We All Know Columbus Didn’t Discover America—So How Did He Become a Symbol of Its Founding?

Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz on the Erasure of This Continent’s Original Inhabitants

Mahmood Mamdani, in Neither Settler nor Native, locates the founding moment of the modern nation-state at 1492, noting it emerged out of two developments in Iberia. “One was ethnic cleansing, whereby the Castilian monarchy sought to create a homogeneous national homeland for Christian Spaniards by ejecting and converting those among them who were strangers to the nation—Moors and Jews. The other development was the taking of overseas colonies in the Americas by the same Castilian monarchy that spearheaded ethnic cleansing.” Mamdani emphasizes that modern colonialism didn’t suddenly start occurring in the 18th century but that European colonialism and the modern state were co-constituted.

*

A few months after Catholic entry into ethnically cleansed Granada, the Spanish monarchs contracted with a Genoese seaman who promised he could reach India by a shorter route by sailing west. Columbus landed not at already European “discovered” India but, rather, on an island of what is now called the Bahamas. The thriving Indigenous residents informed him that to the north and south and east and west stretched a huge landmass, two massive continents teeming with cities and tens of millions of acres of farmlands that would come to constitute the major portion of humanity’s food production. The rapacious crusade-hardened mercenaries representing Christendom were skeptical, until some voyages later they reached the continent at Central America, which they named Cabo Gracias a Díos (Thanks to God Cape). Two decades later a Spanish army would possess the heart of that landmass, destroying the most populated city in the world at the time, Tenochtitlán, in the valley of México.

October 12, 1492, is etched in the brains of many as the day of “discovery,” but the Indigenous peoples of the Western Hemisphere and of Africa and descendants of enslaved Africans regard the date as the symbol of infamy, domination, slavery, and genocide. Haitian historian Michel-Rolph Trouillot writes, “To call ‘discovery’ the first invasions of inhabited lands by Europeans is an exercise in Eurocentric power that already frames future narratives of the event so described Once discovered by Europeans, the Other finally enters the human world.”

The first formal celebration of Columbus in the United States came five years after the Constitution was ratified—the tricentenary of discovery on October 12, 1792. It was organized by the Tammany Society, also called the Columbian Order, that was founded in 1789 by a group of wealthy men in New York City. An obelisk dedicated to Columbus was erected in Baltimore in 1792, the first known public monument to Columbus in North America. Although Bolivarian revolutionaries named Gran Colombia after Columbus, the independent states founded from the former Spanish colonies did not take up celebrating Columbus until the 1920s, even then and now not as a formal holiday. In 1937, at the behest of the Knights of Columbus, President Franklin D. Roosevelt proclaimed Columbus Day an official federal holiday.

So, why did the United States, which at its founding had no direct geographical, calendar, or colonizing link to Columbus, embed the event and date as the very founding of the United States? Historian Claudia Bushman thinks the cult of Columbus rose in part because it eschewed the British source of US existence and located its origins to first founder of the Americas. At first, “Columbia,” meaning the land of Columbus, rather than “Columbus” was used for honoring Columbus. Columbia College, now University, was founded in 1754 as King’s College and was renamed Columbia College when it reopened in 1784 after independence. And the federal capital was named the District of Columbia. The 1798 hymn “Hail, Columbia” was the early national anthem and is now used whenever the vice president of the United States makes a public appearance. By 1777, a year after the settlers of the 13 British North American colonies declared independence, the poet Philip Freneau named what would become the United States of America “Columbia, America as sometimes so called from Columbus, the first discoverer.” There were others who advocated that the 13 states should adopt the name Columbia. South Carolina named its capital Columbia.

Brian Hardwerk observes, “Columbus also provided a convenient way to forget about America’s original inhabitants.” Bushman notes that “in early American textbooks from the 1700s Columbus is the first chapter. Columbus starts American history. There’s nothing about the Indians. Some of these books even show pictures of Columbus in colonial era clothing.” And, of course, Columbus was not even his name. David Vine asks, “Why do we call the man who some celebrate today as ‘Christopher Columbus’ when that wasn’t his name?” pointing out that his only known name historically is Spanish—Cristóbal Colón—not difficult to pronounce, but definitely not an English name. Because Colón was being repurposed to be the founder of the United States, his name was anglicized to Christopher Columbus.

Most significant, though, is that Columbus represented colonialism and imperialism that the original founders and future ruling classes fully embraced. In 1846, US senator from Missouri Thomas Hart Benton, who was basking in the glory of the US Senate’s declaration of war against México, explained to Congress that the war was a continuation of Columbus’s vision, “the grand idea of Columbus” who in “going west to Asia” provided the United States with its true course of empire, a predestined “American Road to India.” Benton also explained the racial impact of the arrival of the “White race” on the west coast, “opposite the eastern coast of Asia” would be a benefit claiming that the “White race” was unique in having received “divine command, to subdue and replenish the earth,” being the only “race” that searched for new and distant lands.

Columbus represented colonialism and imperialism that the original founders and future ruling classes fully embraced.

In 1861, a 20-by-30-foot mural was installed in the US Capitol building, titled Westward the Course of Empire Takes Its Way, symbolizing continental imperialism, which had come to be called manifest destiny. The US was mired in war with the secessionist Confederacy, but regarding imperialism, the two warring sides were in total agreement. The mural’s painter, Emanuel Gottlieb Leutze, was born in Germany in 1816, his family immigrating to the United States in 1825. His first work was titled Columbus Before the Council of Salamanca, followed by a companion piece titled Columbus in Chains. In a tribute to the European radical revolutions of 1848, which he supported, Leutze painted Washington Crossing the Delaware in hopes the revolutionists would be inspired by the US War of Independence establishing the white republic.

