“We are Here.” On Rediscovering Safety and Beauty in the Wonders of Nature

Aimee Nezhukumatathil Considers the South Philippine Dwarf Kingfisher

From myths and the crackle-candy of fairy tales, I was taught to fear night. Once, a rain shower shimmered between slats on a roof during the darkest hour and soaked a woman’s nightclothes. Two months later, she found out she had a peach growing inside her and was locked in a trunk, dumped into the Aegean Sea.

Another time, a woman walks by a pond at twilight and hears a heavy shuffling behind her, so she turns around and the largest swan she’s ever seen looks her in the eye and down at her breast and back into her eyes again. No blinking. And then the swan lunges forward and nips at her collarbone.

I want to talk about how it feels to be brown and free in the woods, to not look over your shoulder anymore. To be able to open your hand to a gift. To not listen for footsteps or for someone other than these mucky beauties: Salamander. Squirrel. Mud puddle squelching under your toes. A titmouse jumping from limb to limb. I want to talk about not needing to run anymore, about learning to saunter, even dawdle, in the green.

Forgive me if I wanted to return safely. Safety was never given to me.

The brightest color I remember from that first month of the pandemic was violet. Specifically, the violet feathers of the South Philippine dwarf kingfisher. It had evaded scientists for 130 years, but an eye surgeon named Miguel David De Leon was the first person to capture it on film. After ten years of searching, one flew within his sight and, to his surprise, didn’t immediately fly away. From beak to tail, the bird is just over four inches, or slightly bigger than a crayon. And you’d need a whole box of them to describe it: Lilac. Lemon-belly. Fuchsia. Rose. Coral with bright blue-violet spots. The most electrically charged array of colors I’d seen in a month of so much darkness and worry and fear.

When I write poetry, I’ve missed making nocturnes—those observant songs of night—from a real forest, not one from the movies. In Japanese, forest is shinrin. Bath is yoku. Forest-bathing is shinrin-yoku. Names are important. What happened to my heart, the blood sloshing through me and behind my wide eyes, when I was not able to practice shinrin-yoku for years? What quiet violence was that to take away the green light, the pale moonglow, from my brown skin? And from so many other bodies, too?

Once, when I was pregnant with my first child, I was at a retreat in the woods and got lost trying to find my way back to my cabin at night. Thank goodness a pal was driving back to her cottage, saw me stumbling through the dark, and gave me a lift. I had promised my husband I wouldn’t be out late at night, that I’d be careful, but I’d lost track of time and needed the library. Determined not to get lost the next day, I gathered up light-colored stones in the bucketfold of my skirt like Gretel, and placed them into the shape of an arrow along the trail to the artists’ cottages. So by headlamp or by moon-spell, when I saw the arrow glow and point, I knew to turn left toward my temporary nest.

The other residents laughed when they saw it, I know. (I heard.) But they probably hadn’t had their wrists held by two unfamiliar men behind the campus tennis courts the summer after college. Never had their arms scratched open from being pinned against a chain-link fence. Never had to scream with every bit of might from every alveolus and bronchiole, only to have it all wasted in the sweaty center of a man’s strange palm.

I know the men who laugh long after the women stop. They laughed at girls with names like mine when they were boys. They still do. I’m just a chuckle to them. And I remember every one of those laughs.

Some called me Gretel for the next couple of days: Gretel, where’s your bike? Gretel, did you save any bread today? So be it. Forgive me if I wanted to return safely. Safety was never given to me. My safety outdoors as a brown girl was never a given.

There are so many birds on this planet found only in the forest. So what happens when forests are cut down to make room for another high-rise or resort? We know the answer. But most of us don’t want to think about it. What if the South Philippine dwarf kingfisher’s colorful plumage was a way of giving us a semaphore, a caution flag, to say, Haven’t you hurt enough? Can you let us keep our homes for once? Its beak and legs are orange. Its back shimmers the deepest violet, with indigo and coral spots. Its beak looks almost as long as the kingfisher is tall. The proportions can’t help but crack me up. You wouldn’t think such a small bird would be able to snatch a whole skink and gobble it down, but don’t underestimate these little ones—their beaks are formidable in their slicing and dicing.

