We Were Cyborgs: On the Construction of the Self As a Teenage Girl

Olivia Gatwood Explores Conforming to Beauty Standards in the Age of Artificial Intelligence

It all started in the fluorescent food court at Winrock Mall in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Whitney and I were hunched over paper plates, licking school bus-yellow cheese from the center of our Hot Dogs on a Stick. “You’ll need new jeans,” she said, eyeing the zip-off cargo pants I’d stolen from my brother. “And do you own anything from Hollister?” I had never heard of Hollister, but by the end of the day that dusky, sweet pea perfume cloaked corner of the world would become my Holy Grail, the zenith I would bushwhack towards for years to come.

As girls landlocked by desert, the surf-themed clothing store was the closest we could get to saltwater. Or the closest we could get to a kind of beauty that seemed natural to girls in Southern California: honey-colored waves and hairless thighs, surfboards wedged between their ribcages and biceps. Whitney ran her hand down my forearm. “At least you have this.” She was talking about the tan I’d developed. Little to my knowledge, this trait would become the most enviable thing about me. Eventually, someone would even start a rumor that I had a tanning bed in my living room.

What I thought was an allegory for my past, had become the reality of my present.But the reality was far more disappointing. Very simply, I had been in the sun. For the last three years, I had been living in Port of Spain, Trinidad—the southernmost country of the Caribbean—where my mother had taken a job in public health. The last time I was an American resident, I was a child, only ten years old, with almost no understanding of beauty or desirability. As I came of age in Trinidad, I adapted to the social culture around me which, in the early aughts with no social media, meant we were almost entirely severed from American trends. Just as I had begun to feel as though I’d found my bearings in Port of Spain—I had a friend group, a first boyfriend, a fluency in local slang—we were back on a plane to New Mexico. So there I was, in the food court of Winrock Mall, gradually realizing that if I wanted to thrive in the social hierarchy of an American middle school, I would need to renovate my identity from the ground up. The only problem? I couldn’t afford to.

Whitney and I left Hollister empty handed that day. As we waited for the bus home, she comforted my disappointment, explaining that she didn’t expect us to buy anything, she just wanted me to see it. That was the most important part. There were ways of acquiring beauty other than buying it. The first step is knowing what it looks like, so that you can replicate it.

Over the course of the next year, I studied the girls around me with an unwavering scrutiny. What I learned was this: if you couldn’t afford beauty, you had to build it, and in order to build it, you had to be scrappy. I was not alone in my inability to afford braces or a dermatologist or a fifty-dollar polo shirt. I was just late to the game. But once I understood how to play, I became a We, and we were in a rat race. What we didn’t inherit, we could create. What we didn’t know we could learn. What we didn’t own, we could steal.

We taught ourselves how to cut our bangs and whiten our teeth and alter our clothes. We stirred sugar into our face wash and squeezed lemon juice into our hair and pierced our belly buttons with sewing needles. We knew which department stores had no security cameras and how many thongs could fit into a back pocket without an obvious bulge. We hovered in pharmacy magazine aisles, or Planned Parenthood waiting rooms, or the lobbies of our mothers’ salons, scouring the pages of Elle and Vogue and Shape, publications to which we could not afford a subscription, frantically collecting tips and tricks, advice that enabled us to invent the beauty we did not see.

We claimed we were born with certain traits, just to avoid disclosing how we’d achieved them. We spied on one another, rooted through each other’s bathroom cabinets, and, in turn, lived in a constant state of paranoia that what we knew was always at risk of being taken, and with it, our beauty would be taken too. We dug through racks at the second-hand store searching for last season brand name tops and skirts. We bleached the yellowed armpits and prayed that it did not belong to a girl at school who would recognize her trash on our bodies.

Of course, there were girls who didn’t have to play. The ones who could afford the hair straightener that reached 480 degrees. Or the ones who had a direct and unlimited source of information from their former beauty queen mothers. While the rest of us were fighting over ripe produce in the grocery store, these girls had an orchard in their backyard. But we, the third rank, had technical skill.

We were cyborgs, made up of the world’s hand-me-downs and each other’s stolen parts; girls who wanted to look like other girls while desperately attempting to look like no one and, in turn, all looking the same. We were constantly tinkering with our prized machines in the tool sheds of our bedrooms. We were rewarded for our work. We accepted trophies in the form of flirtation and freebies and false A’s on failed tests. We all had the same goal: for our beauty to be the first thing anyone noticed.

After all, it was the first thing we noticed about everyone else. We lived in the oscillation between hate and envy and desire for one another. We were always watching. In fact, we preferred any vantage point that offered a little bit of distance from one another—from the bleachers, or across the locker room, or behind the lens of a point and shoot camera—because it meant we could just watch one another. That’s how it all started, anyway.

Over time, the seams of our quilted bodies blurred. We evolved from chimeras to our own species; we became accustomed to our limbs—movements that once felt unnatural and janky eventually were practiced enough to seem inherited from birth. We began to splinter off into different worlds, different identities. We lost interest in one another—we got boyfriends, we got depressed, we got into college. But we could never really forget that we had created each other.

