What Culture Shock Taught Me About Sci-Fi and Fantasy Storytelling

Alex Jennings on the Experience of Otherness, and Learning to Ask Questions

The Motel of the Mysteries by David Macaulay was my favorite children’s book growing up. It was a 1979 illustrated satire based on Howard Carson’s discovery of King Tut’s tomb. The prose wasn’t dumbed down, and the content itself was endlessly fascinating to me. In 1985, a combination of junk mail and a mysterious[?] pollution that suddenly hardened in the air buried the United States and just like that, American society passed from the earth. A thousand years later, archeologists have begun excavating in a few sites, including a motel, which they take for a holy tomb situated in the midst of a sort of religious megacomplex.

At one point, one of the researchers demands to wear some of the religious finery the team has dug up, and puts a toilet seat (the “sacred collar”) around her neck with the sanitization strip (the matching headband) across her forehead, toothbrushes for earrings, and the bathtub drain plug as a pendant hanging from her neck. The illustration is purely ridiculous—all the more because of the serious dejected expression the scientist wears—but something about it colonized my imagination and clung to me for years.

Childhood is a foreign country. When I was small, I felt like an immigrant to a strange land where I was meant to learn the language, culture, and customs with what sometimes felt like minimal instruction—I did learn to read early, from my older sister, but that didn’t help me understand people any better, and that understanding seemed to come so easily and naturally to everyone else. I felt sure there would be trouble if anyone realized the depths of my perplexity. Then, in 1992, I moved from one foreign country to another. My family left Columbia, Maryland for Paramaribo, Surinam.

When he taught my class at Clarion West in 2003, China Mieville explained that as a teenager, he’d traveled from London to Cairo for the first time and that he’d been “absolutely cowed” by culture shock. Egypt was so different from anything he had known that his very body was forced to adjust to the place. He further explained what a powerful tool culture shock was in the arsenal of an SFF storyteller.

That sensation of suddenly being somewhere else, far from home, knowing little about the language, the social rituals, even the interpretation of commonplace concepts like radio and TV stations, fast food restaurants, and department stores, differing starkly from the perceived norm—I remembered that feeling. I’d experienced it many times. I knew viscerally what it must have felt like for Frodo Baggins to arrive in Rivendell.

This is what drew me to SFF to begin with. That experience of otherness was key, but so was the connection between others who could learn to understand one another even if that understanding was incomplete.

It was living as an expatriate in Paramaribo that I discovered a trove of Asimov’s and F&SF back issues and SFF paperbacks in the American Embassy’s Community Liaison Office. I was already familiar with Tolkien and C. S. Lewis, but it was there that I discovered the works of Ursula LeGuin, Nancy Kress, and Octavia Butler. Butler’s work especially struck a chord with me as I realized that the people she wrote about in Dawn looked like me. The sense of separation and of loss I’d always felt became something else—now instead of feeling like something to be punished for if I was ever found out, it felt glorious, as if I’d suddenly tumbled into another world, the first human to set foot in a hidden kingdom.

After two years in Surinam, my family picked up and moved to Tunis, Tunisia, a country as different from the United States and from Surinam as those two were from each other. It was there that I discovered The Motel of the Mysteries. Reading this satirical take on American life and culture and on the guesswork involved in archeology added a deeper layer to my understanding of culture shock. It reminded me how easy it was to be completely wrong in my assumptions and also that there was a simple solution: instead of hiding my ignorance and trying to piece together clues on my own, I could just ask the people around me.

Sometimes it would go poorly, but most of the time it went very well. That was how I learned about Tunisian history, Tunisian cooking, and how important that nation was to the SFF that I loved. I learned that the desert planet Tatooine, from Star Wars, was named after a southern Tunisian village, that Obi Wan Kenobi wore a commonplace Tunisian burnoose, and that The Life of Brian was also shot in Sbeitla, Tunisia, years after Franco Zefirelli shot Jesus of Nazareth there, using many of the same extras, who guided the Monty Python crew through the process of filmmaking.

Tunisia was also part of the Maghreb along with Egypt. Like that country, it played host to ancient empires, fortified tombs, and a species of memory I’d never encountered living in Paramaribo or the United States. This much closer to the Pyramids of old, even the daylight had a different vibration.

