Ways of Remembering: A Father and Daughter Navigate Loss Together

“Is this my family’s thing? The need to pin memories down, preserve them in a drawer, put a frame around them?”

My father has untreated ADHD. Two years ago, at thirty-nine, I verified a longtime suspicion and was diagnosed with the same disorder. When we talk on the phone we talk at each other rather than to each other. Let me tell you something, my father says. Nancy makes the best meatballs. He tells me he fed some of the coveted leftover meatballs my stepmom made for him to a fox that frequents their yard. I think it’s sweet he shared them with a wild animal. I ran around the park today, I say. There were so many turtles on the log! By the time a sentence is out of either of our mouths, we’re on to the next topic, two frogs hopping around on lily pads, never diving below the surface.

For most of his life, his brother, my uncle Jim, was the person he frequently dialed and vice versa. I like to think of them as Irish twins, even though they were nineteen months apart. From the moment Uncle Jim was born, they became each other’s confidants. They’d talk about the guitars my uncle acquired for his impressive collection, or the latest Green Bay Packers game. They talked about the Studebaker their father had when they were kids, and the bands they used to be in or were in still, including Downhill Tangerine, an homage to some of their favorite classic rock bands from the sixties and seventies.

They talked about my uncle’s depression, too. They talked what seemed like a million times a day, jumping from subject to subject, two brothers with the kind of shared conscience that comes from a lifetime of loving each other, annoying each other, and healing each other. Until healing was no longer an option.

*

Starting in childhood, my dad and his three younger brothers possessed that elusive talent so many spend their lifetime seeking and never find. Family gatherings inevitably turned into jam sessions in my grandmother Mimo’s piano room, where she taught countless students over the years, and where I’d stretch out on a dark brown velvet couch and watch my uncles and father morph into younger versions of themselves, each strum of the guitar drawing them closer to simpler days when their main concern was which girl had a hold on their heart. Who cared about mortgages and medical ailments and any of the other obnoxious responsibilities of adulthood? When they started playing Beatles songs together, four men became boys again, reliving the decades that had shaped them.

*

As a kid, I’d love it when Uncle Jim would stop by to visit, because he’d almost always bring me a pack of Bubblicious watermelon or strawberry gum just so he could hear me say THAAAAAAAAAAANK YOU with the a drawn out for emphasis, thaaaank you! like he was giving me a new bicycle or a hundred books, thaaaaaank you! for this candy I will stuff into my mouth one piece after the other after the other because the gum loses flavor so quickly and I can’t stand it once it’s a bland wad of nothing, thaaaaaank you! for the sweetness, thank you for being kind. He loved the way I said thank you like he was giving me the moon instead of a short-lived treat. Why didn’t I chew gum at his funeral in honor of him?

Aren’t all fathers still boys at heart, capable of being charming and exasperating? And isn’t it easier to think of them this way?

Instead, I watched as my father held it together in front of one of the longest lines the funeral parlor had ever seen. If only he were here to see how many people loved him, I said to Mimo. Perhaps a living wake would have saved him from taking his own life. The overhead light kept flicking on and off, as if by some spectral presence, the result of an employee trying to urge people to keep it moving as they paid their respects for their longtime friend and guitar teacher, one after another offering their condolences as my family greeted them with a numbed astonishment. What a musician. What a good person. What a tragedy.

Because my brain works in overdrive and I’m always thinking about the past, present, and all the possibilities for the future, the crowded room contained more than the living bodies in it. I pictured my dad and my uncle as ravenous and impish boys, eating oily slices of pizza the owner gave them for free despite knowing they were the pranksters who called an hour before and placed an order under a fake name. I saw them as twenty-somethings sweating under the stage lights as they played for a rapt audience. I imagined my dad dialing Uncle Jim’s number, a sequence as familiar as his favorite chords. And I knew that months from that awful day, he’d reach for his phone on autopilot, wanting to share something with his best friend, forgetting for a split second no one was there to pick up.

*

From the comfort of home, my father reaches out to his adult children with the same frequency as the days when Uncle Jim was on speed dial.

He sends me a note:

Are you at work?

Yes!

👍

It’s his favorite emoji. I send him a NYT article about Trump being found guilty on all counts.

👍

I tell him to have fun on his trip to London.

👍

I ask him how he is.

👍

I send him a photo of my husband next to an old pickup truck that reminds me of the 1953 Dodge B4B he bought in honor of his brother. Made in the same month and year Jim was born, it’s one of his most prized possessions. Once again,

👍

He sends me links to articles about shark attacks in Florida and Cape Cod, even though I have no plans to go near the ocean anytime soon. Be careful!!!

He texts me photos of his (half-eaten) meals: hot dogs from a food cart in our hometown loaded with all the fixings, corned beef hash doused in ketchup, fried clams. (I’m allergic to shellfish, but looks good?)

Drive-by phone calls and texts are the main way he shows he cares, and they’ve increased in the six years since Uncle Jim passed away. Dad alternates between calling me and my sisters, my older sister who lives in Montana and my younger sister who until recently I shared an apartment with in Brooklyn. He has a knack for dialing at the most inconvenient times: when I’m on the subway platform as a train comes screeching to a stop or I’m sitting on the toilet or in a Zoom meeting. If I don’t answer, sometimes he tries me a few times in a row, a signal to most people that there’s an emergency. But most times, it’s not urgent. What’d you have for dinner? A quick FaceTime chat as he scrolls through social media or watches television. The equivalent of a thumbs-up. Okay, I have to go. Nance made meatballs.

