“Was It I Who Came Back Home?” On the Return of Catherine Dior and Other Survivors of Ravensbrück

Justine Picardie on a Homecoming Freighted with Suffering

When Catherine Dior vanished into Germany in August 1944, her family endured the agony of not knowing where she was, or whether she would ever return. And as reports about the devastating conditions in concentration camps began to surface in the early months of 1945, Herve des Charbonneries was forced to contemplate the possibility that she had not survived. His son Hubert told a Dior archivist, “We thought she would never come back. My father was in Paris during the Liberation, and then returned to Cannes. We still had no news of Catherine… The family heard nothing from her for nine months.”

Christian, meanwhile, continued to work as a designer in Paris for Lucien Lelong. When he reflected on this period in his memoir, he wrote: “I sometimes wonder how I managed to carry on at all … for my sister, with whom I had shared the cares and joys of the garden at Callian, had been arrested and then deported… I exhausted myself in vain in trying to trace her. Work—exigent, all-absorbing work—was the only drug which enabled me to forget her…”

And yet Christian did not forget Catherine; nor did he give up on her, but instead came to rely on a clairvoyant in Paris named Mme Delahaye, who told him that his sister would return. Indeed, in the opening pages of his memoir, Catherine and clairvoyance are linked, when Christian acknowledges the “good luck” that was such an important feature of his life “and the fortune tellers who have predicted it,” placing particular emphasis on the clairvoyant who “obstinately predicted” Catherine’s safe homecoming, “even at the worst moments of our despair.”

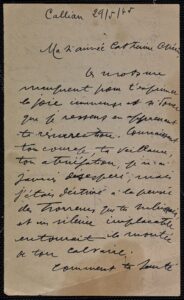

Lettre de Maurice Dior à Catherine Dior. Collection Christian Dior Parfums, Paris.

Lettre de Maurice Dior à Catherine Dior. Collection Christian Dior Parfums, Paris.

But the first real information about Catherine did not emerge until the middle of April 1945, thanks to a well-connected acquaintance named Alix Auboyneau, whose brother-in-law led the Free French naval forces, and whose husband was appointed as a diplomat by General de Gaulle. On 19 April, Christian sent a letter to his father, from his Rue Royale apartment. Maurice Dior was seventy-three years old and still living in the farmhouse in Callian, cared for by Catherine’s former governess, the faithful Marthe Lefebvre. “Mon petit papa,” wrote Christian, “you must be strong. How much longer must we wait until we see our darling [Catherine] again?” He goes on to explain that Alix had driven by car to Weimar, in central Germany, in search of Catherine and other friends of hers: “She arrived the day after the liberation of the camp.” The timing and location suggests that the camp in question was Buchenwald, which was six miles to the north-west of Weimar, and liberated by US forces on 11 April. At this point Catherine was still being held eighty miles to the east, in the Buchenwald sub-camp of Markkleeberg.