Mamdani’s argument that the nation-state was born in 1492 is validated by the conscious mythical founding of the United States as a white republic that like the establishment of the Spanish nation-state was founded on white supremacy and ethnic cleansing. Required courses in history were incorporated into US school curricula in the early 19th century introducing children and young people to Columbus practically as an ancestor. But clearly Columbus took on a renewed significance and purpose with the increasing presence of the Roman Catholic Church in the United States with the arrival of millions of Irish immigrants and the millions of Eastern and Southern European immigrants, many of them Catholic, particularly the four million Italians who arrived between 1890 and 1920. Trouillot writes that “ethnicity gave Columbus a lobby, a prerequisite to public success in US culture.” In 1866, there were fewer than 4,000 Italian Americans and only a few Spaniards in the United States, yet they already celebrated October 12th as Columbus Day in New York, and commemorations subsequently spread to Philadelphia, St. Louis, Boston, Cincinnati, New Orleans, and San Francisco. But the real boost for Columbus came from another source: Irish Americans and the Roman Catholic Church, with the 1882 establishment of the Knights of Columbus.

*

In the February 11, 1882, edition of Connecticut Catholic, an Irish American newspaper owned and edited by a Catholic layman, came the news, “Pursuant to a call issued by Rev. Fr. McGivney—over 60 young men assembled in the basement of St. Mary’s Church last Tuesday evening, February 7, 1882 and formed a cooperative benefit order to be known as the Knights of Columbus.” Father McGivney proposed Columbus as patron to the organization while James T. Mullen, who became the first “Supreme Knight” suggested the full name Knights of Columbus to better evoke the ritualist character of the order. Matthew C. O’Connor, the first “Supreme Physician,” asserted that Columbus was to signify that as Catholic descendants of Columbus, they “were entitled to all rights and privileges due to such a discovery by one of our fathers.” Although the Knights attracted Italian immigrants later in the century, the founding was largely an Irish American Catholic project.

Notre Dame historian Thomas Schlereth notes that the Irish American founders “apparently never entertained the idea of naming themselves after St. Brendan.” He explains that for the Catholics of New Haven it had to be Columbus, mainly because Columbus was already embraced as a symbol of the authentic US American and helped remove from them the stigma of nativism. It was a symbol providing, as they put it, “social legitimacy and patriotic loyalty.” As Catholic descendants of Columbus, they were entitled to “all the rights and privileges due such a discovery by one of our faith.” Father Michael McGivney was only 30 years old when he founded the Knights of Columbus and died eight years later. In October 2020, Pope Francis beatified McGivney, paving the way to sainthood, the highest tribute possible that the Roman Catholic Church could bestow upon the Knights of Columbus, illustrating the Vatican’s continued support for its 15th-century doctrine of discovery.

The real boost for Columbus came from another source: Irish Americans and the Roman Catholic Church.

By the time of the 400-year anniversary of their namesake in 1892, the Knights of Columbus were located in every state and soon would spread all over Canada, México, and the Philippines and become the largest body of Catholic laymen in the world with over two million members at the turn of the 21st century. Catholic historian Christopher J. Kauffman writes, “By adopting Columbus as their patron, this small group of New Haven Irish American Catholics displayed their pride in America’s Catholic heritage, evoking the aura of Catholicity and affirming the ‘discovery’ of America as a Catholic event.”

But it was also a patriotic event; Kauffman notes, “The society’s ceremonials led the initiates on a journey into council chambers where, with symbol, metaphor, and Catholic fellowship, they were taught the lessons of Columbianism: a strong attachment to the faith, a pride in American Catholic heritage,… and a duty to understand and defend the faith against its enemies, in short to display loyalty to Catholicism and to the flag.” In 1882, Thomas Cummings said to fellow members of the newly formed Knights of Columbus, “Under the inspiration of Him whose name we bear, and with the story of Columbus’ life as exemplified in our beautiful ritual, we have the broadest kind of basis for patriotism and true love of country.”

The organization spread rapidly in the Northeast with the backing of well-to-do Irish Americans and emphasized the shaping of “citizen culture.” Trouillot notes that “Columbus played a leading role in making citizens out of these immigrants. He provided them with a public example of Catholic devotion and civic virtue, and thus a powerful rejoinder to the cliché that allegiance to Rome preempted the Catholics’ attachment to the United States.” This was the beginning of the Americanization project at work.

__________________________________

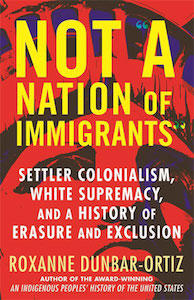

Excerpted from Not “A Nation of Immigrants”: Settler Colonialism, White Supremacy, and a History of Erasure and Exclusion by Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz (Beacon Press, 2021). Reprinted with permission from Beacon Press.

Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz

Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz grew up in rural Oklahoma in a tenant farming family. She has been active in the international Indigenous movement for more than four decades and is known for her lifelong commitment to national and international social justice issues. Dunbar-Ortiz is the winner of the 2017 Lannan Cultural Freedom Prize, and is the author or editor of many books, including An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States, a recipient of the 2015 American Book Award. She lives in San Francisco. Connect with her at reddirtsite.com or on Twitter @rdunbaro.