There are two types of women, Picasso said: “goddesses and doormats.” His ideal muse—helpmeet and source of creative inspiration—was a hybrid; decorative enough to hold the artist’s eye, and meek enough, as patient unpaid model, to maintain whatever pose he required of her without complaint. Ideally, she should be a biddable lover and accept that great artists had great appetites and she could not claim exclusivity in her role. If she also bore his children, kept house, cooked and took on secretarial duties, so much the better.

Picasso did not, of course, invent the arrangement. The history of western art can be read as a story of male genius, tortured and often truculent as it strove to make one pure, truth-telling mark on an imperfect world, supported by a legion of handmaidens whose self-abnegating silence was immortalized on canvas and in bronze—from Benvenuto Cellini’s abused Nymph Caterina, through the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood’s evanescent Lizzie Siddal to Picasso’s Weeping Woman, Dora Maar. Genius required it, exempting the artist from the normal rules of human relationships. Decency was for the mediocre.

According to Marina Picasso, the artist’s granddaughter, “His brilliant oeuvre demanded human sacrifices. He drove everyone who got near him to despair and engulfed them. . . He needed blood to sign each of his paintings. . . the blood of those who loved him.”

Many muses were themselves artists, like Siddal and Maar, their reputations doomed to be eclipsed by those of their lovers. Sometimes the neophyte muse was a young art student, intrigued by the chance to sit at the feet of an established master. Sometimes the muse was even younger. Dina Vierny was a spirited 15-year-old when she first posed naked for the 73-year-old sculptor Aristide Maillol. The inspiration of her voluptuous form was credited with reviving his career, and him, for the last ten years of his life. Balthus famously used girls aged between 11 and 16, often from working class families, as models for his dreamlike and disturbing, some would say quasi pornographic, paintings in which, at the very least, the question of consent must have been an issue. In his late eighties, he regularly took Polaroid photographs of a semi-naked eight-year-old, though he maintained that he did not have a sexual relationship with a model under the age of 16.

With Gauguin, there was no ambiguity or denial. He was a failed stockbroker turned impecunious painter in his forties, married with five children, when he left France alone for Tahiti in search of Eden. There he “married,” according to local custom, a 13-year-old girl called Teha’amana, who was said to have inspired his finest paintings, suffused with the lush languor of the tropics. Other muses followed, including Pau’ura and Vaeho, both fourteen. All cared for him, bore his children, and were depicted in his work as mysterious sensual Eves. In the blankness of their gaze they seem embodiments of the Sable Venus—colonized and objectified—as described in Robin Coste Lewis’s remarkable narrative poem, a telling inventory of western artworks and artifacts depicting black women.

“Even if you think people like you, it will only be a kind of curiosity they will have about a person whose life has touched mine so intimately.”

Frida Kahlo was a 14-year-old schoolgirl when she first met the painter Diego Rivera in Mexico City in 1922. In his autobiography he recalled: “All at once the door flew open, and a girl who seemed to be no more than ten or twelve was propelled inside. She was dressed like any other high school student but her manner immediately set her apart. She had unusual dignity and self-assurance, and there was a strange fire in her eyes. Her beauty was that of a child, yet her breasts were well developed. She looked straight up at me. ‘Would it cause you any annoyance if I watched you at work?’ she asked. ‘No, young lady, I’d be charmed,’ I said.”

They didn’t meet again until she was 18—he was in his late thirties—when she came to him as an art student seeking professional advice. Four years later they were married. Though she publicly presented herself as the mere spouse of a great artist, she continued to paint, and weathered condescending treatment from critics. “Little Frida’s pictures … had the daintiness of miniatures, the vivid reds, and yellows of Mexican tradition and the playfully bloody fancy of an unsentimental child,” wrote one critic in Time magazine. The marriage was turbulent and Kahlo, who had been badly injured in a streetcar crash, later said: “There have been two great accidents in my life. One was the streetcar and the other was Diego. Diego was by far the worst.”

Camille Claudel was a 21-year-old student when she arrived as an apprentice at the atelier of sculptor Auguste Rodin, who was in his mid-forties. She became his model, lover and muse and they worked together on some of his most celebrated sculptures, but the relationship was fraught and ended, to Claudel’s despair, after nine years.

The following decade, Gwen John, an accomplished artist in her twenties, came to model for Rodin, by then in his sixties and one of the most famous artists of the day. As the sister of the more famous, and flamboyant, artist, Augustus John, she must have been primed since childhood to shrink into the shadows. In her correspondence with Rodin, she always referred to the sculptor as ‘mon maître’, describing herself as “votre petite modee.” After a while, her letters were not returned. Rodin had moved on. She went on to have other lovers herself, women as well as men, but she became reclusive, focussing on her work and her cats in her Paris studio. Her reticence was evident in her subdued and delicate portraits of anonymous women. Finally, she seems to have faded away, like a watercolor exposed too long to sunlight. She died of starvation in 1939.

