What Accounts for the Lasting Appeal of Dune?

Michael Dirda on the Perennial Resonance of Frank Herbert's Masterpiece

Arrakis, the desert planet sometimes known as Dune, is the only place in the universe where melange can be found. When ingested regularly, this expensive and addictive spice yields a remarkable effect—it can prolong a human life by two to four times the normal span. In special cases, even longer. Mining ‘spice,’ however, is not only difficult but also exceedingly dangerous, mainly because the operations attract gigantic, voracious sandworms, some as long as four hundred meters. Nonetheless, the Baron Vladimir Harkonnen has brutally exploited Arrakis and its people for years, thus acquiring a sizeable fortune to underwrite his own outsized ambitions, which may extend to the Imperial throne itself.

Even now, half a century since it first appeared in 1965, Dune is certainly still “the one”—it continues to top readers’ polls as the greatest science-fiction novel of modern times. Many would say of all time. Before Star Wars, before A Game of Thrones, Frank Herbert brought to blazing life a feudalistic future of relentless political intrigue and insidious treachery, a grandly operatic vision—half Wagner, half spaghetti western—of a hero discovering his destiny. Characters include elite samurai-like warriors, sadistically decadent aristocrats, mystical revolutionaries, and, not least, those monster worms, which barrel along under the desert surface with the speed of a freight train, then suddenly emerge from the sand like Moby Dick rising from the depths.

Frank Herbert (1920-1986) was approaching forty when he began to work on Dune. Although he had published a handful of stories and, in 1956, one excellent novel of psychological science fiction (The Dragon in the Sea, also known as Under Pressure), he mainly earned his living as a journalist, for a while as night photo editor at the San Francisco Examiner. Over the years he also composed speeches for Washington politicians, took on freelance writing assignments, and unsuccessfully submitted fiction to well-paying magazines such as The Saturday Evening Post. As late as 1962 Herbert’s science fiction brought in so little—only a few hundred dollars a year—that he relied on his wife Beverly to take part-time jobs while caring for their two sons. Middle-aged and frequently in debt, Herbert must have sometimes felt himself to be a failure.

Even now, half a century since it first appeared in 1965, Dune is certainly still “the one”—it continues to top readers’ polls as the greatest science-fiction novel of modern times.

Still, like many good journalists, he always possessed boundless curiosity, reading widely in history, science, and anthropology—J. G. Frazer’s The Golden Bough was a favorite book—and, in the 1950s, actually learning enough psychology to practice, briefly, as a lay analyst. Literature being another mode for exploring the intricacies of human character, Herbert gradually found himself thinking more and more about what Joseph Campbell called “the hero with a thousand faces.” C.G. Jung and Lord Raglan had established the recurrent elements of almost any hero’s life cycle: a birth surrounded by mystery, evidence of special gifts, exile in the wilderness, conquest of a monstrous beast, a near-death experience followed by the assumption of a new identity, and finally a triumphant victory over old enemies before an enigmatic disappearance and subsequent apotheosis. From his research, this enthusiastic student of comparative religion also knew that Judaism, Christianity, and Islam were all originally desert religions, founded by prophets whose lives conformed to the hero archetype. Closer to home, the harsh survivalist culture of the indigenous peoples of North America, especially the Inuits, had long fascinated Herbert and, as a frequent visitor to Mexico, he had grown aware of sacred Indian rituals, which often included the use of consciousness-altering drugs. All these would contribute to the creation of Dune.

There were, obviously, more literary influences as well. Like any post-World War II science-fiction fan, Herbert was familiar with Isaac Asimov’s Foundation Trilogy, then widely regarded as the greatest imaginative work in the genre. First published as a series of stories during the 1940s, it chronicles a galactic civilization’s political crises and the secret machinations of a hidden sect. The Broken Sword (1954), a superb heroic fantasy by Herbert’s good friend Poul Anderson, may have provided additional inspiration. Set alternately in an iron-age England and a decadent Faery, the novel is a thrilling, if bleak, saga of ambition and revenge, told from multiple points of view, featuring prophecy, murderous betrayals, ecstatic visions, and tragic romance. Another close writer-friend, Jack Vance, was already, and rightly, celebrated for his unrivaled genius at creating rich and complex alien civilizations. Many of Vance’s books track a young man’s adventures as he masters the ways of a strange planet.

Nonetheless, wide reading in anthropology and history, a preoccupation with the myth of the hero, and several powerful literary models weren’t quite enough to generate the big book Herbert wanted to write. Something more was needed. One day in 1957 he learned about a government program designed to control sand dunes in the Pacific Northwest. It sounded as if it might make a good magazine article. Instead, six years later, Herbert mailed a hefty typescript to John W. Campbell, the most celebrated of all American science-fiction editors, then at the helm of Analog magazine. Campbell serialized the book in seven segments—the first three entitled “Dune World” and the last four “Prophet of Dune”—between December 1963 and May 1965.

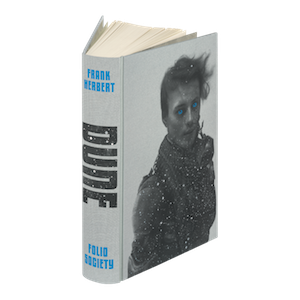

In the annals of publishing there are many tales of idiotic misjudgments, but few can match this one: twenty-three book publishers rejected Dune. It was too long. It was too demanding. It was too philosophical. And its cover price would be too high because of its length. Fortunately, the writer Sterling E. Lanier—whose stories about Brigadier Ffellowes rival the delightful club tales of Lord Dunsany’s Joseph Jorkens—was then employed as an editor for Chilton, purveyors of heavy-duty automobile repair manuals. (I myself once owned the Chilton’s volume for the 1966 Chevrolet Impala.) Lanier offered $7,500 for Dune. The print run for the 1965 first edition consisted of just 3,500 copies, and 1,300 of those were pulped because of misprints. Reviews in mainstream media were mixed at best, and Chilton didn’t need to reprint the novel until 1968. While originally priced at $5.95, a fine first edition of Dune might today cost you $10,000. One signed by Herbert would go for considerably more, perhaps as much as $20,000.

