LXXXIII (Chanterelles)

Black trumpets, whale-colored pamphlets, or shingles, or ears, bookmarks of the netherworld, breakfast food of the box turtle.

For a long time, she could not find them, hovering just above them the way an inanimate lamp will hang blindly above the lucidities of geometry.

And then she saw them risen in clusters on the mossy rocks, firm and articulate, as when first translated from the original rain.

Bat wing, toad mask, vole shield: they turned darkly in the alchemy of the skillet—in the mouth, they transmit a tenuous signal,

a hint of perfume, but musical—songs with morals, light things broadcast before the planetary news on the underground station.

LXXXIV

Sunday morning and Brown worries about the silence of his squirrels. While he chatted with friends on the porch last night, the young father or mother leapt onto a dead branch and fell with the branch a good twelve or fifteen feet. It merely shouted goddam and scurried home, and still no noise from their pine. They have not seemed churchgoers. A headstrong couple since the days of their madcap courtship, when they chased each other from roof to treetop, bickering and squalling like any cousins in love. Then, of course, they did what mating animals do after the ritual displays or the fights in discotheques. They built their nest. He follows them, though they are not even people. He hopes they are alive.

LXXXV

Mann regarded his man-selves. Drastically. Mann addled. Mann indigo. Mann challenged by man-hubris and man-baggage sang to the portal in the bathroom vanity. The dewlaps under his chins vanished. Mann the tiger endorsed his man-animus, his man-shadows. Elegiac Mann raised his brow to topmast. Mann down sang to Mann up. Mann out to Mann in. Mann quicksand to Mann aurora borealis. Mann the old man saw Mann the boy. In Jakarta, on the twentieth of May, whitening his teeth, dyeing his hair. Mann loved himself in spite of the age difference and the language barrier.

LXXXVI

Ticks have no virtues unless the hedge of irritation they sow on labia and scrotum be also moral hedge against pornography. Hard cases, addicts, intimate apocrypha, ticks mark the spot where creation got out of hand and God stopped. For they have made unto Luck a place where he stoops as in a perverse prayer and peers between his legs at the mirror image of his own backside. The tiny ones do not devour streptococcus. The large ones, rubies on the spines of bird dogs, will not excrete cures for lupus or impetigo. Still, he honors their night. Body scratching itself in sleep, conscious mind hovering like a kid with a remote control. So creeps the ancient hope that suffering embellishes the soul.

LXXXVII

Dogs of the world, anonymous wanderers, moral conundrums, they gather by the road, scavenging milk cartons thrown from the bus: feist pups galled with mange, old hounds, blind and lame, at the end of their utility. Such he once whispered secrets to and begged to keep and was commanded to lead into the woods to execute and bury. And his father was not a cruel man. And Saint-John Perse wrote, “I had a horse. Who was he?” Strays, indigents, souls in fur. Brown’s favorite channels the spirit of Veronica Franco. Veronica Franco or Marie Duplessis. She is orange, small, and elegant, a golden Lab–beagle mix. He does not know why she visits. He does not feed her, and she is not his dog.

LXXXVIII

Nothing more casual than a cow. A stained sweatshirt for eyes. Mud-lathed, scuff-marked hocks. A breathing, edible log. Unassuming. Unprepossessed. Bossy. The constable tail swishing flies takes no note signing the pie-plop behind. Sublime nonchalance. A browsing and musing on the verge of sleep. Then annoyance after a nap. A put-upon nun. No jazz in those horns. A cast die for the grass in its extrusion to milk and meat. Also covenant maker. Black Baal smelted of timothy and clover. Sacrifice penned and driven. A bondage. An acropolis. Her language does not sound like but means moo or leave me alone or come hither, calf or holier than thou. Cow. Corn, her Judas and chocolate.

