“Warnings Imply You Have a Choice.” Rebecca Solnit in Conversation with Margaret Atwood

Celebrating 40 Years of Orion Magazine

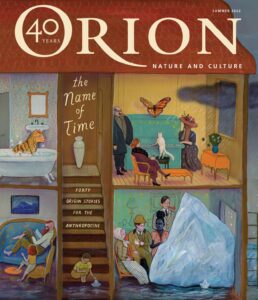

This year Orion magazine celebrates forty years of publishing environmental writing and art. To mark the occasion, the magazine inaugurated two lifetime achievement awards, including the Orion / Barry Lopez Award for Achievements in Letters and Environments. Named after Orion’s long-time collaborator, the late Barry Lopez, the award was presented to Margaret Atwood by Rebecca Solnit during the magazine’s fortieth anniversary gala.

The two writers were in conversation about the similarities between Atwood and Lopez’s work, how the history of writing about the Arctic influenced Atwood, how the legacy of Rachel Carson’s environmental writing continues to impact writing today, and how Atwood was never told that “girls don’t do that.” This is a transcript of their conversation.

*

Rebecca Solnit: It’s a joy and an honor to be talking to you because you’re the first recipient of the Orion / Barry Lopez Award for Achievements in Letters and Environments. It honors authors whose work reflects a complex and compassionate relationship with the natural world. It’s only eighteen months since Barry’s death. We’re here to congratulate you and to talk about your work and Barry’s work, and maybe the relationship between you two and the natural world. I know you and your partner Graeme [Gibson] met Barry some years ago, and I wonder what the circumstances were and what you remember about it.

Margaret Atwood: I remember it very clearly because [Graeme and I] got on a ferry from Vancouver and went up the Inside Passage. Then we went to the Alaska panhandle and met Barry when he was living there. And the first thing anybody said to us, it wasn’t Barry, but it was somebody with him, they said “welcome to Alaska, where the women are men and the men are animals.”

Solnit: Did you spend time with Barry?

Atwood: Yes, we did. We were there for some literary festival that he was involved with and he and Graeme became correspondents. Graeme put Barry into the Bedside Book of Birds.

Solnit: I wonder what you think about Barry’s work in relationship to yours. In some ways I often think of Barry as kind of pointing us towards the good. He’s holding up encouragements, while you’re often holding up warnings.

Atwood: No, I think it’s two sides of the same coin. So if you’re someone pointing towards encouragement, there’s something they need to be encouraged about. And if you’re pointing to a warning, well, that’s a form of encouragement, too, because if you actually want the person to get eaten by the nine-headed Hydra, you don’t tell them it’s in the cave. You do not warn them. So warnings are a form of “don’t go there” and warnings imply you have a choice. I think warnings are pretty encouraging.

Barry Lopez and Margaret Atwood.

Barry Lopez and Margaret Atwood.

Solnit: You’ve never been called a nature writer, have you?

Atwood: No, I haven’t, which is surprising. But Barry was more than [a nature writer], too. Arctic Dreams really opened up possibilities for me as a young writer. I think it did for a lot of people. It was such a remarkable book and Barry was definitely in love with the north and those spaces. A few generations before [him], people had just begun to celebrate the desert, so his celebration of the north still felt rare then.

Arctic Dreams really opened up possibilities for me as a young writer. I think it did for a lot of people. It was such a remarkable book and Barry was definitely in love with the north and those spaces.

Solnit: How did you and Graeme perceive the book when it came out in 1986? I feel like there hadn’t been much appreciation of the Arctic at that point.

Atwood: There really hadn’t been, not in that decade. There had been some earlier works in the 19th century. But what came back were drawings that made [the Arctic] look like it was full of snowy white palaces with chandeliers of ice and pinnacles, really another world. That was an age when people didn’t travel a lot and there were no airplanes, so the Arctic was another universe and they found it very romantic and strange. That’s also about the time you get the Franklin expedition, which disappeared mysteriously, and a number of other expeditions and rescue stories, all very romantic. And there’s some lighter writing.

