We Are All Witches: Elizabeth Willis and Nancy Bowen on the Contemporary Echoes of Centuries-Old Fears

E. Tracy Grinnell Talks to the Poet-Artist Team Behind Spectral Evidence

This longest night of the year is an important time for Witches and Pagans. It is a time for introspection and setting intentions for the new year. Settle in and relax with Spectral Evidence: The Witch Book to savor through the night. (All images courtesy the authors.)

*

E. Tracy Grinnell: One of the things that intrigued me when I received The Witch Book manuscript was that it began as two separate projects, each of you individually excavating your personal lineages and then bringing them into conversation with each other. Could you talk a bit about your projects before they came together?

Nancy Bowen: I grew up knowing that one of my ancestors was the Salem witch judge Samuel Sewall. As a feminist and witch-adjacent young person, I found this relation quite appalling. However, several years ago something compelled me to research him, and I found a much more complex situation that inspired me to create an installation that told his story.

Five years after the trials, Sewall publicly recanted and confessed his sins in church. He spent the rest of his life atoning for those sins. He wrote the first abolitionist tract that was published in the Massachusetts Colonies—“The Selling of Joseph”—in 1700. And he acknowledged the rights of women in his 1725 essay “Talitha Cumi.” He supported several young Nipmuc and/or Wampanoag men in his home and then paid for them to attend Harvard. Only one name is known—Benjamin Larnell. Sewall also left land and money in Point Judith, Rhode Island to Harvard College for the purpose of educating young English and Native men. Of course, these gestures were limited by the context of the colonial experience—“education” meant assimilating everyone to Christianity—but I was inspired by his attempts to make amends.

I created an installation in which Sewall faced off the twenty people he condemned to death. He was depicted as a large, abstracted figure wearing a hair shirt and weighed down with twenty small wooden gallows. The twenty dead were represented by abstracted gravestones with wings and skull heads and feet.

I called the installation “Spectral Evidence,” which was the phrase given to evidence based on dreams and visions, the “witchy evidence” that Samuel Sewall later believed was not in fact legally valid. I was working on this project during the Trump presidency. There were so many echoes with contemporary events—fake news and blustering men—that the project felt very current despite the fact that it was based in colonial American history.

There were so many echoes with contemporary events—fake news and blustering men—that the project felt very current.

Elizabeth Willis: My path was similar. When I moved to Massachusetts in 2002, an aunt asked me to visit the cemetery in Andover and told me we were related to at least a couple of convicted witches. If I’m remembering correctly, they were Martha Carrier, who was accused of causing a smallpox epidemic, and Mary Bradbury, who was accused of making a local sea captain’s butter turn rancid.

The logic of those convictions made me wonder what was going on beneath the surface. Martha Carrier was seven months pregnant when she got married, so she was not exactly the poster child for Puritanism, and she inherited her family’s property when her parents and most of her siblings died of smallpox, which made her the focus of a land dispute, so there were people who stood to gain by her conviction. Apparently, Cotton Mather considered her case an exemplary justification for spectral evidence.

ETG: Nancy mentioned beginning work on “Spectral Evidence” during the Trump presidency—was this about the time you began working on your poem “The Witch”?

EW: I wrote the poem around 2010, but before that I was doing research related to the Hollywood blacklist and the House Un-American Activities Committee, which similarly hinged on hearsay, accusations, and the naming of names. It drove Arthur Miller’s writing of The Crucible in the early ‘50s—and Ronald Reagan played an insidious early role in it when he was the head of the Screen Actors Guild.

The committee was deployed as a machine of disenfranchisement—withdrawing or threatening to withdraw individual rights in response to real or imagined acts of political or social will—especially targeting labor organizers, social justice workers, artists, writers, and other cultural workers but also gay citizens, particularly those working in government. Paul Robeson was not only blacklisted but had his passport confiscated so he couldn’t work abroad.

I wanted to know more about that boundary at which someone’s status changed from one kind of exemplary American to another. The committee and the people driving it clearly understood the power of performative language to shore up infrastructures of control, suspicion, and enmity, actively consolidating their own power while purporting to uphold a national identity of free speech and inclusivity.

That’s what I was researching back when the Supreme Court made their ruling on the 2000 presidential election, and in the years that followed when the surveillance and security industries were pouring unprecedented wealth into the pockets of people like Dick Cheney.