LXXXIX

Coco rings four times and answers herself, “We’re not home right now. Please leave a message after the beep.” And beeps. Then whistles a little—like Nestus Gurley—a note or two that with a note or two would be a tune. And also sharps the beeps of a garbage truck backing up, says, “C’mon,” asks, “How are you?” and answers, “I’m fine. What?” Gray suit, red tail feathers, call girl—whatever you imagined hearing, listen again—if you mean to swing, listen less deeply. Become echo, redux, rain, bark, gear, love cry, and diesel. Exalt. Let go of meaning.

XC

Skink, gram of mania, animated pepper, shadow-monger dressed in panic, monitor of ghostly footfalls, it concentrates in its essential tic the frog leg dropped into oil and the human shock at the verge. If it would stop and let her look, she might imagine the tropic where it hangs in a hammock between two popsicle sticks admiring the iguana’s stealth, but it does not stop. Hawk-dodger, crow-pretzel, gallows’ twitch. Spider-shark. Porter of readiness, miller of the steady shudder, peripatetic rectitude, run by the power of the sunlit rock, it fortifies Darwin and the idea of being late and the missed appointment. With its blue tail, it reminds her: it will go on. It will not stop.

XCI

She made a barrier with a square of hog wire, set it on the lawn above the spot where the blandishing turtle laid her eggs, and marked it with feather and stick—

So he would think to mow around it—and came back and bent down the edges to thwart raccoons. Everything should be made as simple as possible, said Einstein, but no simpler.

What he did out in the world was his own business, with animals, with stocks and bonds, with girls in bars. Not that he was negligent. Only he needed to think.

She did not have to think, all summer watering that place the way she folded cutlery inside napkins and left them at the center of plates for servants.

XCII (Luck Considers the Difficulties of His Art)

The eagle above the house, which on further inspection turned out to be a vulture, remains an eagle in his aria.

For years it has been eagle. To change it back to vulture would only remind him how rarely facts matter.

To the dead, for instance, or philosophers in love with universal likeness.

Wings circle overhead. Rings soar inside a tree. Often, wrote Rilke, angels make no distinction between the dead and living.

Luck sits in the yard and listens. The cardinal must have eaten something remarkable. All it wants to do is sing

XCIII

How quickly they came to their full bodies and never that protean instant of metamorphosis, only one day both were inexplicably large with the downy, white, otherworldly mien of the working children of the Depression Thomas Wolfe described as cottonheads.

But one fluffing up and flexing, leaping and beating its wings, while the other hung back, shadowed and tentative. Perhaps because it had hatched later. Or was that its nature, to watch? The sneak, the thief, who watches and conceals as he had waited in the shadow of his sister.

A few weeks, as May turned to June, he studied them through expensive binoculars, then noted in a cheap black notebook events that stood out: mornings, a parent carrying a snake, thunderstorms, hot nights—and what might have transpired in the back of the nest. Killing lessons, lockings of beaks.

Each day a further emergence, until the one he called Jupiter was boldly venturing along high limbs, and the other, the peeker, who remained unnamed, stepping forth in increments, pausing to check the position of its feet and wings as if monitoring gauges for oil pressure or altitude.

Later, when they had first flown and he had missed it, he grieved, though of course, hawks are not people; flight is what feathers are for; eyases fly—badly at first: aiming to soar, they often dip, then flap, flap desperately to clear the eaves. Yardbirds, they grub two weeks. Luck noted, They apprentice, before becoming hawks, as chickens.

XCIV (Luck and the Coyotes)

What he feared was far off, and what he relished near, so he asked neighbors what they were, and a woman said they were mean, small but tricky creatures. They had lured her daughter’s kitty into the woods, then eaten it. No one could stop them. Like migrants they passed along hedgerows and fence lines, but never directly in front of you, and he had not truly seen them until he found one freshly killed: so large the body, so broad the tail, he could not believe it was real, it was knowledge, but no, he did not know yet. He knew when he heard them singing. Knowledge was not the body, but the singing. O the note and O the theme repeating. And the chorus then, the laughing tears. Rimbaud in the barn in Charleville, the opium blowing Une Saison en Enfer. Coltrane playing outside. The place where she changed. Giant Steps. The truth he heard sometimes and knew false and kept secret because it might be true.