*

When Françoise Gilot first met Picasso, she was an art student of 21 and he, 40 years older, was acknowledged as the towering figure of modern art. She “felt that he was a person to whom I could, and should devote myself entirely, but from whom I should expect to receive nothing beyond what he had given the world by means of his art,” she wrote in her 1964 memoir, Life with Picasso.

Lucian Freud, was 55, a renowned portraitist and visiting tutor at the Slade School of Art when he asked a shy student, 18-year-old Celia Paul, if she would sit for him. It proved to be an exacting experience, as she recalls in her newly-published memoir, Self-Portrait: “When he came to painting my breasts, I felt his scrutiny intensify. I felt exposed and hated the feeling. I cried throughout these sessions. He tried to comfort me by telling me how much I pleased him. But I didn’t believe him, because the evidence of what he really felt was on the easel in front of me.”

Freud’s work was known for its visceral quality and he did not spare his many lovers, or his children, from the forensic cruelty of his gaze. Her first sitting launched an intense ten-year relationship in which Paul continued to model for him. They lived separately and when she gave birth to their son Frank, Freud—who was said to have fathered up to 44 children—had little direct role in the boy’s upbringing. Paul seems to have accepted this unquestioningly and, with a single-mindedness she might have learned from her lover, dispatched her baby to be raised by her mother in Cambridge so she could return to her studio. Throughout her relationship with Freud, her determination to continue with her painting had been a point of contention.

“He spoke admiringly to me of Gwen John, who had stopped painting when she was most passionately involved with Rodin, so that she could give herself fully to the experience. I felt that there was a hidden reproach to me in his words, and that Lucian felt that was what I should do.”

Later, when their relationship was under strain, Freud cited Rodin again, describing the sculptor’s hurt when he no longer had complete control over his lover Camille Claudel. Lucian said that he understood how painful that feeling is. His fellow-feeling is chilling when one recalls the fate of Claudel—desperate at being cast off by Rodin, she spent the last thirty years of her life confined to a lunatic asylum.

Freud’s final portrait of Paul was painted after her first exhibition, in 1987. In “Painter and Model” her eyes were downcast, her red dress was spattered with paint and her bare feet trampled discarded paint tubes. In her hand she held a paint brush, angled suggestively towards the genitals of a naked man sprawled on a couch. “I felt honored that Lucian should represent me in the powerful position of the artist: his recognition was deeply significant to me. But underlying my pride, I felt wistful that I was no longer represented as the object of desire.”

For many muses who outlived their usefulness, or their artist, poverty, obscurity, madness and/or suicide followed. George Dyer, lover and muse of Francis Bacon, killed himself in a Paris hotel on the eve of Bacon’s landmark exhibition at the Grand Palais, while artist Jeanne Hebuterne, wife and model of Modigliani, jumped to her death from a fifth-floor window the day after her husband died of TB. When Gilot told Picasso she wanted to leave him, he warned her: “Even if you think people like you, it will only be a kind of curiosity they will have about a person whose life has touched mine so intimately. And you’ll be left with only the taste of ashes in your mouth. For you, reality is finished; it ends right here. If you attempt to take a step outside my reality—which has become yours, in as much as I found you when you were young and unformed and I burned everything around you—you’re headed straight for the desert.”

“After he had spent many nights extracting their essence, once they were bled dry, he would dispose of them.”

The desert was what awaited Picasso’s other muses—mental breakdown in the case of Dora Maar, who received ECT for depression after he left her for Gilot; suicide for Marie-Thérèse Walter, who, according to Picasso’s biographer John Richardson, “had no social aspirations whatsoever. Her entire life was devoted to being the artist’s great love and muse.” Suicide was also the fate of Jacqueline Roque, Picasso’s widow and assiduous keeper of the flame.

Marina Picasso described her grandfather’s relationships with women: “He submitted them to his animal sexuality, tamed them, bewitched them, ingested them and crushed them onto his canvas. After he had spent many nights extracting their essence, once they were bled dry, he would dispose of them.”

But against this narrative of cruelty, self-sacrifice and sorrow there is a counter-story of the Muse Redux, the model-lover who reclaimed her own life beyond the artist’s studio. It’s pleasing to learn that Teha’amana, Gauguin’s first Tahitian “wife,” set up home elsewhere with her child and a new husband and refused to see the artist again. Pau’ura moved on too, enraging Gauguin, who took legal action against her for stealing kitchenware, including a coffee mill. He lost the case.

There is also the morally queasy story of the Predatory Muse, Patricia Preece, who enticed hapless Stanley Spencer away from his put-upon first wife, Hilda Carline, a gifted artist and mother of his children. Less than a week after his divorce, Spencer and Preece were married. She set the tone for their future relationship by embarking on honeymoon with her lesbian lover, Dorothy Hepworth, leaving Spencer behind. A startling self-portrait with Preece from that time shows Spencer’s head in profile, beaky and bespectacled, apparently kneeling, an astonished supplicant before the naked form of his new wife which is spread out before him like a backlit flesh buffet. Her facial expression is severe—look, don’t touch. Their marriage was never consummated and, once she got control of his finances, Preece evicted Spencer from his home.