ETG: So, for both of you, recent histories and contemporary events intersected in fundamental ways with your personal investigations. What drew you to bring the two projects together, to present them in/as collaboration?

NB: During the time I was working on “Spectral Evidence,” my friends Susan Bee and Charles Bernstein introduced me to the work of Elizabeth Willis and in particular her poem “The Witch.” I loved the phrasing and the imagery it evoked, and I asked her if I could illustrate the stanzas. Her poem also felt very relevant to the political and cultural situation we were then in. And now with the overturning of Roe v. Wade, her poem feels even more pressing to me.

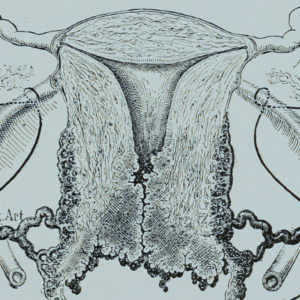

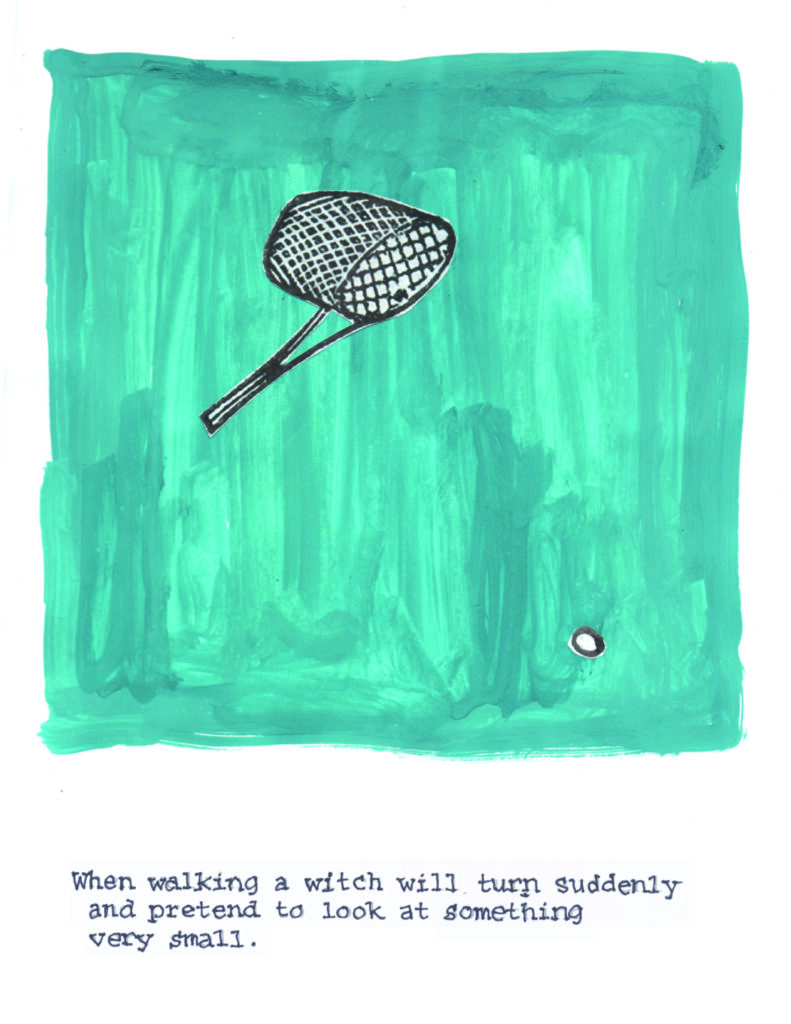

I talked to her about the poem and how she developed it. She told me about her research on the history of witches and how she watched old films like Haxan, a Danish film from 1922. Some of the lines in her poem were from her research and some she invented. I wanted to echo the idea of found language with found images, mixing those with other images I drew myself, and some that I found and altered. I like to construct images like a sculptor. I did not want to illustrate the lines directly or to use traditional stereotypical witch imagery like hats and brooms but to add a little friction to the experience.

