We Can’t Do It: How Women’s Contributions to Fighting Fascism Were Forgotten

Natasha Lester on the Collective Amnesia Around Women’s Accomplishments After World War II

Featured image courtesy of The National World War II Museum

Have you ever heard of a woman named Lee Miller? She was a renowned model for magazines like Vogue in the 1920s. She learned photography from Man Ray, became his lover and was perhaps his muse. (In fact, she is also the inspiration for the main character of my own novel, The Paris Orphan.) Miller then had a third career as Vogue’s photojournalist, reporting from the frontlines of Europe during WWII. Her life was a bittersweet combination of the extraordinary and the terrible.

Lee Miller documented the US army’s first use of napalm in Saint-Malo, France; she was one of the first women to photograph the horrors of the concentration camps; and she set up a famously denunciatory photograph of herself in Hitler’s bathtub in his apartment in 1945.

You’d think that after having reported so brilliantly on one of the largest and deadliest conflicts of the twentieth century, Miller would have been able to take her pick of journalistic positions once the fighting stopped. Instead, she was sent to Saint Moritz to report on the social season. She was asked to write recipes. The men had returned from the war and stepped back into their accepted roles as workers and providers. As a woman, Miller was confined to writing about things that interested women, no matter that she’d been one of the first photojournalists to march into newly-liberated Paris just a year before.

How must Miller have felt, after photographing on the frontlines for four short years, to then be told she was only needed to write about socialites or how to roast a chicken? Her photojournalism wasn’t only a meticulous documenting of history—her images were those of an artist. But her work was buried so deep beneath a collective amnesia about women’s wartime accomplishments that, when she died, even her son didn’t know what his mother had done during the war.

As soon as the men came home, governments the world over ran propaganda campaigns encouraging women to give up their jobs.

Miller’s atrocious treatment by the world made me realize that I wanted to write about the way women were permitted to accomplish so much during WWII but were then told to give it all up—their independence, their careers, their legacies—as soon as the hostilities ended. I couldn’t fit that story into The Paris Orphan, but I also couldn’t let it—her story, the stories of women like her—go.

I soon stumbled upon advertisements targeted at women over the war and postwar periods. You might have seen some of the war office recruitment campaigns from the time, including the famous Rosie the Riveter “We Can Do It” posters, and others exhorting women to “Be a Marine,” or with headlines stating “So Proudly We Serve.” And women did serve proudly. In those posters and advertisements, they’re depicted holding their heads high, standing tall and confident, looking as if they could do anything. Because they did do everything. They worked in factories. They took photographs on the frontlines of the war. They spied. They were imprisoned and tortured and killed by Nazis.

But as soon as the men came home, governments the world over ran propaganda campaigns encouraging women to give up their jobs. It was the start of a cultural shift that continued for decades, reflected in advertisements showing women on their knees, serving their husbands breakfast in bed beneath slogans such as, “It’s a Man’s World,” as per a particularly egregious Van Heusen necktie example. See also: an Alcoa Aluminum advertisement of a surprised woman holding a ketchup bottle. The headline reads, “Even a Woman Can Open It.” Or a cigarette billboard from 1967 that says, “Cigarettes are like women. The best ones are thin and rich.”

How did women go from being able to join the marines to being on their knees in a man’s world, praised like little girls when they managed to do something as basic as opening a ketchup bottle? How did it hurt women like Lee Miller, who marched across the frontlines in Europe, and who were then told the only jobs they had to do were to keep themselves slim and to write recipes?

Did it make them rage?

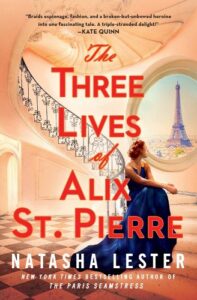

It makes me rage. And that’s why I invented the character of Alix in my latest book, The Three Lives of Alix St Pierre. Alix represents all of the bold, talented women whom the postwar world tried to conquer. She works as a spy for the American government during WWII and then takes a job as the Director of Publicity for the not-yet launched House of Christian Dior. It’s a bold move—she’s twenty-seven, unmarried and, as Nancy White, niece of the infamous Carmel Snow said, “It wasn’t easy working back then…It wasn’t right to work.”

How did women go from being able to join the marines to being on their knees in a man’s world?

Right through the 1960s, women who wanted to work had to get permission from their husbands to keep their jobs. Banks simply made women resign once they tied the knot, and certainly after they had children.

That wasn’t the worst of it. Did you know it wasn’t until the 1960s that women in America gained the right to open a bank account? It actually wasn’t until 1974 that the Equal Credit Opportunity Act passed in the US. In simple terms, that means that, before 1974, single women—including those who were divorced or widowed—had to bring a man with them to the bank to sign their credit applications, no matter how much money they made. If you were a single woman, you couldn’t get a credit card in your own name.

In my novel, Alix St. Pierre might be the Director of Publicity at the House of Christian Dior, but she can’t get a loan. If she gets married, she has to beg her husband for the right to continue working. If she has children, and if they are girls, will she have to remind them that their dreams are limited in this world?

After serving her country during the war and putting her life on the line, it’s a disquieting future to contemplate. But so many women were made to not just contemplate that future, but to live through it. I salute them all.

__________________________________

The Three Lives of Alix St. Pierre by Natasha Lester is available from Forever, an imprint of Grand Central Publishing, a division of Hachette Book Group.

Natasha Lester

Natasha Lester is the New York Times bestselling author of The Mademoiselle Alliance, The Paris Seamstress, The Paris Orphan, and The Paris Secret, and a former marketing executive for L’Oréal. Her novels have won several awards, been international bestsellers and are translated into twenty-one different languages and published all around the world. When she’s not writing, she loves collecting vintage fashion, practicing the art of fashion illustration, and traveling the world. Lester lives with her husband and three children in Perth, Western Australia.