XCV

Moss, exemplary machine of function and beauty, unchanged for forty million years and sponging just enough moisture from the air above the escarpment to form without thought an emerald pallet, how could you care about the pastor of the Rock Springs Holiness Church as he bends and gathers the living proof of faith into an ancient gunnysack? Stepping delicately around your face, a name giver like Adam, he is staid and rational. Because the white of the new Holstein bull’s left side resembles a map of the South American continent, he calls him Atlas. Once a rooster named Genghis Khan pecked out his aunt’s eye. Once a sow named Rosie nursed an orphan puppy. The mule Horatio does not forgive or accuse the tractor. Untrembling, unfearful, and unkind moss, the pastor wonders about you as the signs progress to apocalypse. Hearing a noise late at night, he wakes, circles the house, and, finding nothing but a coon jimmying the lid of a plastic can, remembers, before returning to bed, to refrigerate the serpents he will pass out to the congregation.

XCVI

Mack’s boat comes on fast around the bluffs, so by the time he sees her fishing and cuts the engine, it is already too late to apologize for the twenty-first century.

Clearly he has offended the ancients and is shamed, but as she packs her body under her wings and lifts off, grark, she says blithely, so he takes taunt, and flashes, and yells aiiee.

And turns quickly. And, finding no witness, auditions a number of moot epistemological tropes and unemployed kennings like heron person and great blue human.

But as the pulley of the invisible starts hauling her up and across the lake, grark she calls again, and again he hollers aiiee, and thinks less of her as she alights

in the crown of a dead sycamore and fluffs herself up with regal emphasis, so he will understand their relative positions in the higher order.

XCVII

A young female gray fox in the shadow of the toolshed at the back of the yard chasing then lunging at ghosts.

Who seemed easy with her life and only mildly aloof among rank strangers not even her own kind, trotting near and wheeling to freeze for an instant and hear Brown’s whispered “There, there,” and “Come closer, friend.”

Like wind bristling in a tree. But she is not a friend.

Trapped, drugged, taken in a cage on a truck from the den she had made under the round house by the lake, she wakes the same day in a strange forest by a distant lake.

The rain on her coat is a portal to Wall Street. Her dugs, still strutted with milk for her dead kits, accuse him of a vain complicity.

Men who anthropomorphize the economy as the ice caps shrink.

The currency dealer who weeps at The Fox and the Hound, dry-eyed at his mother’s funeral.

The retired teacher who dresses her cat in a sweater, but will not send her daughter $600.

This, too, Doctor Charm, Madam Tenderness, George Brown.

Things see you coming. Don’t baby-talk the monkey.

XCVIII

The opossum, that prehistoric pocket isolette, when headlit, shuts like a politician who shifts topics on being asked a leading question.

Or becomes a hip postmodern possum, her deadpan lump undertaken on the lam, her role of a lifetime nailing a lesser actress attempting her shining self.

A bump where swamp and freeway intersect, Wednesday, a jot past midnight, car-crossed, moon-washed, the instant passing like a wand across a blacktop that was voted on.

And then it lies so still, unmaking beginning as Brown heads uphill. A closed water park. Joe’s Imperial Boom City! And farther, going little towns of operettas and pretty-baby pageants. Apolitical

miles between American cities, neither pepper nor salt, where Brown tries not to veer as he considers dinner options: perhaps some golden fries, some fish, and still no exit that is not opossum.

