Weird Fiction: A Primer

On the Heirs of Kafka and Borges

It is perhaps appropriate that weird fiction, like so many of the beings and landscapes that populate it, eludes easy description. Is it a genre or an aesthetic? Does it represent a new literary evolution or a revival of underrated styles from a century ago? Sofia Samatar’s World Fantasy Award-winning novel A Stranger in Olondria is at once a deeply felt character study, a description of a world similar to (but clearly not) our own, and an unconventional ghost story–compelling work that occupies a host of categories. For her, weird literature is “speculative fiction with a complicated relationship to genre. It might blend genres or overturn their conventions, while still remaining clearly anti-realist.” When asked about it, she pointed out that the earliest examples of the form “predate the marketing categories of fantasy, science fiction, and horror.”

JS Breukelaar’s debut novel American Monster encompassed aspects of science fiction and horror and filtered them through a surreal lens; she described her next novel, Alethia, as “part ghost story, part crime novel.” Her first exposure to weird fiction came through the movies; she cited in particular “The Wizard of Oz, Jane Eyre, but also Pan’s Labyrinth, [The] Never-Ending Story, Cronenberg, Kurosawa…” For Breukelaar, the importance of weird fiction is less about defining it and more about what it does. “Firstly, through character, weird fiction represents the desire for or pursuit of some hidden principle beyond the mundane,” she said. “[C]onnected to this, is a temporary, maybe, abolition of the rational rendered both estranging and deeply seductive at the same time.”

Some of the recent attention trained on weird fiction can be attributed to Jeff VanderMeer. His acclaimed Southern Reach trilogy shows off weird fiction’s range, encompassing elements of science fiction, Lovecraftian terror, paranoid conspiracy thrillers, and body horror. He’s written about literature as it relates to the first season of True Detective, and has acted as an advocate for authors who deserve a wider audience, including Michael Cisco and Thomas Ligotti. His work as an editor includes (in collaboration with his wife Ann) The Weird: A Compendium of Dark & Strange Stories. (The two also founded the site Weird Fiction Review, which “exists in a symbiotic relationship” with the periodical Weird Fiction Review, edited by H.P. Lovecraft biographer S.T. Joshi.) The Weird is stun-your-enemies huge: over 1,100 pages in length, and covering over a century’s worth of fiction. Its afterword is by China Miéville, whose generally indescribable fiction has also helped raise the profile of weird fiction.

Cameron Pierce, author of a number of surreal and sometimes horrific stories and novels, and the head editor of Lazy Fascist Press, cites The Weird as a great place to get the shape of what weird fiction encompasses. He called the VanderMeers’ anthology “definitive,” and said that a full view of the history it contains shows “how Franz Kafka and Bruno Schulz and Lovecraft all eventually lead to writers like Michael Cisco and Brian Evenson.” Pierce is also deeply involved in the world of Bizarro fiction, which shares something of an overlap with weird fiction. Breukelaar noted that she admires “writers like Jeremy Robert Johnson and Cameron Pierce and J David Osborne and Seb Doubinsky for the way they worm bizarro elements into flesh-and-blood characters.” And Pierce commented that, “[s]ome bizarro fiction, though far from all of it, derives from weird fiction DNA. Cody Goodfellow, Molly Tanzer, and Jeremy Robert Johnson are three visionary, deeply original writers who are pushing bizarro into weird fiction territory.”

Elsewhere, more traditionally literary journals have also published a fair share of weird fiction, with Tin House and Conjunctions both taking leads in balancing impressive craft with surreal stories and imagery. Breukelaar cited the influence of the Tin House anthology Fantastic Women on her; after being given a copy by editor Rob Spillman, she said, “I’ve devoured everything by Kelly Link, Karen Russell, Lucy Corin, [and] Aimee Bender since.”

Certain authors loom particularly large in weird fiction’s history: notably, Franz Kafka and Jorge Luis Borges. Samatar cited Borges as the first author of weird fiction she encountered, adding that at the time that she read him, “I wouldn’t have described him that way. I didn’t have the term yet.” From Borges, one can trace a line of literary influence to the likes of Steven Millhauser, Neil Gaiman, Kelly Link, and Norman Lock, all of whom have written work that doesn’t fit easily beside other fiction.

The five books that follow suggest the breadth of what can be considered weird fiction. These novels shift in unpredictable ways, bridging genres and styles at a moment’s notice, and tell deeply compelling stories that nonetheless confound expectations. Call it singular, call it surreal, or opt for a classic: call it weird.