How awful that we can’t hold on to everything forever—the homes and objects and moments and loved ones that disappear as quickly as those glimmering lights in the sky.

He’s also a master of snail mail. Sometimes he sends me photos he printed from my Facebook page, including a picture from a recent trip where I’m standing in front of the house we used to stay in on Nantucket when my parents were still together. I thought you’d want a framed copy.

He ships me (well boxed in plenty of packing material) a personalized pink sweatshirt with the phrase It’s a Filgate Thing (You Wouldn’t Understand). I store it in my dresser with the rest of my pajamas.

Once he sent me an article about UFOs, and I remembered the muggy summer night he picked me up from a community theater rehearsal in suburban Connecticut. What is that? he asked abruptly as he pulled over to the side of the road. We jumped out of the car, and I followed his gaze as he pointed out the lights above us moving impossibly fast in the night sky. We watched them wink out, leaving nothing but stars and a void.

*

When my parents first separated, my father, never much of a cook, would heat up cans of Chef Boyardee Beefaroni on the stove or buy me Big Mac value meals from McDonald’s on the weekends I’d stay with him. Some mornings we’d drive along country roads more populated by horses and American flags than humans to get to our favorite market, where my mouth would water as I waited for a bacon, egg, and cheese sandwich on a poppy seed roll. I’d slide the latest Archie or Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles onto the counter as my father took his wallet out to pay the cashier, and he’d buy the comic book for me without protest. Food and magazines and books were his way of showing love. It’s why when I had mono while I was an undergrad and could barely keep my eyes open, my father shipped a heavy care package of canned soups to the apartment I lived in in New Hampshire. Too weak to stand, I crawled to the front door and dragged the box inside, knowing it would get me through the worst of the illness.

*

My father loves some of his possessions almost as much as his kids. He’s attached to objects that serve as portals to the past. In his home office, he has constructed a shrine to his eternal youth: toy cars from the 1950s parked on glass shelves and cast in a soft warm light, a framed ticket and poster from the Beatles Shea Stadium concert he went to with Uncle Jim, a replica of the boat from Jaws my siblings and I bought him for his birthday: even ceramic figures of the Martians from Sesame Street. Surrounded by memorabilia celebrating juvenile joy, my father cocoons himself in a certain kind of suspended stasis, one that allows him to be five and twelve and sometimes seventy-three. Aren’t all fathers still boys at heart, capable of being charming and exasperating? And isn’t it easier to think of them this way, as boys equally delighted and distracted by their latest or fixed obsessions?

*

A few months ago, while sorting through drawers in my own home office and deciding what to keep and what to toss before I moved, I found a note my dad had tucked in my duffel bag the only summer I went to sleepaway camp, warning me to watch out for the bugs I so dreaded, and urging me to have fun.

I reread a card Uncle Jim’s ex-girlfriend handed to me at his funeral. Inside, a scrap of paper with words I made up as a kid. Uncle Jim loved them so much, he immortalized them.

I found letters from Mimo written to me on the antique rolltop desk I’ve since inherited. Dad brought it to the city for me and carried it up the steep flight of stairs to my apartment, while sweating and swearing.

Beloved Mish—where has the time gone, Mimo wrote on floral stationery. Seems like it was only yesterday that we went on our famous walks that produced some of your great stories.

I think of my sweatshirt, emblazoned on the front with It’s a Filgate Thing. Is this my family’s thing? The need to pin memories down, preserve them in a drawer, put a frame around them?

*

As someone with ADHD, pinning anything down is difficult. Moments come and go as quickly as my father’s phone calls. I want so many things: another pack of gum from Uncle Jim, another drive with my father to a market that no longer exists, to be back in Mimo’s living room, the sliding doors opening onto a deck overlooking snow-laced trees and Lake Windwing, my father and uncles talking over each other and communicating through a shared history of music. My grandmother bouncing her leg in time with “I Want to Hold Your Hand,” her low-heeled shoe, which matched her fuchsia blouse, dangling off her foot. When she died four months after Uncle Jim, I took that dazzling shirt and stored it in a sealed envelope, hoping to preserve her particular smell of lavender lotion and lake water. I haven’t dared open it since. I’d rather live in a world where my grandmother’s fragrance could still exist.

My father texts me a photo of Mimo’s house. It’s no longer owned by our family, and the front yard is overgrown, so green it hurts to look at. I feel a flash of possessiveness. How awful, I respond. How awful that we can’t hold on to everything forever— the homes and objects and moments and loved ones that disappear as quickly as those glimmering lights in the sky. But we can try.

__________________________________

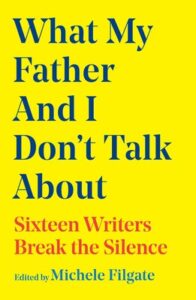

“Thumbs-up” by Michele Filgate appears in What My Father and I Don’t Talk About: Sixteen Writers Break the Silence, edited by Michele Filgate. Copyright © 2025. Available from Simon & Schuster.

Michele Filgate

Michele Filgate is the editor of What My Mother and I Don’t Talk About and What My Father and I Don’t Talk About. Her writing has appeared in Longreads, Poets & Writers, The Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, The Boston Globe, The Paris Review Daily, Tin House, Gulf Coast, Oprah Daily, and many other publications. She received her MFA in Fiction from NYU, where she was the recipient of the Stein Fellowship. She teaches at The New School.