But for most artist-muses, the real prize, honestly sought, was recognition for their own work, out of the shadow of the celebrated lover. Suzanne Valadon, who modeled for Renoir and became the muse and lover of Toulouse Lautrec, was later acknowledged as a considerable artist in her own right and in her mid-forties acquired a model, muse and lover of her own, 23-year old painter André Utter, whom she went on to marry.

The best revenge, however, as George Herbert wrote, is to live well.

In 1949, Lee Krasner showed her paintings in a groundbreaking New York exhibition titled “Artists: Man and Wife.” Krasner, who spent a decade nurturing the career of her troubled husband Jackson Pollock, was to flourish creatively in the years after his death in 1956 and, though she had to bat away questions about her long-dead husband all her life, she achieved recognition and creative fulfillment, as last year’s Barbican exhibition triumphantly showed.

Frida Kahlo lived long enough to see her work taken seriously but she would be surprised, and perhaps modestly abashed, to see that her reputation has far surpassed that of her husband. Posthumous recognition might be cold comfort to the dead but for the living there is satisfaction in seeing old wrongs righted at last. Camille Claudel is now widely acknowledged to have been a sculptor of genius. There is a room dedicated to her work in the Musée Rodin in Paris and three years ago the Musée Camille Claudel opened in Nogent-sur-Seine. Gwen John’s reputation and the saleroom value of her work have risen steadily since her death, and her work is held in major public collections including the Tate, achieving a recognition that her retiring nature might have recoiled from had she still been alive. And Picasso’s Weeping Woman could finally dry her eyes when the pioneering Surrealist photomontages of Dora Maar were celebrated with the opening last year of a major exhibition at the Tate.

The best revenge, however, as George Herbert wrote, is to live well. Dina Vierny, Maillol’s sturdy 15-year-old, though never vengeful and always protective of Maillol’s reputation, lived very well indeed. As inheritor of his estate, she set up the Musée Maillol in a handsome remodeled 18th century building in the heart of Paris, where the sculptor’s work, including bronze studies of her young, Rubenesque body in allegorical poses, is on display, alongside works by Rodin, Gauguin, Picasso and Valadon from Vierny’s priceless private collection.

Two girls who modeled for Balthus—one who became his lover when she was sixteen, the other the eight-year old subject of his Polaroid studies—went on to have distinguished careers, not as artists but in a field perhaps directly related to Balthus’s disquieting oeuvre; one became a psychoanalyst, the other a psychotherapist.

Françoise Gilot, Picasso’s only muse who got away, has lived well too, defying his predictions and his attempts to block publication of her best-selling memoir. She is now 98 and enjoyed a long and happy marriage—to a scientist rather than an artist. Although Picasso attempted to dissuade galleries from buying her work, she has flourished as a painter and continues to exhibit her work internationally.

There is no sign of rancor in Celia Paul’s quiet memoir. After she and Freud parted in 1988, she continued to paint—haunting, ethereal portraits of her mother and sisters, her work a whisper to Freud’s roar—in the studio he bought for her overlooking the courtyard of the British Museum. Nine years ago, she married the philosopher Steven Kupfer; though they are evidently devoted to each other, she chooses to live alone in her studio. Paul’s life is her work and in its pursuit she strives daily to make one pure, truth-telling mark on an imperfect world, handmaiden now to her own creative impulse.

In 2012, the year after Freud died, she produced her version of “Painter and Model,” referencing Freud’s 1987 portrait. As in his picture, she depicts herself barefoot, the floor of her studio is littered with discarded tubes of paint and the dress she is wearing is encrusted with pigment. But there is no naked man, she is alone, her eyes are averted from the artist—herself—and her brow is furrowed in an expression of profound sadness. “The mood is sombre,” she writes of the picture, “and the colours, slate-grey and mother-of-pearl, have an affinity with Gwen John, as well as sharing something of her interiority. I am like her. . . both painter and model.”

__________________________________

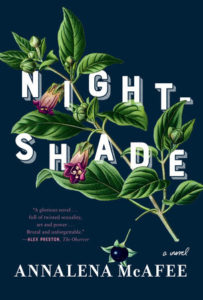

Nightshade by Annalena McAfee is available via Knopf.

Annalena McAfee

Annalena McAfee was born in London and was educated at Essex University. She is the author of Hame and The Spoiler. McAfee worked in newspapers for more than three decades. She was arts and literary editor of the Financial Times and founded the Guardian Review, which she edited for six years. She lives in Gloucestershire with her husband, the writer Ian McEwan.