In 1965 Dune won the Nebula Award (voted on by fellow science-fiction writers) and in 1966 the Hugo (voted on by fans). Like Robert Heinlein’s roughly contemporary Stranger in a Strange Land (1961), Herbert’s masterpiece initially garnered its most enthusiastic audience on college campuses. There it gradually came to be revered as the first major work of ‘ecological’ science fiction, a touchstone for the socially responsible use of natural resources. In due course, the book’s growing popularity led to a film, directed by David Lynch, which appeared in 1984 to scathing reviews and embarrassing box-office earnings. (Its kitschy grotesquery and baroque excesses have since made it a cult favorite.) By then Herbert had added several further installments to the Dune chronicles; the third, Children of Dune (1976), became the first science-fiction hardcover to make the New York Times best-seller list. Even the author’s death, at sixty-five from pancreatic cancer, didn’t stop the Dune juggernaut: to this day Herbert’s son and biographer, Brian, and co-author Kevin J. Anderson continue to add many subsequent volumes to the Dune cycle.

Much of the book’s power derives from its very inconclusiveness, from what it hints at but never quite spells out about the past and the future.

Still, none of these later works, however much they may deepen or complicate Herbert’s original vision, is a match for the moving grandeur of the book you now hold in your hands. What accounts for the lasting appeal of Dune? Some of its power certainly derives from the novel’s artful structure. For instance, nearly every chapter opens with an apposite quotation from the memoirs or writings of the Princess Irulan, thus enlarging the temporal scope of the action: this isn’t just story, this is history (or at least myth-making). In the brisk manner of newspaper reporting, Herbert employs very short paragraphs, sometimes of only two or three sentences, thus ensuring fast movement to the narrative.

With few exceptions—the thoughts and hallucinations of a man dying of thirst, the psychedelic visions that accompany a deadly drug—he seldom indulges in poetic prose or lengthy descriptive passages. Instead, each chapter presents an intense, dialogue-rich mini-drama, whether an elegant dinner party or a strategic council meeting, a Fremen religious ritual or a duel to the death. To thicken his narrative polyphony further, Herbert often inserts, in italics, the unspoken thoughts of one or more of his major characters. These typically run counter to what that person is actually saying. What is more, the forward action is radial as well as linear—we mainly follow Paul’s adventures, but these alternate with glimpses of Baron Harkonnen’s vicious homelife and episodes spotlighting Lady Jessica, Thufir Hawat, Gurney Halleck, and the eunuch-emissary Count Fenring. Eventually, of course, all the various plot-lines explosively converge.

While there are numerous surprises in Dune, as well as considerable irony, there is no humor at all. For all its excitement and vitality, the novel is pervaded with a tragic sense of life. In the words of one character, ‘No more terrible disaster could befall your people than for them to fall into the hands of a Hero.’ In particular, the more psychically sensitive—Paul, Lady Jessica, the Reverend Mother, the mysterious child Alia—are troubled, even convulsed, by prescient visions, not just of future warfare but of bloody and endless jihad. For every path taken or not taken, there are consequences; for every choice, there are losses as well as gains. There are no final victories.

All but the greatest science fiction tends to date after a couple of decades. The Foundation Trilogy itself now often comes across as pulpy space opera. Yet Dune has largely escaped that fate. Apart from the homosexual Baron Harkonnen, who risks being an agglomeration of gross stereotypes, the book’s characters, action, and concerns still resonate in the 21st century. Its women are as tough, capable, and self-reliant as its men, while Paul’s various ordeals and self-explorations connect him to a deeply feminine racial consciousness. Thematically, the novel shows us religious extremism in action, the dire consequences of a single-product economy (for ”spice,” read “oil”), the crucial need for global ecological planning, and the dangers of genetic manipulation, as well as, to speak more philosophically, the frequent hollowness at the heart of all our lives. Even those who acquire paranormal insight and knowledge quickly discover that the gift brings them little but pain and sorrow.

Frank Herbert’s masterpiece is more than a futuristic swashbuckler or a science-fiction ”coming-of-age” novel (Paul is still in his teens when the book ends). It is a serious moral fable about the foreseen and unforeseen consequences of the choices we make. With his usual wisdom about such things, Chekhov once said that only a god could distinguish success from failure in life without making a mistake. Sometimes, Dune reminds us, even a god might not be sure.

______________________________________________________

Excerpted from the introduction to Dune. Used with the permission of the publisher, The Folio Society. Introduction copyright © 2021 by Michael Dirda.

Michael Dirda

Michael Dirda is a Pulitzer Prize-winning literary journalist, a weekly books columnist for the Washington Post, and the author of five collections of essays: Readings (2000), Bound to Please (2005), Book by Book (2006), Classics for Pleasure (2007) and Browsings (2015). He has also written the memoir An Open Book (2003) and On Conan Doyle (2012), which received an Edgar Allan Poe Award from the Mystery Writers of America. His current project is a reconsideration of popular fiction during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. He has written introductions to The Great Gatsby (2013), Dune (2016), East of Eden (2017) and Atlas Shrugged (2018) for The Folio Society.