So I tried to find an image whose visual meaning was slightly askew from the meaning of the words. For instance, I found an image that I liked of a hand emptying a glass, and it reminded me of the line about “dying of thirst” so I used it there. It was important also that this poem does not seem located in a particular visual time but makes references to several time periods. I chose some images that were from a 17th-century swimming manual and others from contemporary fashion.

EW: When I heard your story, I was fascinated by it—and by the work you were doing around it. When you told me about Samuel Sewall—not only looking at his actions and their repercussions when he was a judge but tracking the transformation that came from his own self-examination—I was struck by his commitment to a reparative path. His struggle of conscience cost him something, and this complicates the narrative in ways that pull it out of the binaries of good and evil.

I was also struck by the fact that the war against women’s autonomy was—especially early on in works like the Malleus Maleficarum (1494)—conducted through images. Engravings that show female pleasure in the absence of males were combined with scenes of cruelty, so you get strategically placed broomsticks, bodies that are part animal, and babies being sacrificed on the side. It was a genre specifically designed to associate female autonomy with the demonic and to fuel male anger while giving it safe haven under the guise of Christian devotion.

So, your decision to respond to that history through image-making seemed especially on point. About your question, Tracy, when I saw Nancy’s installation in Salem, with sculptures in the center of the room and the images with my text on the surrounding walls, I thought it had the feel of an exploded book, but the process of assembling it into an actual book with you and Rachael [Wilson] and Monti was where most of the collaborative decision-making came into play. To work collectively with you all seemed like a logical extension of the turn the work had taken.

So much of what we see playing out historically—including within present history—is the gaslighting of those whose experiences contradict the master narratives.

ETG: Returning to the book, now titled Spectral Evidence: The Witch Book, one of the things that is most powerful to me is that it does begin with the intimate work of personal excavation and reckoning, and imagination. In the global context of colonial history and capitalist exploitation of humans and nature, you begin with the individual, then engage in the relational (via collaboration) so that the conversation can open outward, become more inclusive.

I watched Häxan recently, and the scene that references an accused witch who was found sleeping naked prompted me to suggest the title of our conversation, “A Witch Sleeps Naked,” which is also the third stanza of Liz’s poem. I love thinking of personal reckoning and a willingness to make oneself vulnerable as “sleeping naked”…and beyond that, of course, is the absurdity of pathologizing whether or not one sleeps with clothes on!

NB: Some of the lines that I love in the poem “The Witch” are the ones that I see myself and all my female and femme friends in. “She appears to frown when she thinks she is smiling.” Well, haven’t we all done that? There is a kind of identification: Oh—I get it, we are ALL witches.

EW: I think there’s something very interesting going on in the movement between I, she, and we here. Part of the history we’re addressing has to do with keeping information held by women separate, so that if she/I/we feels at odds with the powers that be, if she/I/we is being told her sense of truth is categorical madness, then she/I/we are kept from establishing bonds with others who share similar senses of reality and desires for change.

So much of what we see playing out historically—including within present history—is the gaslighting of those whose experiences contradict the master narratives being told about the nature of reality and of individual experience. And it happens subtly and insidiously at the level of diction, with the most repressive political programs using the language of liberation to refer to its opposite.

*

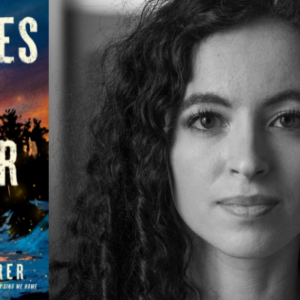

Nancy Bowen is a mixed media artist known for her eclectic mixtures of imagery and materials in both two and three dimensions. Bowen has shown widely in the United States and Europe, and she recently received an Anonymous Was a Woman award. She is currently a Professor of Sculpture at Purchase College, S.U.N.Y. She maintains a studio in the Brooklyn Navy Yard.

Elizabeth Willis’s most recent book Alive: New and Selected Poems (New York Review Books, 2015) was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize. Her other books of poetry include Address; Meteoric Flowers; Turneresque; The Human Abstract; and Second Law. She teaches at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop.

__________________________________

Spectral Evidence: The Witch Book by Elizabeth Willis and Nancy Bowen is available from Litmus Press.

E. Tracy Grinnell

E. Tracy Grinnell is the author of five books of poetry, including Hell Figures (Nightboat Books 2016). She is the Founding Editor and Director of Litmus Press.