XCIX (Portis and the Doe)

One of the deeply shy, one of the abject and baffled, just before twilight she appeared not twenty feet from him, looked him in the eye, and hightailed it back into the trees. Then he remembered how she had come to him first as a human being. Afraid, incoherent, drunk, she had just snapped on the light, stumbled to his bed, and shaken him awake. There, yet not there. Wrong, wrong, wrong, he remembers thinking. The head swayed, wild eyes stared down at him. Then she screamed, “Asshole, you’re not even him!” And disappeared. The room was iron. The smell of whiskey hung there like a beard. Oh, he knew her all right: the candor of her body—the wilderness of her mind justified high fences. But who was he? What kind of animal?

(1974–2015)

CX

One place is as good as another to be born

and return after years, like Odysseus to Ithaca or mildew to a rotting plank.

How Sunday it all looks now, paved and pastured, fieldless and storeless.

Burglar music. Late morning. No one home.

And the past, still and under: its sawdust ice, its milk jugs screwed tight and suspended

in spring water.

County life, pre-telephone, without verbs.

Small houses, a quarter of a mile apart, of whitewashed or unpainted clapboard, each

with a well and outhouse.

Larger houses with barns, chicken coops, toolsheds, and smokehouses. Hounds of

some significance. Men. Women. Children.

Nary and tarnation. A singing from the fields. A geeing and hawing.

A voice here and there with a smidgeon of Euclid and a soupçon of Cicero to hifalute

what twanged from across the fence and the other side of the bucksaw.

Each day of 1953 like a pupa in a chrysalis.

Phenomenology buzzing like wasps in the stripped timbers of the gristmill.

The road out busting from trace and logging ruts. Now and then a backfiring

Studebaker with its doggy entourage and roostertails of dust.

But less and less in 1954, a mare and wagon, orbited by a yearling colt.

The evolution of the cabin to dogtrot, the boarding up of the hall between the west

side’s living room, kitchen, and pantry, and the east side’s two bedrooms.

Stone chimneys at each end, and on the porch across it, the kitty-holed door to the

attic’s must, mud daubers, and déjà vu.

A spinning wheel with spavined and missing spokes, a warped sidesaddle, boxes of

wooden tools, gaiters, spectacles, dried gloves, shoe lasts, letters from dead to dead.

The cellar beneath it all. Wooden casks, wine bottles dusky and obsolesced by the

hardshell feminism of the great Protestant reawakening

that quarried legions of infidels from saloons and brothels and restored them to their

families. Portis’s own.

Tom Portis’s vineyard east of the house, his vines of small sour grapes still strung with

rusted baling wire to rotting posts.

His continuance bolstered and intensified should a client void a decade and show up

early morning, stumble-drunk, moaning, “Virgie, Virgie.”

Prose fragments.

The smokehouse. Hams, shoulders, and side meat interred in separate salt bins.

The hog lot.

The well into which, it has been told, Portis once dropped a Persian cat.

And what is the name of the cat? And what word now from the after?

Here are some verbs: woke, saw, stretched, heard, washed, smelled, sat, blessed, ate,

listened, rose, waited, walked, felt, shat, dug, meditated, buried, gone

though somewhere, perhaps by some odd fractal of the principle of the conservation of

matter, a remnant of the original template holds.

Home odor, unreconstructed, peasant, third world—

“Nostalgia for the infinite,” the nearly forgotten Bob Watson called it.

Maybe it’s just like that. Maybe it’s exactly what they say

after years to the old when they were children.

(1992–2009)

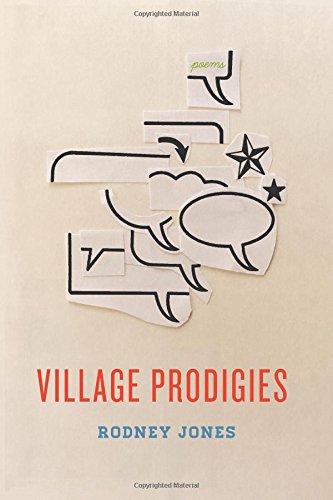

“Only the Animals are Real” from VILLAGE PRODIGIES by Rodney Jones. Copyright © 2017 by Rodney Jones. Used by permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. All rights reserved.