Sure, we had become individuals, but our mannerisms remained identical. We had conditioned ourselves to sneeze with the same polite squeal. We had bullied our once boisterous laughs down into palatable giggles. One girl was a ballerina and we liked the way she walked, with her toes pointed out, and soon we all walked that way. We continued to walk that way, down the hallway and past one another, barely exchanging glances. We were all ballerinas. People asked if we were sisters, even after we’d stopped speaking to one another. We took the fact of our resemblance as both a compliment and an insult.

The year we graduated high school, a group of cheerleaders in upstate New York developed a case of contagious tics and seizures. At first, everyone in the town assumed it was fake. Then, they feared it was something in the water. In the end, the diagnosis was mass psychogenic illness—in this case, a chronic desire to belong that eventually translates into physical behavior. In most examples of this phenomenon, the person exhibiting such behavior has no control over whether or not they do it. But the illness—the validity of which is still heavily argued in the field of psychology—is far more common in young women, especially those who are in tight-knit social groups with a clear hierarchy, like cheerleaders. Often, the first symptoms begin with whichever girl is at the top.

As I grew older, moved away, I resented how much of myself was not my own. I felt like the years I should’ve spent learning who I was, I actually spent learning how patch together a version of what I should be. And because of that, I had no sense of how to actually define myself without help. Being away from the girls I grew up with meant I was unmoored; I was free but without a compass, I didn’t even know where to begin. I wandered aimlessly around clothing stores, unsure what I was even looking for. I left my face bare, cut my hair blunt. I avoided my own reflection because she felt unfamiliar. She didn’t look like anyone I knew.

I felt lonely and unclaimed. I found solace at the Brooklyn Public Library, where I could bury myself in other people’s stories and forget for a moment that I had an identity at all. I spent hours locked in the studio apartment I shared with my boyfriend, working my way through whatever stack I’d checked out that day. I became obsessed with stories about A.I., particularly those in which the robot is presented as a real woman.

These fembots were supposed to represent the opposite of humanity, but what I saw was a profoundly accurate depiction of how I felt back then: a girl who had been constructed, built with mismatched parts to ultimately become the most consumable version of herself. I saw myself in the trajectory of a fembot being released into the real world and not knowing who or where she was. I read every book, watched every film about fembots that I could get my hands on, because they felt like only women characters I actually understood. But then, when I finally looked up from the pages, what I thought was an allegory for my past, had become the reality of my present.

What I came to realize through writing was that she was still inside me, clawing to get out, and that it was up to me to free her.I scrolled through my phone and watched as the faces looking back at me began to resemble robots more than human beings. I saw certain features become trends; Instagram influencers operating like machine learning engineers, taking the most ideal parts of what has already existed and merging them into one, ideal face—either through surgery or filters or both. And when this ideal face was released into my feed, I would watch as it subsequently multiplied, as those who consumed it attempted to replicate and showcase it in our own ways. From this repeated process, a new face would eventually emerge. A new beauty standard, which has been almost entirely dictated by an algorithmic gaze.

In an essay for the New Yorker, writer Jia Tolentino coined the term, Instagram Face, referencing how this gradual pattern of synchronized personal editing has resulted in a “single cyborgian look.” Possessed by young—mostly white—women on the platform, it is a face that often obfuscates ethnicity by way of collecting features from women across varying identities. The face, whether I wanted it to or not, became intrinsically connected to my understanding of beauty, even though I never actually met a real woman who possessed it. Perhaps it would be too uncanny, seeing the face on the subway or at a restaurant. Perhaps it only exists in a dimension we can witness from afar. A place we can’t reach, only yearn for. A place just close enough that we can study it, and then figure out what to replicate.

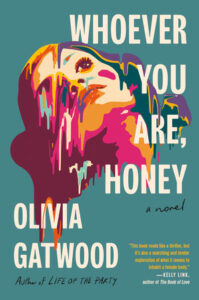

As the world around me progressively felt less human, I sought shelter by working on my first novel, Whoever You Are, Honey. I was asking myself this question: what would it feel like to spend the day with a woman—a fembot or an Instagram Face—whose beauty had been meticulously constructed from the ground up? What would I, as a woman, notice that a man wouldn’t? What kinds of questions would we ask one another? And what would she feel like, standing across from me? I went into the story thinking I would obviously relate most to the protagonist, Mitty, a woman whose humanity is arguably too real; whose messy past and ugly memories make up almost the entirety of who she is.

But as I began to write Lena, the woman across from Mitty, who feels altogether disconnected from who she is and who she has been, who is concerned that her entire personhood has been built by someone else, I saw myself so clearly. I thought I had long since severed myself from the junkyard chimera I was all those years ago, but what I came to realize through writing was that she was still inside me, clawing to get out, and that it was up to me to free her. I needed to give her the ending she deserved.

Whitney came to visit me recently, in the small town where I live with my partner and dog. We are both professional artists. We both make a living attempting to merge fragments, whether it be words or images, into something sensical and beautiful and entirely original. We work within the context of history while also trying to say something new. We are so different. But occasionally, she will do something—twist her dark curly hair into a braid or laugh at a joke someone else makes—and I will see myself. I will see my mannerisms. I will see what she taught me. Or, what I taught her. I can’t remember who started it.

__________________________________

Whoever You Are, Honey by Olivia Gatwood is available from The Dial Press, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.