The Journey That Matters is a series of six short videos from Arwen Curry, the director and producer of Worlds of Ursula K. Le Guin, a Hugo Award-nominated 2018 feature documentary about the iconic author.

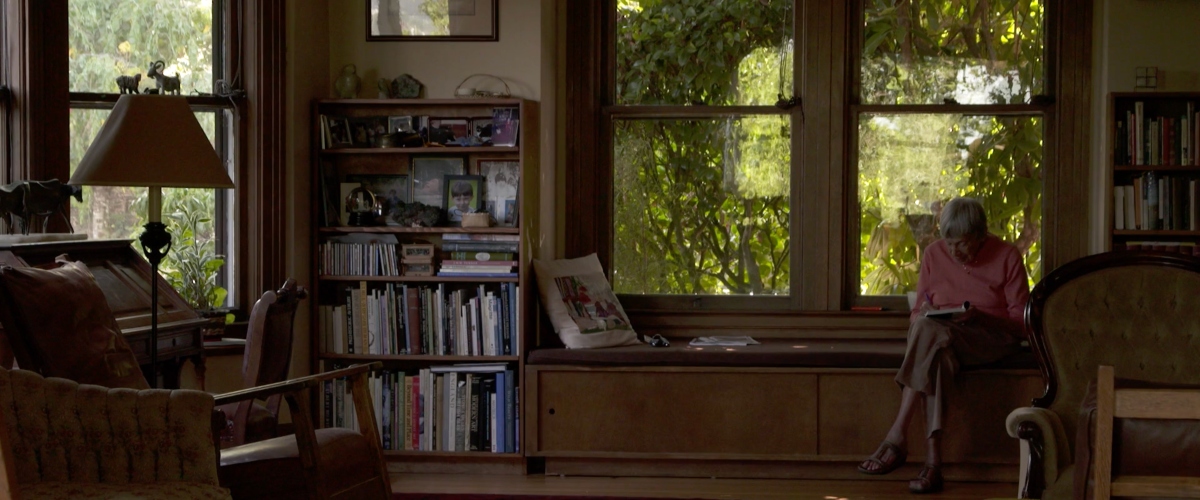

In the fifth of the series, Theo Downes-Le Guin introduces “Where I Write,” an intimate peek into Ursula’s study and her writing process.

Recently I viewed an online video titled “I Tried Ursula K. Le Guin’s Writing Schedule,” one of many such links. The production was snappy and well-intentioned, but the writer-presenter lost me when she described preparation of a “fancy breakfast.” The fried egg, tomato, and rocket sandwich bore no resemblance to mornings in my childhood home. Note to content creators: if you geek out on someone’s routine, do your research. Ursula wrote an entire essay about how to properly soft-boil an egg. That’s what she ate for breakfast. Not fancy.

Questions about process and routine are unavoidable for writers. While it seems churlish to withhold answers, I suspect many writers don’t enjoy these questions. Ursula certainly didn’t. She felt that too much focus on process was distracting for aspiring writers, and that her answers might sustain the distraction. Eating the same breakfast or using the same pen as Ursula K. Le Guin will not help you write like Ursula K. Le Guin. But the frequency and fervency with which such details are pursued indicates that many believe otherwise. In any case, one shouldn’t want to write like Ursula K. Le Guin. One should want to write like oneself, which means developing one’s own routine and process.

If you nevertheless feel compelled to learn about Ursula K. Le Guin’s Writing Schedule, bear in mind that the quoted schedule, from a 1988 interview, was her ideal, not her reality. Her actual schedule changed throughout her life, in response to circumstance. She was consistent in her preference to write in the morning, when she felt most in touch with her unconscious, and most vigorous. Accommodating this preference was often difficult. For years, she forwent morning writing to get my sisters and me dressed, fed, and cared for. Even when I (the youngest) was old enough to be kissed out the door to school, she couldn’t settle down till the better part of the morning had passed.

Writing when you prefer to write is a privilege; most writers don’t have the privilege all the time, and many never have it. In the inevitable conflict between ideal and actual, loving to write helps a lot. Ursula didn’t often complain about process or schedule, that I recall, in part because she so looked forward to writing. She craved the physical act, the creative flow, the time alone with her intellect. Writing at imperfect times or with a lousy pen was infinitely preferable to not writing at all. In this regard, she was lucky. A writer who dreads writing may still produce magnificent results, but what a tough life that must be.

A deviation from Ursula’s flexibility on when and how to write might be where she wrote. I admire writers who can write anywhere—in a coffee shop or on a long flight—but I don’t understand it, because that’s not the model I grew up with. Had we Starbucks in the 1960s, I am comfortable asserting that Ursula would never, ever have written in one. If circumstance had dictated that Starbucks was the only place she could write, the world would be impoverished of her art. She could write at a desk in a crowded apartment, in a hotel room, on a ship, or at a residency; she could write in a city, by the sea, forest, desert, or river. She could not write in a public place with strangers talking and working and drinking.

As a young author, the location of Ursula’s desk changed with each apartment or rental house. In the Portland, Oregon, home in which she settled for nearly 60 years, she found a room of her own. At first, the tiny corner room that eventually became her study was occupied by me, in a crib. I feel a bit guilty about that, as the study is a magical snuggery whereas the attic to which she initially was consigned was always cold or hot and the built-in desk very rickety. But Ursula was, at that time and by her own description, a housewife. The corner study was adjacent to the main bedroom, and she felt it more important to sleep near her baby than to have a perfect writing room.

When Ursula assumed her rightful perch in the corner study, after the publication of A Wizard of Earthsea, she replaced the crib with a cot for napping. Writing and sleeping were often adjacent in her life, as dreaming and the unconscious are close to the surface in her books. Napping may seem at odds with her comments about the hard, physical and emotional labor that novel-writing demands, and her skepticism about writer’s block or waiting for muses. Nevertheless—perhaps to deprogram the formidable work ethic she inherited—Ursula was as generous to herself with sleep as she could be. In the liminal space between asleep and awake, she found an imaginative resource that profoundly shaped her art. Perhaps that’s a lesson from Ursula K. Le Guin’s Writing Schedule from which we could all benefit.

—Theo Downes-Le Guin

*

Further reading:

Why I Decided to Update the Language in Ursula K. Le Guin’s Children’s Books

“My job is to bring my mother’s work to new generations of readers, not to revise it.”

Ursula K. Le Guin: Dictators are Always Afraid of Poets

“Take the rules seriously and somehow or other, as you follow them, you find that the necessity of having to do something gives you something to do.”

A Writing Lesson from Ursula K. Le Guin

“The sound of the language is where it all begins.”