William Hope Hodgson, The Night Land

William Hope Hodgson is often cited as one of the first writers to create work that’s recognizable as weird fiction. His 1908 novel The House on the Borderland was cited by Pierce as one of “the best early weird fiction novels,” and was adapted for comics in 2000 by acclaimed horror artist Richard Corben. The Night Land has H.P. Lovecraft and China Miéville among its admirers. It is also a deeply strange work of fiction: a kind of quest narrative set on a far-future Earth, where massive pyramids house most of humanity, telepathy is common, and volcanic landscapes abound. To top that off, it’s written in an oddly Biblical style: the Book of Revelations meets pulp adventure meets cosmic horror.

Samuel R. Delany, The Einstein Intersection

In one sense, Samuel R. Delany’s The Einstein Intersection is a science fictional retelling of the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice. And one wouldn’t be wrong to suggest that it succeeds as exactly that: it won the Nebula Award for Best Novel in 1967, after all. But for all that it has an easy elevator pitch, the actual details of the story are much more surreal. The human-seeming characters, for instance, are actually aliens who have settled on an abandoned Earth and altered their forms; their mythology borrows from what we might think of as classics, but also incorporates fragmented and half-remembered pop culture detritus. Throughout, the novel runs amok with expectations, repeatedly bringing together the ancient and the futuristic to create something entirely new.

Leonora Carrington, The Hearing Trumpet

Leonora Carrington’s commitment to the strange extended far beyond her prose, of which The Hearing Trumpet is probably the most notable example—she’s best known for the artwork that she made over the course of her long life. The Hearing Trumpet is far from the only notable work that she did in the medium; her story “White Rabbits” was included in the VanderMeers’ The Weird. The Hearing Trumpet is about an elderly woman whose family sends her off to a home; soon, she discovers strange happenings afoot, which rapidly proceed from the mystical to the apocalyptic. The nonchalance with which Carrington’s narrator navigates an increasingly irrational world is abundantly charming.

David Ohle, Motorman

Artificial hearts, multiple suns, and phantasmagorical landscapes all factor in to David Ohle’s decidedly visceral novel Motorman. There are certainly elements of dystopian fiction in here, but the sense of oppression takes on an increasingly unhinged level of irrationality. Ohle is both playing with and undermining classical fictional narratives here; one can see the basic blueprints of the work even as the imagery itself eschews neat borders. “It’s a gnarly place where anything can happen,” Ohle said about this fictional world in a 2014 interview at BOMB. And his affection for it is clear: Ohle has returned to it in several novels since Motorman’s 1972 publication, including The Age of Sinatra, The Pisstown Chaos, and last year’s The Old Reactor.

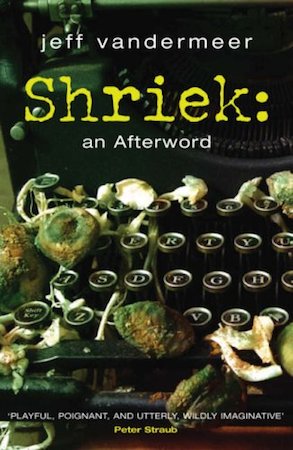

Jeff VanderMeer, Shriek (An Afterword)

Jeff VanderMeer’s Shriek (An Afterword) is one of the three books that he’s set in the fictional city of Ambergris—a sometimes (literally) hallucinatory place that allows for everything from tales of espionage and intrigue to stories of warring publishing houses to accounts of unspeakable ailments. (Paul Bebergal’s review for The Believer began, “It’s not clear what obsesses Jeff VanderMeer more, mushrooms or books.”) In Ambergris, fungi frequently infect and transform the residents, a condition that’s at the heart of this novel. Shriek (An Afterword) is a annotated narrative in which those annotations spiral from the main narrative and create even more tension, a meditation on what it means to change from human to something else, and a surprising tale of sibling rivalry and affection. The joy and terror of the Ambergris books is their ability to juxtapose the familiar with the alien; it’s a magnificently beguiling and unpredictable read.

The featured image is a detail of Scott Eagle‘s painting for the cover of Jeff VanderMeer’s book, City of Saints and Madmen.

Tobias Carroll

Tobias Carroll is a writer and essayist, and the managing editor of Vol. 1 Brooklyn. He is the author of three books: Political Sign (Bloomsbury), part of the Object Lessons series; the story collection Transitory (Civil Coping Mechanisms) and the novel Reel (Rare Bird).