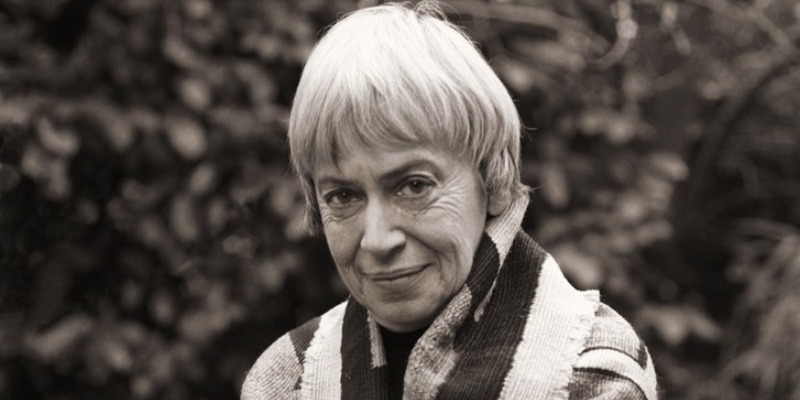

WATCH: Ursula K. Le Guin on Writing Fantasy as a Young Girl

“I was free in a way that I think it’s always been rare for a child to be free.”

The Journey That Matters is a series of six short videos from Arwen Curry, director and producer of Worlds of Ursula K. Le Guin, a Hugo Award-nominated 2018 feature documentary about the iconic author.

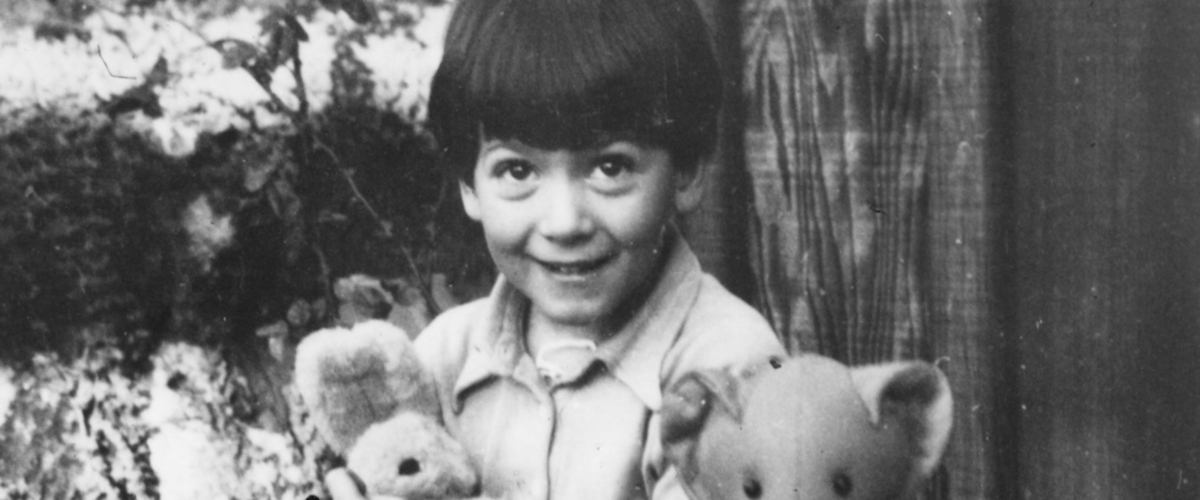

In the first of the series, Ebony Elizabeth Thomas introduces “Elves, Dragons, and Countries That Didn’t Exist,” in which Ursula reflects on how her childhood influenced her development as a writer.

The literary genius Ursula K. Le Guin is not only one of the esteemed foremothers of the current speculative renaissance in publishing and Hollywood, she is also one of the most brilliant and captivating authors of the past century in any genre. One of my favorite aspects of Le Guin’s stories is that her treatment of race and racial differences stands sentinel over most of her white contemporaries, attesting to the prescience, power, and enduring significance of her work. Together with fellow Hugo and Nebula award winner Octavia E. Butler, she redefined the boundaries of her genre, sparking a transformation in speculative fiction that points to our current era of narrative representation, challenging who deserves to be seen, heard, and represented in the fantastic, and ultimately giving birth to our wide-ranging landscape of contemporary speculative fiction.

In Le Guin’s stories, children and childhood often take center stage. In this video, we learn how her own childhood shaped the writer she became. I find many resonances across time and amid our differences: being an avid reader in a home filled with books and storytelling, cultivating a love for folklore, sharing playtimes and stories with siblings, casting stuffed animals and toys as characters in our first forays into fairylands. The role that her own childhood played in her writer’s journey surely is part and parcel of the resonances that her stories have for readers from all kinds of backgrounds. Her deep concern about children is evident, as well as her respect for their freedom and autonomy, including in one of her most well-known short stories, “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas.”