Thank you, trees. I want to say thank you, thank you, trees—this time to the trees in Mississippi and Kansas for giving me shelter. And now, thank you, to the trees in New Hampshire, for letting me walk under you again at an artist’s residency in 2019. For the first time in years, I am glad to be alone in the woods.

Some men are like wind—you only notice them when they’ve done too much or too little—but perhaps one will have the impulse to notice red clover, mockingbird wing, or the small toad at the edge of the pond, instead of leering when a woman carrying a notebook walks past. Someone else can wait for them. Not me. This slow end of summer, I ride a bike and wear a headlamp past midnight on the trails. I haven’t been able to do that since I was twenty-one.

Open your mouth and taste the air. Let your mouth be agog, even, and especially, at night.

The trees give us back ourselves, our tiny cells, the animals and the crocodiles in us. Our fourth crocodile tooth glinting back at everyone who tried to harm us. We are here. We have gifts to give back. To trees who have sheltered trees who have borne witness to all the hurts doled out to brown people. To people with names that jumble and tumble on a tongue. Thank you trees in Mindanao, for providing a home to this bright kingfisher.

South Philippine dwarf kingfishers stay, build, and hunt only in tropical forests, where you can almost feel the water collect behind your knee or in the valleys of your neck. They bop and flit from branch to branch in search of their favorite slippery meal: not fish, but the emerald and coral-bellied skinks that love to hide and sneak in second-growth forests. Habitat loss is this kingfisher’s biggest threat.

My name is important. I have been mocked for it all my life. I’ll never change it now. I wish more people would care to get tree names right. Teach yourself the difference between red maple and sweet gum. Spicebush and sassafras.

Trees have allowed some bodies to dance this way, that way. They lift their hips, they prance in the forest, unbothered. Some seem to steady themselves. Maybe the floor that they were given is full of pine needles. On one of my nighttime residency walks, I spotted a pair of eyes studying me under the harvest moon. They shone at almost the same level of my own. I fumbled for my weak flashlight. I saw the body, a bright white tail. A tall dog? No—a deer—and two more, behind her.

One hundred and thirty years of avoiding humans trying to capture one in hand or by camera. The last time a South Philippine dwarf kingfisher posed long enough for a sketch, the president of the United States was Benjamin Harrison and Queen Lili‘uokalani still reigned in Hawaii. And the one that sat still for De Leon had such a sly look on his face, like he was posing on purpose: Fine, if you need a little boost of brightness during this global pandemic, take the picture—but hurry up! Hurry up before I change my mind!

Come sit with me under this water oak. This sugarberry tree. This molave tree. This rainbow eucalyptus. Before I change my mind. Open your mouth and taste the air. Let your mouth be agog, even, and especially, at night. Agape. Agape—which, someone once told me, is the Greek word for the highest, purest form of love.

__________________________________

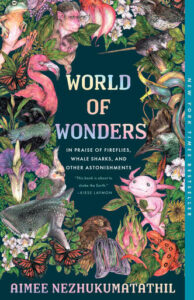

From World of Wonders: In Praise of Fireflies, Whale Sharks, and Other Astonishments by Aimee Nezhukumatathil. Copyright © 2024. Available now in paperback from Milkweed Editions. Featured image: Shantanu Kuveskar used by permission of Creative Commons CC by 4.0

Aimee Nezhukumatathil

Aimee Nezhukumatathil is the author of World of Wonders, an illustrated essay collection published by Milkweed Editions in September 2020, as well as of four books of poetry, including, most recently, Oceanic, winner of the Mississippi Institute of Arts and Letters Award. Other awards for her writing include fellowships and grants from the Guggenheim Foundation, National Endowment for the Arts, Mississippi Arts Council, and MacDowell. Her writing appears in Poetry, the New York Times Magazine, ESPN, and Tin House. She serves as poetry faculty for the Writing Workshops in Greece and is professor of English and Creative Writing in the University of Mississippi’s MFA program.