“We Want to Make It Feel Like a Party.” On the Transformation of Southwest Review

A Lit Mag Embraces Colorful Design and Literary Translation

In the past five years a magazine from Dallas, Texas, has made a small but palpable stir in the world of literary journals, publishing stories, poems, and essays by some of the most exciting writers from several Latin American countries, including Ecuador, Mexico, Bolivia, and Colombia, in addition to some extraordinary voices from the United States. Southwest Review, for anyone paying attention, has become exciting.

If dedicated readers of contemporary fiction and poetry were asked, say, who’d recently published an essay by Roberto Bolaño’s archivist, or stories, essays, and poetry by esteemed authors of books published by Graywolf Press, New Directions, Catapult Books, Coffee House Press, Seven Stories Press, Charco Press, and others, they may suspect The Paris Review or The New Yorker. Yet, they’ve all appeared in a nonprofit quarterly based in Dallas, Texas, which also happens to be the third-oldest continuously published literary review in America.

To be completely forthright, I’ve had the pleasure of working personally with Southwest Review over the past few years, getting stories accepted and published as well as enjoying a “cover reveal” for my second novel. Their insights, attention to detail, and open-minded editorial feedback have always been a pleasure. Writing this piece was simply a writer’s enthusiasm for a small and singular literary magazine and what they’ve been doing.

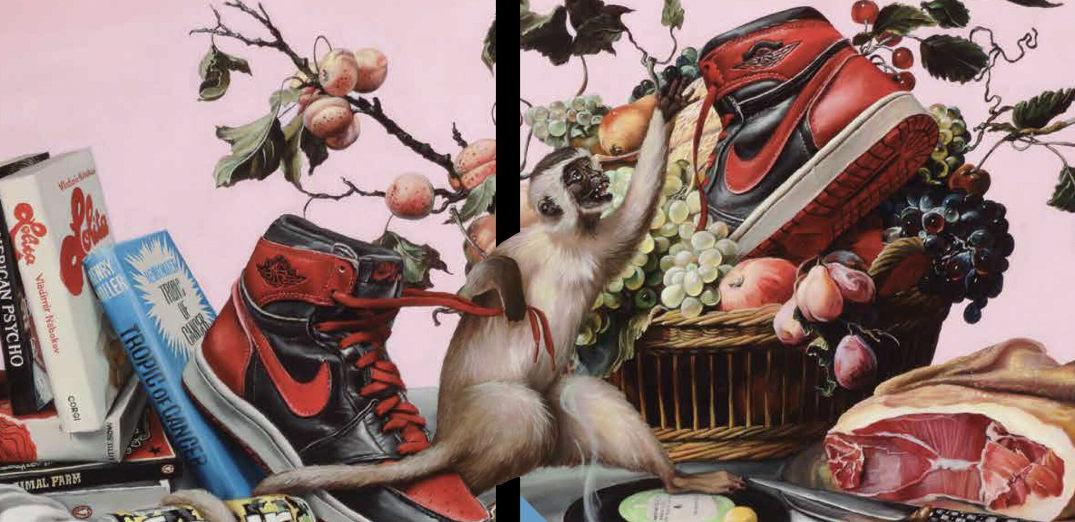

Founded in 1915 and housed on the campus of Southern Methodist University, Southwest Review has, of late, gathered a remarkable energy, evident in the electric, eclectic, whimsical, and downright envelope-pushing issues which have been published with impressive consistency. The cover designs are bold, bright, eye-popping, and fearless, emblematic of the work inside. Over the past few years something has happened, a shift in the design and aesthetic, in the enthusiasm and, perhaps most importantly, the curation.

For a literary journal old enough to have great-great-grandchildren, looking forward while embracing the past can be a precarious proposition. As Ben Fountain wrote in 2015, celebrating the journal’s 100th birthday: “The roll call of heavyweights who’ve appeared in its pages stands up to any American magazine, large or small, of the past 100 years.” Such a history might be a burden to many, but Southwest Review navigates it deftly, making it look easy.

The lauded list of its authors—ranging from Allen Ginsberg, Anne Carson, Robert Penn Warren, Orhan Pamuk, Annie Dillard, and Saul Bellow—has seamlessly shifted to names like Julián Herbert, Chloe Aridjis, Claudia Piñeiro, Juan Pablo Villalobos, and Valerie Miles. “As stewards of a venerable institution that dates back to 1915,” says Editor-in-Chief Greg Brownderville, “we’ve inherited a rich history, and we have a responsibility to uphold that legacy. At the same time, while we celebrate our past by doing things like designing a broadside for Larry McMurtry’s first-ever published piece—which appeared in our winter issue of 1960—we like to keep it fresh and fun.”

This idea of fun pulses through its issues, with cover designs by art director Julie Savasky who, Deputy Editor Robert Rea notes, is “the guiding hand behind our visual aesthetic.” Indeed, this marriage of “serious literature” paired with a playful self-awareness is evident everywhere; in recent issues a reader was just as likely to find a pair of sunglasses inside as a Roberto Bolaño bumper sticker. There appears to be an unspoken ethos which states: playful and literary are not mutually exclusive. A somber, serious, minimal design is nowhere to be found; instead, colors jump out, vibrant and warm, colorful and attention-grabbing, influenced no doubt by contemporary art and even comics. “Too often the scene as a whole makes literature feel like homework,” Rea says. “We want to make it feel like a party.”