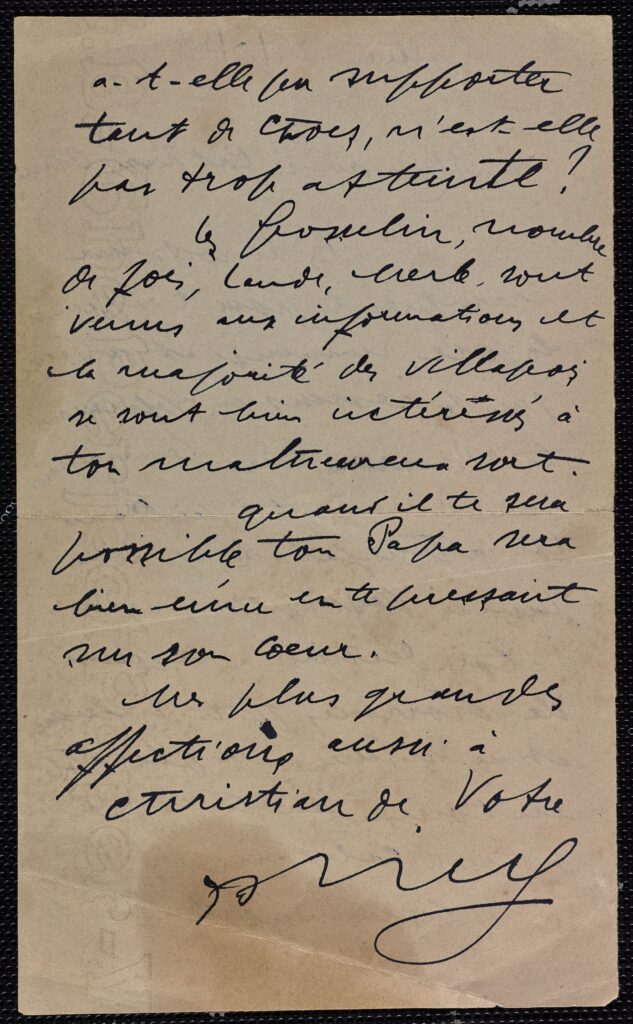

Lettre de Maurice Dior à Catherine Dior. Collection Christian Dior Parfums, Paris.

Lettre de Maurice Dior à Catherine Dior. Collection Christian Dior Parfums, Paris.

Christian’s letter continues: “Of all the people that she was searching for, she could only find a trace of our darling [Catherine]. So we have—relatively—a chance. Two or three days before the liberation of the camp, the majority of the deportees, nearly all of the women, had been dispatched towards Czechoslovakia. Alix found Catherine’s name on a list that, by chance, remained at the camp in Weimar.

“The war is moving fast. Let us hope that her release will come before she gives up. I send my love to both of you, and despite our dashed hopes, we must have faith… “

On the same day that Christian wrote to his father, and Catherine was in the final stages of the death march, Janet Flanner composed her “Letter from Paris” for the New Yorker. In it, she reported the sorrow that the French felt at learning of President Roosevelt’s recent death, following a brain hemorrhage at the age of sixty-three. “The increasing malaise, now that Roosevelt must be absent from the peace, and the unexpected return last Saturday of thousands of French prisoners liberated from Germany, juxtaposed fear and happiness in a melange that Parisians will probably always remember in recalling that historic weekend…“

The first contingent of prisoners of war flew back in American transport planes: eight thousand men landed in Paris on 14 April. Flanner described them as looking thin and weary; but it was the appearance of three hundred women the next day that truly shocked her. They came from Ravensbrück (which had not yet been liberated, but the Swedish Red Cross had succeeded in negotiating their early release in exchange for Germans held in France). Their stricken faces and broken bodies were the visceral proof of the atrocities they had endured. “They arrived at the Gare de Lyon at eleven in the morning and were met by a nearly speechless crowd ready with welcoming bouquets of lilacs and other spring flowers, and by General de Gaulle, who wept… There was a general, anguished babble of search, of finding or not finding. There was almost no joy; the emotion penetrated beyond that, to something nearer pain. Too much suffering lay behind this homecoming… “

Of this group of three hundred women, eleven had died on the journey back to France. One of the survivors, wrote Flanner, “six years ago renowned in Paris for her elegance, had become a bent, dazed, shabby old woman. When her smartly attired brother, who met her, said, like an automaton, ‘Where is your luggage?,’ she silently handed him what looked like a dirty black sweater fastened with safety pins around whatever small belongings were rolled inside. In a way, all the women looked alike: their faces were gray-green, with reddish-brown circles around their eyes, which seemed to see but not to take in. They were dressed like scarecrows, in what had been given them at camp, clothes taken from the dead of all nationalities. As the lilacs fell from inert hands, the flowers made a purple carpet on the platform and the perfume of the trampled flowers mixed with the stench of illness and dirt.”

“There was almost no joy; the emotion penetrated beyond that, to something nearer pain. Too much suffering lay behind this homecoming.”

In the following weeks, more women returned from Germany, all of them bearing physical scars and psychological wounds. Catherine Dior was among those who arrived in Paris at the end of May 1945; her brother Christian met her at the train station, but such was her emaciation that he did not recognize her at first. He took her back to his apartment at Rue Royale, where he had lovingly prepared a celebratory dinner for her, but she was too sick to eat it.