This is what drew me to SFF to begin with. That experience of otherness was key, but so was the connection between others who could learn to understand one another even if that understanding was incomplete. I was so much more fortunate to enjoy my position than those archeologists making their ridiculous guesses and assumptions about an America that had long-since passed away.

Later in life, I moved to New Orleans, yet another place and culture foreign to me with its specific music, language, traditions, festivals, and joys. It was those earlier experiences that equipped me to integrate myself into the fabric of the city, to let New Orleans reveal itself to me rather than to impose my own assumptions or demands on it. So many people move to the city and find themselves uncomfortable with the social mores, the constant practice of music, and with the confidence and pride the people of New Orleans have in their culture and ways. Most people who move down tend to leave again within three years. I knew when I got here that I didn’t need New Orleans to be any one thing, I needed it to be itself.

Processing and adjusting to culture shock is a form of listening, of learning to parse cues until the dissonance fades into the background and new information can be understood and incorporated into one’s view of the world. It could be argued that adjusting to New Orleans must be much much easier and quicker than adjusting to somewhere like Tunis, but I found that the familiarity of so many aspects of New Orleans life contributes to the strangeness.

In a city full of mosques and minarets where, five times a day, the city is bathed in the elongated melodies of the Muslim call to prayer, it makes sense that things like visiting a grocery store or paying a bill are so different than they were in Washington, DC, but in New Orleans, which is so much closer to home, the steps of, say, renting an apartment or making weekend plans with a friend seem as if they should be as normal as they always have—but each of those processes has its own rhythm particular to this place.

In Tunisia is an archeological site called El Hawariya. It’s situated right by the Mediterranean Sea where the electric blue waves crash over and over on the rocky beach and where in ancient times, the Phoenicians who ruled Carthage kept slaves to excavate the sandstone they used to build their houses.

Generations of enslaved people lived their entire lives in that quarry, never once setting foot on the surface of the earth—and all of that history distills into the strange and haunted experience of walking through those tunnels, of seeing at the entrance a rock that has been weathered into the rough shape of a camel and is likewise trapped in that place, weeping and watching the water it can never taste. El Hawariya is one of the most alien places I’ve ever been. It looks like another planet, and seeing it helped me understand how George Lucas fell in love with Tunisia and decided to bring so much of it to the screen.

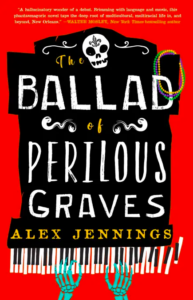

I’m no George Lucas, but in my novel, The Ballad or Perilous Graves, I’ve tried to capture that feeling of entering an entirely new world, of learning things that alter one’s understanding so completely that it divides one’s life into Before and After It’s not just travel, or living in foreign countries, that does that to us: every phase of life, every era is its own foreign country with specific geography, language, customs that at first seem truly unfamiliar.

Now that I’m in my forties, my perspective on life has changed both gradually and immediately many times over—and I hope it continues to. That’s why, when I look at my beloved Motel of the Mysteries, I imagine myself speaking to one of those poor blinkered archeologists, explaining to them what bowties or ice buckets are. It’s so difficult to piece this information together without a guide, without the mindset to appreciate and understand. But if one gets lost, confused, we can always simply ask.

_________________________________

Alex Jennings’ The Ballad of Perilous Graves is available now via Redhook.

Alex Jennings

Alex Jennings is a teacher, author, and performer living in New Orleans. His writing has appeared in strangehorizons.com, podcastle, The Peauxdunque Review, Obsidian Lit, the Locus Award-winning Luminescent Threads: Connections to Octavia Butler, and in numerous anthologies. His debut collection, Here I Come and Other Stories was released in 2012. He also serves as MC and co-producer of Dogfish, a monthly literary readings series. He is a graduate of Clarion West (2003) and the University of New Orleans. He was born in Wiesbaden (Germany) and raised in Gaborone (Botswana), Paramaribo (Surinam), and Tunis (Tunisia) as well as the United States. He is an afternoon person.