We Are All Nobody: Mary Jo Salter on Finding Beauty and Community in Poetry

“Let’s try to put our own vanities aside when we write poems, and let’s read the poems by other people that make us feel most alive.”

“I’m Nobody! Who are you?” asked Emily Dickinson. It’s clear to many of us who she was and is—one of the greatest poets ever—and certain poems of hers suggest she knew it herself. Still, she had a sense of humor about swelled heads, and we love the zinger that concludes her eight-line Nobody poem:

How dreary—to be—Somebody!

How public—like a Frog—

To tell one’s name—the livelong June—

To an admiring Bog!

Readers delight in these lines because we recognize the empty pomposity that too often afflicts people (that is, other people). We also suspect that the hermetic Dickinson (who eschewed publication, dismissing it as “the Auction / Of the Mind of Man”) seems specifically to be skewering that subset of people called writers: the people who may have little to tell us other than their bylines, but who look to the admiring “bog” to confirm their brilliance. And among the general class of writers, which includes bestselling novelists and blockbuster screenwriters, we poets risk being the most deluded about our prospect of fame in that bog, now or ever.

The greatest poems may even, in exemplifying beauty, just marginally re-define it.

The business of poets, I would argue, includes at least some of these aspirations: to witness the world, including the layered, shifting moods of their own minds’ interiors; to feel deeply and also to think through their feelings; to experience life with all of the senses, which sometimes get profitably jumbled; to express some aspect of the human comedy and the human tragedy by exploiting the unique resources of a particular language or languages; to suggest with figures like simile or metaphor the surprising congruity of seemingly unlike things; to speak to their contemporaries about contemporary matters; to place themselves also within the history of humankind, including the history of literature, and to add something to it; to channel our universal musical instincts, our childlike but never merely childish love of song; to dare to remain uncertain and paradoxical and inconclusive as life itself, while also making a finished “thing,” a poem, of beauty. The greatest poems may even, in exemplifying beauty, just marginally re-define it, sometimes without the awareness of the reader.

*

I’ve been an editor and anthologist, loosely defined, a long time. In a “commonplace book,” although I didn’t know the term yet, I started copying out my favorite poems at age eleven. (My mother tended to put books of poems in front of me.) One of the first poems recorded in my little notebook, WB Yeats’s “After Long Silence,” concludes: “Bodily decrepitude is wisdom; young / We loved each other and were ignorant.” No chance that I knew what decrepitude meant; I must have liked the sound of it, and probably the oddness of that locution “young / We loved each other.” Poems usually win us first by means of sound, not meaning. Later I would understand that ending a poem on the word “ignorant” rather than the upbeat “we loved each other” was a very modern thing to do. In large, awkward cursive I also copied out “The Span of Life,” a poem of a single couplet, by Robert Frost:

The old dog barks backward without getting up.

I can remember when he was a pup.

Well, now I’m the old dog. Except that I like to think I will get up. I don’t want to nap my way through my last chapters of life: I want poetry, among other stimulants, to keep me fresh. If you’re reading this book, so do you. You may be a poet yourself. Or are you, dear reader, among the many who say that they don’t know much about poetry, but they know what they like?

Perfectly reasonable. I can’t say why a beautiful poem in your eyes is not a beautiful one in mine, or vice versa. Even after having taken on the daunting responsibility, with several much-revered coeditors, of selecting poems for three different editions (dated 1996, 2005, and 2018) of the 2,000-page, epoch-spanning Norton Anthology of Poetry, I still find it almost impossible to come up with Universally Useful Criteria for evaluating a poem. I was once chatting with colleagues on the Writing Seminars faculty at Johns Hopkins about our upcoming deadlines for posting the titles of new literature courses. We teased each other about the trendy titles and over-theorized reading lists we had come up with, and then one of us threw up his hands and said, “Why can’t I just call the course Stuff I Like?”

It was an amusing question, but not as naïve as it sounded. Literary anthologies, like literature courses, have always consisted, when you get right down to it, of nothing more or less than stuff that some mortal people liked. True, an editor of a large, comprehensive poetry anthology would be foolhardy and arrogant, if she happens not to like Shakespeare, to attempt erasing the fact of Shakespeare. Still, even Shakespeare started out as stuff liked by his local contemporaries—most of them not poets or playwrights themselves.

A knee-jerk pessimist eager to be course-corrected, I find myself this year cheered by the industrious hopefulness…of poets out there.

Even before embarking on editing this year’s Best American Poetry I had had the pleasure of reading most of the previous volumes; and I’ve had my taste broadened, time and again, by guest poet–editors of the past. In the final poem in this book, a former guest editor, Kevin Young, finds himself gazing at paintings in a museum and marvels at “what the world // couldn’t say till someone / saw it first”: that’s what I hope to discover in anthologies too.

The editors in this best-poetry series have always done the work of reading plenty of stuff they didn’t like in order to arrive at the stuff they liked, distinctive stuff that often sounded nothing like their own poems. A knee-jerk pessimist eager to be course-corrected, I find myself this year cheered by the industrious hopefulness, not to mention the stratospheric number, of poets out there. What emerged this year, as in all the Best American Poetry volumes, is the work of highly intelligent, feeling, talented people who deserve to be better known. Who merit our attention in this short, precious period we get to be alive.

*

One of the younger poets in this anthology, Stephen Kampa, may give me the right note to sign off with. His deliberately brief poem, “Someone Else’s Gift,” first published in a small but mighty journal, Literary Matters, seems in conversation with Shakespeare’s Sonnet 29, in which even the greatest of poets confesses to “Desiring this man’s art and that man’s scope.” Fretting over such comparisons, Kampa writes,

Means answering a roguish shout we follow

Down some smashed-bottle alley to a hollow

Recess, a doorway, where

If luck has tailed us on that lonely walk,

When we knock, because we have to knock,

No one will be there.

No one? Well, perhaps. As Dickinson wrote, “I’m Nobody! Who are you?” Kampa’s vision is a scary one, but beautiful because it has been expressed with such uplifting craft. Let’s make sure, then, that we ourselves are there when we knock. Let’s try to put our own vanities aside when we write poems, and let’s read the poems by other people that make us feel most alive. Let’s do it simply because we are human.

__________________________________

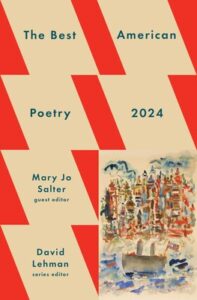

Excerpted from The Best American Poetry 2024 by David Lehman and Mary Jo Salter. Copyright © 2024 by David Lehman. Foreword copyright © 2024 by David Lehman. Introduction copyright © 2024 by Mary Jo Salter. Reprinted by permission of Scribner, a division of Simon & Schuster, LLC.

Mary Jo Salter

Mary Jo Salter is Professor Emerita in The Writing Seminars at Johns Hopkins University, where she taught from 2007 to 2022. She is the author of nine collections of poetry, all published by Knopf, including most recently The Surveyors and Zoom Rooms. Former poetry editor of The New Republic, coeditor of three editions of The Norton Anthology of Poetry (1996, 2005, and 2018), and editor of Amy Clampitt’s selected and collected poems, Salter is also an essayist, a lyricist, and a children’s book author. She lives in Baltimore.