Visual Disposability: How Photographic Practice Dehumanizes Black Bodies

Kimberly Juanita Brown on the Long, Global Tradition of the Antiblack Gaze

Featured image: Cover page of the New York Times, September 21, 1994. Courtesy of PARS International.

Mortevivum is the term I have come up with to understand a particular photographic phenomenon: the hyperavailability of images in the media that traffic in tropes of impending black death. These tropes cohere around an ocular logic steeped in racial violence (and the nostalgia engendered therein), and they make any tragedy, any crisis, an opportunity for viewers to find pleasure in black peoples’ pain.

The easy accessibility of a range of visual imagery adhering to these tenets constitutes the repetition of a way of looking measured by their staying power. Since photography’s invention, black life has been presented as fraught, short, agonizingly filled with violence, and indifferent to intervention. Living death in a series of still frames, refusing complex humanity.

Mortevivum constructs the late modern advent of photography as uniquely positioned to make profligate the fungibility, to use Saidiya Hartman’s term, to continually frame the contours of black subjectivity. Photography’s ability to render blackness as stagnation (via loss, crime, famine, poverty, and death) is visually normalized and held in place by the power of the imagery and our collective inability to see beyond the limitations of our cultural bifurcations.

I am interested in how the viewer receives and processes images of the dying and the dead, particularly when those in the photographs are black. What I am calling a cartography of the ocular (moving from national location to national location, but always under the cover of blackness) has specific dimensions: a viable and recognizable enemy, the failure of other people’s sovereignty, and the global ability to reinforce white supremacist ideals.

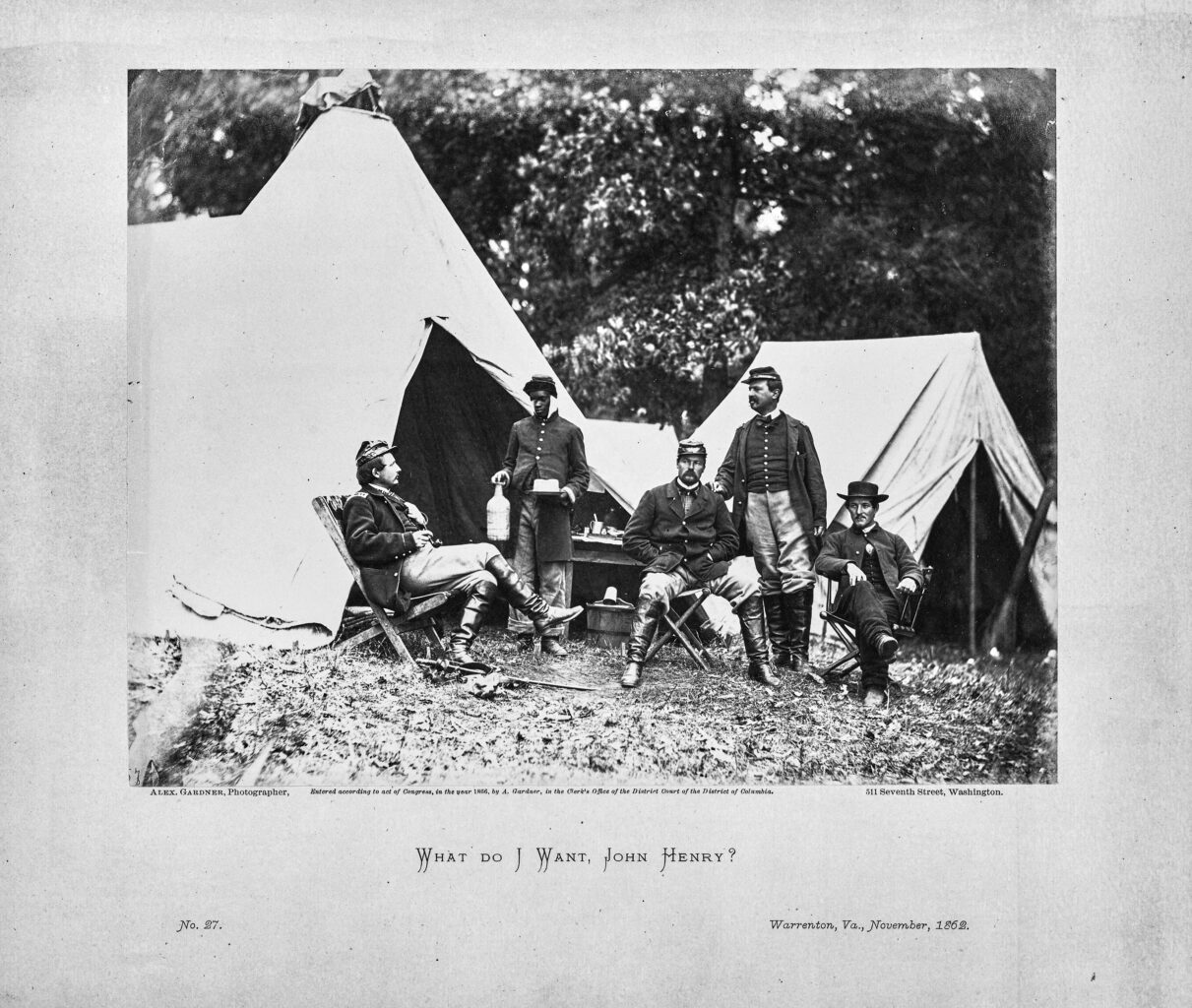

Alexander Gardner, What Do I Want, John Henry? Warrenton, Virginia, November 1862. Courtesy of Getty Images.