Canadians, oddly enough, weren’t very interested in [the Arctic] in the 19th century. It was the British who were crazy about it. It was very connected to them with whaling. They were sending these whale expeditions to places like Hudson Bay. Then you get the Scott expedition of Antarctica dying romantically. Little do people remember that six members of that expedition actually survived, which was considered bad form of them. [Laughs] They were all supposed to die romantically.

Solnit: One of the extraordinary things about having lived a long time is seeing the world change so much. I just reread the essay you wrote to for the new edition of Silent Spring, and part of what was so striking is how cogently you describe the transformation of consciousness around the environmental world. You wrote that one of the core lessons of [that book] was that things labeled “progress” weren’t necessarily good. Another was that the perceived split between man and nature isn’t real, and that the inside of your body is connected to the world around you. You also write that your body has its own psychology, that what goes into it, whether eaten or breathed or drunk or absorbed through your skin, has a profound impact on you. We’re so used to thinking this way now that it’s hard to imagine a time when general assumptions were different, but before Carson they were.

We’re so used to thinking this way now that it’s hard to imagine a time when general assumptions were different, but before Carson they were.

You have also lived through profound changes around gender and feminism and sexual orientation and race and understandings of the environmental world—through so many revolutions. I think those were things that Barry also was very aware of and that both of you really helped to bring about in different ways through your work.

Atwood: Rachel was an absolute heroine. She took a complete barrage of bad publicity thrown at her by chemical companies at the time. I have a personal connection to that story because I had two uncles in the Annapolis valley who were apple farmers. This was in the days before they knew how extremely carcinogenic these sprays were. And my mother can remember kids playing in the spray from the apple sprayers. They just thought it was fun. It’s like a mist. So, we’re not a cancer family. We’re a heart and stroke family. But both of those men got cancer earlier, and earlier than they should have. I’m sure [the sprays] had something to do with that.

My dad, of course, was very aware of Rachel Carson’s work, because before her, it was the accepted wisdom to spray forest infestations. He used to say—and this was true—that these sprays killed a lot of birds and other things, but didn’t kill the insects. They survive, they become resistant, and then they make more and more resistant insects. And they can reproduce a lot faster than we can. So we needed other ways of dealing with infestations, because the long-term effects of that were pretty bad.

Solnit: I wanted to wrap up with something from the wonderful review of your most recent book in The Guardian. It begins: “How do you evade a rampaging crocodile? By zigzagging as you run, according to Margaret Atwood, since crocodiles, apparently, struggle to navigate corners.” Have you been outrunning crocodiles all this time? And if so, what are their names?

Atwood: I never actually out ran one. But in the north of Australia, they have these big crocodiles called sea crocodiles. They’re very smart. We were told “don’t ever brush your teeth in the same place.”

Solnit: I was thinking of it in a more metaphysical way. As in, expectations about what you were allowed to do and who you were supposed to be and what writing could be.

Atwood: Well, I think all that just came from ignorance. I wasn’t aware of what I was supposed to be and what the expectations were, so I didn’t really feel burdened by them. I had a mother who was a tomboy and didn’t do any of that stuff that I hear from other people about what the older generation did to them. “Girls can’t do this. Girls don’t do that.” I just didn’t hear it. So I wasn’t that aware of it. As for writing, the landscape was so devoid of anybody who was visibly a writer when I was a teenager, that there just were no expectations. That’s lucky in a way. It means you make it up yourself.

Solnit: Lovely to talk to you, Margaret, and hope to speak soon in real life.

____________________________

Writer, historian, and activist Rebecca Solnit is the author of more than twenty books on feminism, western and indigenous history, popular power, social change and insurrection, wandering and walking, hope and disaster. She is also an advisor to Orion.

Margaret Atwood has published more than fifty works of fiction, essays, and poetry, in more than forty-five countries. She is the first recipient of the Orion / Barry Lopez Award for Achievements in Letters and Environments.

Founded in 1982, Orion is a quarterly, nonprofit magazine that publishes fiction, nonfiction, poetry, and art about the environment. You can subscribe by clicking here or by gifting a subscription to someone who cares about the planet as much as you do.