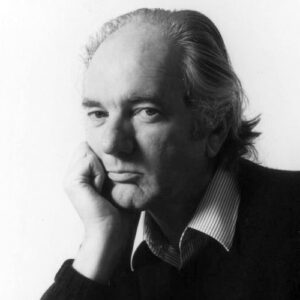

Watch Joan Didion Talk About Writing as Aggression

Happy 82nd Birthday, Joan!

Joan Didion, legendary journalist, essayist and novelist who has delighted, informed and inspired countless numbers of readers and writers (“A young female essayist saying they’re influenced by Joan Didion is like a young female singer-songwriter saying they’re influenced by Joni Mitchell,” Meghan Daum said once), turns 82 today. To celebrate her birthday, I dug up (read: Googled for) this footage from a 1970 interview she gave to Tom Brokaw, who introduces Didion by describing her as “this physically frail, reticent woman,” who “writes spellbinding prose in a style that is spare and occasionally sinister.”

“It’s the only aggressive act I have,” Didion says of her writing. “It’s the only way I can be aggressive.”

Actually watching Didion say this, so cool and small behind her large sunglasses, is a complex feeling for me—she does look supremely unaggressive, her voice is thin and almost dainty, she seems to be shrinking slightly from the interview. Brokaw even seems to notice, asking her if she’s more comfortable in front of the typewriter than she is “here—not just on a television interview, but in almost any other situation.” Yes, she says, but explains that actually, she’s most comfortable “performing”—be that writing or cooking. When she sits at a typewriter, she says, things change: she is “totally in control—of this tiny, tiny world.”

It’s hard not to read this in a gendered way—the use of writing to allow her into a traditionally masculine manner of behavior, the mention of the kitchen as her other primary realm of comfort, the allusion to a lack of control away from the typewriter. But I actually don’t think Didion’s writing is the only aggressive act she has. First of all, journalism itself is aggressive—I mean the physical, pre-writing action of it: you go out, you ask questions, you drag stories out of people, you expose them—and Didion is an excellent journalist. There’s something aggressive too in her persona (and maybe her personality), in, as Lili Anolik put it in Vanity Fair, her “cool-bitch chic.” That kind of coldness is something that female essayists aren’t often allowed, even now—or at least not as often as their male counterparts. I wonder what Didion would have to say about the ongoing discussion of (women writing) likeable vs. unlikeable characters. And as a woman who has been, at times, considered overly aggressive both on the page and off (my apologies to the ankles of people who played soccer against me in the early 2000s), I wonder, if Didion had been born 40 years later, would anything be different?

This interview is not, of course, the only time Didion has characterized the act of writing as belligerent. In her 1976 essay “Why I Write,” she explains:

In many ways writing is the act of saying I, of imposing oneself upon other people, of saying listen to me, see it my way, change your mind. It’s an aggressive, even a hostile act. You can disguise its qualifiers and tentative subjunctives, with ellipses and evasions —with the whole manner of intimating rather than claiming, of alluding rather than stating—but there’s no getting around the fact that setting words on paper is the tactic of a secret bully, an invasion, an imposition of the writer’s sensibility on the reader’s most private space.

When asked about this idea in a 1978 Paris Review interview, Didion said (and I imagine her shrugging), “I am always writing to myself. So very possibly I’m committing an aggressive and hostile act toward myself.” This seems true to me—after all, a reader who feels invaded by a writer’s prose can just close the book and go have a sandwich. For the writer, very often there is no escape.

At the end of the interview, Brokaw asks Didion if she feels optimistic about the future.

“The future of what,” Didion says, sly.

“The future of Us,” Brokaw clarifies.

“I don’t know,” she says. “I hope so.”

More than 30 years later, I hope so too. Happy birthday, Joan.

Emily Temple

Emily Temple is the managing editor at Lit Hub. Her first novel, The Lightness, was published by William Morrow/HarperCollins in June 2020. You can buy it here.