’s all-seeing eye—there are always gaps, fundamental flaws in the way we have framed the situation, things we have taken as fact that turn out, on examination, to be anything but—misprisions and misrepresentations suggesting the ultimate vulnerability of structures built on an unquestioning faith in the power of data. Compelling accounts like Starr’s that so brilliantly document and carefully locate us in social history help us see that the machine isn’t always what it presents itself to be.