On 29 May, their father and Marthe Lefebvre both wrote to Catherine from Callian, rejoicing at her safe return. The two letters survive in the Dior archives as memorable testaments to the power of faith and unwavering love. Marthe declared that she had prayed to St Theresa every day to protect her beloved Catherine: “we have never prayed in vain. I look forward to the great day when I shall see you again, I kiss you with all my heart, how I love you. Please share this with dear Christian, who must be delighted.” Maurice Dior expressed himself with similarly devout emotion: “My much loved darling Catherine, words fail me in expressing the immense and tender joy that I feel upon hearing of your resurrection. Knowing your courage, your bravery and your abnegation, I have never despaired, but I was distraught at the thought of the horrors you were suffering, and the implacable silence that surrounded your path of the Cross.”

Rereading Maurice Dior’s letter to his daughter, as I have done many times, it seems to express the profound difficulties faced by families who were overjoyed by the return of their loved ones from Germany, yet could never fully comprehend the indescribable truth of the death camps. The challenge of giving voice to unspeakable experiences is also evident in Janet Flanner’s second report for the New Yorker, dated 27 April, describing her encounter with one of the French survivors of Ravensbrück, a twenty-five-year-old resistant to whom she gave the pseudonym Colette. “Her sorrowing blue eyes looked like the eyes of someone who has almost died… Her mind seemed quiet and clear. Her only trouble was loss of memory, which embarrassed her; she had suffered intermittent amnesia because she had been starved. She had lived through constant and humiliating horrors, some of which ‘on ne peut pas nommer.’”

Although there were nameless things too terrible to recount, Colette did speak to Flanner about the prisoners who had not yet been liberated from the camp, and those who would never return: “Thousands of women dwelt and died at Ravensbrück, in terror, confusion, pain, and despair… Neither she nor any of the other women could forget what they had learned by heart and in body. On their minds, and in their memories, were the thirty thousand other women still in Ravensbrück.”

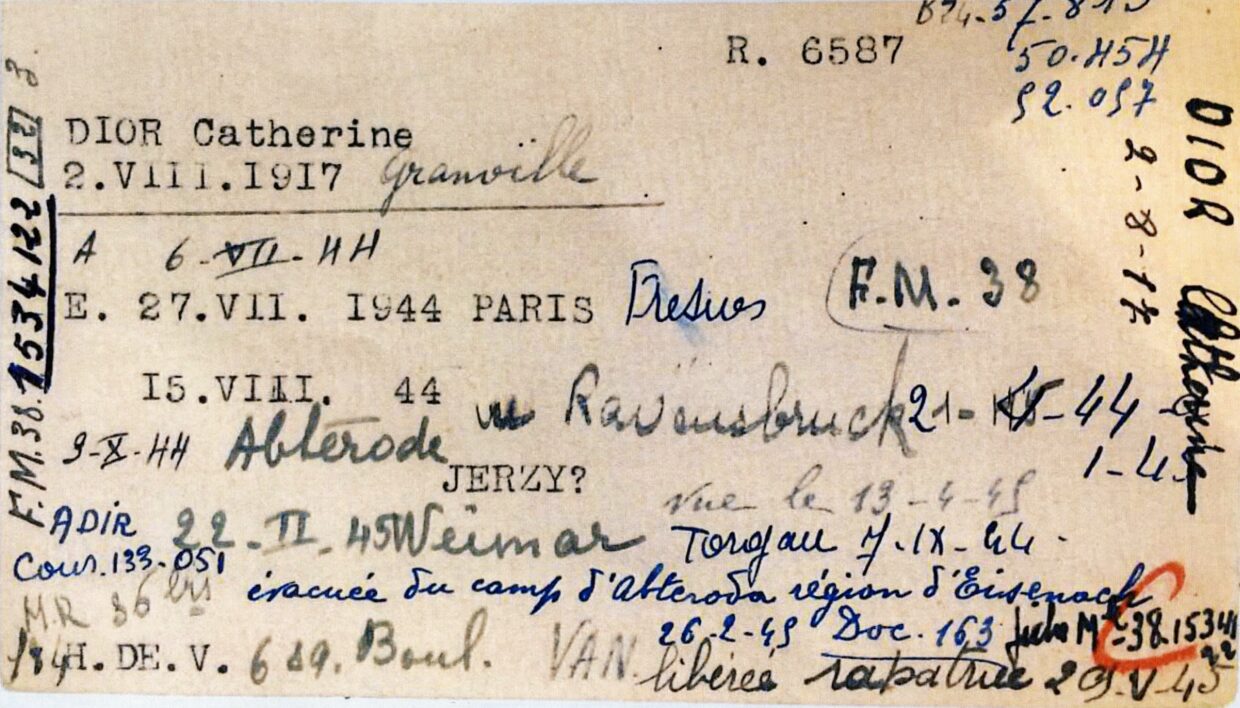

CATHERINE DIOR Carte de déporté RECTO. Collection Christian Dior Parfums, Paris.