Claudia Rankine has famously termed the ways in which writers imagine race as the “racial imaginary,” noting that race is one of the primary ways that history lives within us all. None of us are exempt, and this imaginary is formed from earliest childhood. In “Omelas,” Le Guin provides one of the most important speculative metaphors for the racial imaginary here in the United States. The setting of a perfect city during a summer day recalls the belief of the Pilgrims that America would be a city set on a shining hill. As is the case with all utopias, Omelas hides a secret that is revealed to all residents once they come of age: their happiness is predicated on the misery of a single suffering child.

Although Le Guin notes that the story is meant to evoke scapegoating and was inspired by William James’s “The Moral Philosopher and the Moral Life,” it is easy to recall the ways that the prosperity of the US is due to “stolen people on stolen land”—that is, the suffering that Native and Black people faced through genocide, enslavement, and continued oppression. Without the suffering child, there would be no Omelas; without the suffering of Native and Black Americans, there would be no United States. This now classic story is so compelling and enduring that a recent episode of Star Trek: Strange New Worlds used it for its plot. While I am not certain that Le Guin was aware of this broader impact, the haunting story of Omelas still continues to generate fresh conversation and new narratives today.

It’s important to note that the heart and soul of “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas” is a child. In The Dark Fantastic, I wrote about how much I longed to see myself in the fantastic worlds that I loved so much when I was growing up. Le Guin’s approach to race was often subtle and sometimes imperfect by present standards, but as a reader, I found her methods of inclusion to be quite matter of fact: of course all kinds of people belong in all storyworlds.

In her Earthsea series, beginning with A Wizard of Earthsea, she depicted a fantasy world inhabited by a diverse cast of characters. The primary protagonist, Ged, is a young wizard of darker skin. One reading of Earthsea is that his journey serves as a metaphor for those of us who have been marginalized. He confronts prejudice and discrimination from those who fear his magical abilities and wrestles with his own inner demons. As a Black reader, Ged’s struggles drew me right into the series. Le Guin’s portrayal of the Archipelago as racially and culturally diverse challenges the conventions of traditional fantasy literature, where medieval European settings have been the norm until recently. It’s because readers and cinemagoers have been so carefully taught what a wizard looks like that Earthsea adaptations have faced controversy. In the 2004 adaptation, Ged was cast as white, a fact that displeased Le Guin. (As an avid fantasy fan, writer, and professor, it has been frustrating that nearly 20 years later, there has not been a more recent effort to bring Earthsea back to the screen.)

In short, Ursula K. Le Guin’s impact on speculative fiction, particularly in relation to childhood and race, remains profound and enduring. Le Guin’s ability to navigate the intricacies of race and racial differences sets her apart from her contemporaries, showcasing her foresight and the enduring relevance of her work. And through her stories, Le Guin demonstrates the pivotal role that childhood plays in shaping the fantastic realms she crafted, drawing upon her own upbringing to resonate across diverse experiences. As we reflect on Le Guin’s remarkable contributions through this video series, her legacy continues to foster discussion, inspire conversation, and propel new narratives, reinforcing the lasting impact of this luminary of fantasy, science fiction, arts, and letters.

—Ebony Elizabeth Thomas, author of The Dark Fantastic

*

Further reading:

Ursula K. Le Guin: Who Cares About the Great American Novel?

“Only in this view of the writer as a fully privileged male, a warrior, literature as a tournament, greatness as the defeat of others, can the idea of “the” great American novel exist.”

On Coming to Ursula K. Le Guin in My Own Time

“Her passing hit me harder than I expected, considering my slender acquaintance with her work, but that was the thing about Le Guin: to have lost her was to have lost a world I longed to visit.”

My Year of Reading Every Ursula K. Le Guin Novel

“Each of these books challenged me to reimagine what human culture might look like—challenged me to imagine how we might throw off the death grip of capitalism, and its attendant values of patriarchy and racism.”

Arwen Curry

Arwen Curry worked with Ursula K. Le Guin for ten years to create Worlds of Ursula K. Le Guin. As an associate producer, her projects include EAMES: The Architect and the Painter (2011), American Jerusalem: Jews and the Making of San Francisco (2013), Regarding Susan Sontag (2014), and five 30-minute science and technology documentaries made for the PBS member station KQED between 2012 and 2014. She also directed a short documentary, Stuffed (2008). Arwen is a former chief editor of the seminal punk magazine Maximum Rocknroll and has written for print, radio, and film.