This goes beyond the physical quarterly; in addition to the publication of essays, interviews, stories, and poems, Southwest Review also has a vibrant website and blog, including a monthly movie column, I Wake Up Streaming, by novelist William Boyle, and a pop music column, Make Love in My Car, by poet and memoirist Kendra Allen.

Having been a bookseller (and a reader) in Texas, I felt an immediate connection to what I saw SwR becoming; a publication in dialogue with Texas, the border, the United States, but not solely, as if, by looking inward, the magazine knew it needed to embrace and celebrate voices from home and abroad. Southwest Review is a Texas publication but it’s no less a national and an international one; this bridge between cultures is nowhere more evident than its content and visual presentation.

A typical issue of SwR shows the love, passion, and dedicated work that supports a belief in voices from around the world, giving the impression of an artistic liaison between borders, cultures, and languages. Work by U.S. writers like Mary Miller, Bud Smith, and David Leo Rice share pages with writing in translation by some of the leading names in Latin American literature.

Translators have as much of a hand in the work as the authors, their names placed prominently among the contributors. “We didn’t know a single translator when we got started,” says Brownderville, “but over time we’ve gotten to know an incredibly talented team of translators—Will Vanderhyden, Frances Riddle, Robin Myers, Lizzie Davis to name-check a few—who influence our editorial decisions as much as any other writers. So much so that we’ve created positions for in-house translation.” Indeed, legendary translator Christina MacSweeney sits on the magazine’s advisory board, and translator Sarah Booker is an editor.

Brownderville and Rea understood moving Southwest Review into new territories would be a challenge but one that both relished. “We knew we wanted to put our own spin on things,” says Rea. “We also knew we wanted to include Latin America in what we were doing.” The horror-themed fall issue of 2022 was guest-edited by Ecuadorian author Mónica Ojeda and translator Sarah Booker. In a move both adventurous and unique, SwR welcomed submissions in Spanish and translated the accepted work in-house. This shows a serious commitment and vision: Southwest Review isn’t merely publishing works and translations from other countries, but building working relationships, partnerships, even friendships. Moreover, these partnerships carry themselves into the masthead: the advisory board, which includes novelist Rodrigo Fresán and Carolina Orloff, a translator and the publisher of Charco Press, is a veritable United Nations, boasting names from the UK, Barcelona, and the American South.

I find myself returning to the word “fun” when writing about Southwest Review but it’s because it feels that way—like a celebration.This openhearted attitude says as much about Texas, a state whose border is shared principally with Mexico (often the physical and cultural bridge to the rest of Latin America) as the current literary landscape. In this instance, Dallas, host city of the Hay Festival Forum for the past six years, a global, three-day literary event celebrating Spanish-language literature, consisting of panels, concerts, and more. Literature in translation is not in short supply: Dallas-based Deep Vellum, an award-winning publisher of international literature, just celebrated its tenth anniversary. The Wild Detectives, an independent bookstore and bar in Dallas (also, incidentally, one of the hosts of the Hay Festival), takes its name from a Bolaño novel. “Obviously Hispanic America is vital to the culture of the Southwest,” explains Rea, “and when we took over from the previous editors—this was in 2018—MAGA xenophobia was in full swing and Trump had been characterizing Latin Americans as criminals, rapists, and whatnot. So eventually we landed on the idea of the border as the central metaphor for our editorial vision. We wanted to create a magazine that brings together writers from both sides of the border—as a way of starting a conversation across cultures.”

The conservative, isolationist mindset that Texas is often known for, is only one shade of an enormous, complex state which contains infinite colors. As a bookseller based in Houston for over a decade I found the act of selling books in translation not only easy but a pleasure. Texas readers, like readers everywhere, want books and voices from across the globe. And once a curious reader discovers a memoir by Cristina Rivera Garza, for example, or a novel by Arianna Harwicz, they want more. Translation isn’t a niche or specialty genre of books but shares the landscape with every other book. There’s a reason War and Peace and Don Quixote or, for more recent examples, the work of Haruki Murakami and Elena Ferrante, are in the lexicon of the everyday: translation. As the popularity of this year’s Nobel Prize winner, Jon Fosse, has shown, interest in translated literature is not an anomaly. Southwest Review recognized this years ago and wanted in on the fun, publishing reviews, cover reveals, and interviews with writers from an array of different countries and languages.

I find myself returning to the word “fun” when writing about Southwest Review but it’s because it feels that way—like a celebration. Sure, it contains all the dark and the light, the good and the bad, the love and cruelty that literature inherently incorporates, but it’s a celebration nonetheless.

And though Brownderville and Rea are pragmatic and tight-lipped about imminent issues and ideas, things are in the works: “We have several projects in the pipeline for next year. We can’t say too much because things are still in the early planning stages, but 2024 is going to be a big year for us. Long story short, magazine-ing will be just one of many things we do here at SwR.” As Ben Fountain wrote in his 100th anniversary piece, “By any standard, the Review has been consistently good, at times great, and, on occasion, recklessly brave.” Eight years later, in 2023, it seems the Review is continuing this tradition with gusto.