CATHERINE DIOR Carte de déporté RECTO. Collection Christian Dior Parfums, Paris.

Denise Dufournier, who was in the first group of three hundred French women to be freed from Ravensbrück, subsequently described her memory of the experience in an interview that appears in Anton Gill’s book, The Journey Back from Hell. She was dressed in “a silk black evening dress, deeply decolletee,” that had been randomly allocated to her from the camp storeroom (a vast depository for the belongings of Holocaust victims) to wear on her journey home. “It didn’t strike me as anything other than a little odd at the time, but of course it was surreal. The surreal had become the normal for us—and maybe for the SS, too. None of us lived in the real world, but now it looked as if we might at last really be going back to it.”

Yet Denise’s long-awaited return to Paris did not, and perhaps never could, live up to her expectations: “leaving the train very quickly became a horrible, sad experience, because there were thousands of people there, and they were asking us for news of their loved ones, many of whom we didn’t know, but also there were many whom we knew to be dead.” Her brother was waiting at the station to meet her: “I was in a filthy temper. I think it was because I was so ill. My brother was certainly shocked when he saw me—he knew I’d been a prisoner, but he had no conception of how we’d been treated.”

Denise remembered that several relatives subsequently asked her “the most ridiculous questions, in ignorance,” although she acknowledged that it was difficult for them to even begin to imagine the terrors of a concentration camp. She was aware, too, that her homecoming was less traumatic than those of many others: “A friend discovered that the Nazis had shot her little sister in the street one day during the war. People returned to find that their whole families had died in air-raids; such discoveries, on top of what they’d been through, was too much to bear…”

Another of the French survivors, Micheline Maurel, wrote a powerful testimony about her return home to Toulon, and the vast gulf that she felt separated her from people who had not experienced the Nazi camps, nor witnessed the mass rapes by the Soviet troops. “The neighbours came from all over to meet the ‘deportee.’ I was the centre of attraction. Cousins came from afar to visit me. At first I was very excited, I greeted everyone, I answered all the questions. Then I became so exasperated that I shut myself in my room and refused to see anyone.”

The curiosity she encountered suggests that by this point, despite the taboo on discussing sexual violence, Micheline’s family was aware of the possibility that it might have occurred. “The questions I was asked were always the same: ‘Tell me, were you raped?’ (This was the one question that was most frequently asked… ) ‘Did you suffer much? Were you beaten? Were you tortured? What did they beat you with? Were you sterilised? And the Russians, were they so awful? Do you mean to tell me you had no other clothing?… And just how did you manage to survive’” Micheline eventually asked herself an even more searching question. “Officially, it is true, I did return. But in a real sense, was it I who came back home?” Her mother later observed that what had most disturbed her, more so than Micheline’s gauntness, was the “crazed look” in her eyes, while one of her brothers noticed that she appeared not to understand what people were saying.

For Micheline, as for so many other survivors, the camp could not be left behind in Germany, and the past still possessed her.

______________________________________________________

Excerpted from Miss Dior: A Story of Courage and Couture by Justine Picardie. Published by Farrar, Strauss and Giroux. Copyright © 2021 by Justine Picardie. All rights reserved.

Justine Picardie

Justine Picardie is the author of several books, including her critically acclaimed memoir, If the Spirit Moves You: Life and Love After Death, and the international bestseller, Coco Chanel: The Legend and the Life. She is a contributing editor to the UK edition of Harper’s Bazaar, having previously been its editor-in-chief. She was formerly an investigative journalist for the Sunday Times, a columnist for the Telegraph, editor of the Observer Magazine, and features director of Vogue. Miss Dior: A Story of Courage and Couture is her latest book.