Wallace Shawn: How Should a Person Be?

On Revenge, Punishment, Bravery, and Cowardice

Most of those who have dreamed of a more just world, who have perhaps spent their lives trying to prepare for one, have confronted the cold intransigence of the world’s entrenched elites, the dug-in repositories of luck and strength, and they’ve come to the conclusion that these ruthlessly greedy and heartless people will never give up power if blood is not spilled, that only violence can possibly dislodge them. And yet those who triumph in violent combat are by definition triumphant; they’re by definition victors, and they’re by definition powerful, and, whatever else they are, at that moment of victory they’re strong, and they’re lucky. At least at that moment, they’ve become the lucky elite.

And this brings us naturally to the questions of revenge and punishment. Because if the unlucky were ever indeed to remove the lucky from their current position of supremacy, the issue of “what to do about the lucky” would immediately be on the table, and the questions of revenge and punishment would immediately arise.

We all, naturally, dream of revenge. It’s one of the most enjoyable and thrilling of fantasies. We all become excited when we imagine the day when those whom we’ve learned to despise, those whom we feel have gotten away with so much for so long, will finally pay a price, will finally receive the reward they’ve earned. And yet—the person who takes revenge, at that very moment, becomes too powerful; the person who punishes, at that very moment, becomes too powerful.

Revenge and punishment both imply, “Even if I’d been you, and I’d had your life, I would never have done what you did.” And that in turn implies, “I wouldn’t have done it, because I’m better than you.” But the person who says, “I’m better than you” is taking a serious step in a very dangerous direction. And the person who says, “Even if I’d had your life, I would never have done what you did” is very probably wrong.

There is a thing inside each of us that we experience as the will, the “I.” We’re all aware that there are warring impulses inside us, and sometimes we feel that our will is on one side and some powerful internal force is on the other side. Some people struggle not to drink alcohol. There’s an institute in Sweden that helps principled people who find themselves struggling with a sexual attraction to children. In privileged societies, many people struggle with themselves not to eat the extra rolls that remain sitting on the table when the dinner is over. We all go through various sorts of struggles, and sometimes the thing we experience as our “I” wins, and sometimes it loses. What we don’t know, though, and what science can’t tell us, is whether it was ever possible for that struggle to have had a different outcome from the one it had. In my opinion, and I can’t prove that I’m right, though I can’t be proved wrong, the answer is probably never yes.

If two people compete in a game of tennis, no one knows who will win before the game begins. But when the game is over, it’s often possible for a skilled observer to explain why the winner won. The outcome was ultimately determined by the way that the strengths and the weaknesses of the two players interacted in that particular game on that particular day in that particular place.

Struggles that take place inside a human being are harder to observe, but I’ve never seen any reason to doubt that the facts about a person’s current circumstances, in addition to the facts about their current personal makeup—their original genetic composition, changed and developed by the habits and beliefs and psychological characteristics they’ve acquired during their lives—determine the outcome of their inner struggles. The struggle inside the human being is very real, just as the tennis game is real. Before the tennis game begins, no one knows what factors will influence it. No one knows, for example, that a sudden noise will distract one of the players at a crucial moment. All the same, the sum of the factors—including the sudden noise—will determine the outcome of the game. And in a similar way, the balance of forces within the individual—including their reactions to the environment around them—will determine the outcome of their inner struggles. If an alcoholic tries not to drink and fails, it’s because their impulse to drink was too strong, or their will was too weak, or both were true, and in any case, their “I” “lost control” over their actions—that is, they did what their “I” truly didn’t want to do. Did they struggle as hard as they could? We can’t know whether they did or not. Did they create their own nature and determine how strong their will would be? No, they didn’t.

I can decide that I want to become a better person. I can try to become a better person, and maybe I’ll succeed. But I don’t have the ability to discard all the elements of myself that may make that task of becoming a better person difficult.

When danger suddenly appears in our lives, and we need to make a choice—allow the escaped slave, hunted Jew, or undocumented refugee to hide in our house or send them away—we might turn out to be courageous, or we might turn out to be cowardly. In that moment of crisis, a vast number of factors that are hidden from our own consciousness are set feverishly to work inside us.

Our fear of the price we might have to pay for a courageous choice is a factor, but so are the things our various friends and loved ones have said to us over the years, so are the books we may have read, so are the examples set by people we know and people we don’t know. In the first moment of crisis, we have no idea what we’re going to do. But to tell our friends today that if a crisis comes tomorrow, we know we’ll be courageous, is simply foolish. And to righteously denounce the person who ultimately made the cowardly choice is foolish also. “Morality” may—if we’re fortunate—tell us what the better choice is and help us to fight for it within ourselves. Morality can influence our behavior; perhaps in some cases it will determine our behavior. But the actual process of decision-making takes place in secrecy; it happens in a private room from which we’re escorted out at the last moment. And even if we know what the right choice is, and we long to make that choice, the balance of forces inside us may compel us to go in the opposite direction.

Bernard Madoff was an intelligent and successful New York business executive who swindled a great many people out of an extraordinary amount of money. Radovan Karadžić was a Bosnian Serb psychiatrist and politician who committed many war crimes during the 1990s Bosnian war, including ordering the deaths of 8,000 people who had gone to an area called Srebrenica that the United Nations had declared to be a safe zone. Did Madoff have the ability not to swindle his clients? Did Karadžić have the ability not to massacre the people in Srebrenica? And what about me? If I’d been in their circumstances, would I have done the things they did? Possibly not, if I were still me. But if I had had Madoff’s brain and Madoff’s life, I would have been Madoff, and I think I would have done what Madoff did, and if I’d had Karadžić’s brain and had had Karadžić’s life, I would have been Karadžić, and I think I would have done what Karadžić did. And consequently I can’t help feeling that the whole apparatus of blame, judging, hatred toward those who’ve done terrible things is fundamentally wrong and ought to be discarded, and that punishment and revenge are based on assumptions that are fundamentally false.

Punishment, of course, is one of the possible techniques a community can use (a time-honored one, obviously) to indicate or emphasize what sort of behavior it doesn’t like or doesn’t condone, and the fear of punishment can certainly influence people’s behavior. And in certain cases perhaps people find it actually enjoyable to exact revenge. All the same, punishment and revenge are both still unjust, because there’s absolutely no way to determine that the person being punished, or the person against whom revenge is taken, was capable of behaving differently from the way they behaved.

__________________________________

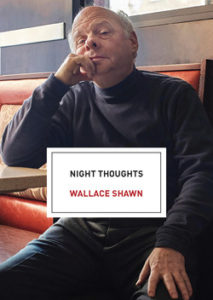

From Night Thoughts by Wallace Shawn. Used with permission of Haymarket Books. Copyright © 2017 by Wallace Shawn.

Listen: Wallace Shawn talks to Paul Holdengräber about his new book, Night Thoughts, the infinite appetites of Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin, taking yourself seriously, and what’s in store for civilization.

Wallace Shawn

Wallace Shawn is an Obie Award-winning playwright and a noted stage and screen actor (Star Trek, Gossip Girl, The Princess Bride, Toy Story). His plays The Designated Mourner and Marie and Bruce have recently been produced as films. He is co-author of the movie My Dinner with Andre and author of the plays The Fever, The Designated Mourner, Aunt Dan and Lemon, and Grasses of a Thousand Colours.