Alexander Gardner, What Do I Want, John Henry? Warrenton, Virginia, November 1862. Courtesy of Getty Images.

Cartographies of the ocular manage to span the reach of antiblackness in the global world. They tell us how blackness is treated as a forfeiture of worth, offering evidence of this forfeiture in an avalanche of graphic imagery. An examination of Pulitzer Prize-winning photographs from the last forty years is instructive. Violent imagery coalesces around black subjects from present-day Zimbabwe to Ethiopia, to California, New Jersey, and Liberia. If we were to draw out a map illustrating instances of antiblackness, it would cover the known world. This book is the way I make sense of the depth and breadth of imagistic othering rendered black.

For mortevivum is, in its very construction, a photographic production. Although it has tendrils of other properties of representation, the term as I am deploying it is about the force and the power of photography in the field of production over which so much has been inferred and assumed. Documentary photography, to be precise, for it is within the space of the document that an adherence to what is constructed as evidence and realism in this genre takes center stage. Black subjects are perceived and remanded to the space of photographic stasis that consumes and corrupts their ability to be autonomous outside of the violence of antiblackness.

Since photography’s invention, black life has been presented as fraught, short, agonizingly filled with violence, and indifferent to intervention.

What could be more insistently destructive than the swift mobility of print imagery in daily newspapers, digitized and received in various forms of immediate consumption? This project explores photography’s import and utility on the cusp of the twenty-first century—at the tail end of analog photography, the beginning of the photographic digitization of imagery and the burgeoning prowess of the World Wide Web. This is a project that looks back to anticipate the forward thrust of a post-September 11 permissive objectification, as after 2001, the dead become a swirling mix of Middle Eastern and South Asian subjects, rendered as deserving of a photographic death and a permanently suspended life.

*

This is how you read a photographic image: I was greeted with marked illustrations of antiblack violence when, after living in Orlando, Florida, for five years, I returned to the city of my birth, New York. I arrived in early June 1994. Moving from one bus/train station to another, I had to readjust to the common presence of newsstands that dotted the city. I would linger as I had previously in front of these ubiquitous kiosks, surveying a range of daily newspaper front covers, deciding which would be worthy of my fifty cents.

It took me months to work out why I was noticing something in repetitive patterns that I might have missed had I not spent some years away from the bustle of New York City. Each day as I maneuvered the streets in silence, I was met with jarring photographic renderings of black death. As I instinctively averted my eyes, I remember being unsettled, but I was unsure as to why.

I knew enough about the “if it bleeds, it leads” mantra of late twentieth-century journalism, but here was something else. It was devoid of living “human images” and instead trafficked in specific dead bodies—corpses for which there was no need for regard. It was then that it hit me: all the dead bodies shown on the front page of multiple newspapers were black. It was as if there was an implicit agreement that black subjects were fungible in ways others were not. Furthermore, everyone looking at these photographs understood this too.

Indeed, antiblackness so organized the visual disposability of black subjects that the final decade of the twentieth century is filled with examples, large and small, of this repeated expendability found in documentary photography. Of the repetition of images of dead black bodies in daily newspapers during the 1990s, Deborah E. McDowell writes, “These postmortems circulate specifically within a journalistic economy linked to the dissecting and quantifying obsessions of social science linked especially to its historically racialized obsessions with separating the ‘informative’ from the ‘deviant.’”

Blackness intertwined with “objective” data acquisition is an engorged abscess of racialization always on the verge of rupture. When it finally bursts, it renders the wound of white supremacy healed (falsely), and always at the expense of black people. These images have very little to do with the purported evidence of news dissemination. Their informative offerings are always spurious and always open to critique. McDowell continues: “And even if they are seen, these post-mortems do not invite protest.

Perhaps they do not strike readers as gruesome because the press has accustomed them to viewing the face of black death. Indeed, in contemporary public media and discourse, death is synonymous with blackness and constitutes the absolute limit of ‘difference.’” Blackness and death as “synonyms” is the tally here. How else to understand the century-long deployment of photographs against black humanity, the submersion of subjectivity alongside a rigid visual framework that constricts a fully embodied black presentation?

Photography has helped facilitate a subject/object fallacy wherein, under the guise of the evidentiary, black subjects are presented as objects of crises waiting for an external (white) articulation. Legibility here means being legible to viewers who traffic in the visual demise of those registering as black. The length and depth of this trafficking is a foreshadowing event that produces its own mechanism of engagement. To unpack and unfurl its significance, we must go back to move forward. If global antiblackness is the atmosphere, as Christina Sharpe reminds us, then photography clings invisibly to the skin like mist. This makes the ephemeral/stasis structure of mortevivum an unwieldy navigation.

Visual constituencies make the archive of unbelonging tenable and available. Where harm is done, they ask us to tread lightly while attending to all there is to see. Where value is assumed and expected, there is its constant reinforcement and a willingness to extend ocular grace. Where there is an understanding of collective disposability, dispossession is the navigation and the end point. The black subject’s quotidian existence is balanced between photographic dispossession and disregard, informed by a system that claims lives in the light and in the dark. So here we are, at a photographic demarcation point that now includes the continuing costs of white supremacy on black subjects globally.

__________________________________

Excerpted and adapted from Mortevivum: Photography and the Politics of the Visual by Kimberly Juanita Brown. Copyright © 2024. Available from MIT Press.

Kimberly Juanita Brown

Kimberly Juanita Brown is the inaugural director of the Institute for Black Intellectual and Cultural Life at Dartmouth College where she is also an Associate Professor of English and creative writing. She is the author of The Repeating Body: Slavery's Visual Resonance in the Contemporary.