Vanessa Hua on Writing About the Forgotten Women in Mao’s Inner Circle

The Author of Forbidden City Talks to Jane Ciabattari

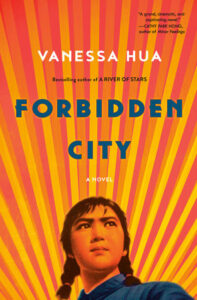

Vanessa Hua’s Forbidden City is narrated by a courageous, risk-taking sixteen-year-old whose life in a small village in China is up-ended when she is selected to join an elite dance troupe of young women trained in ballroom dancing to entertain Party leaders, including the Chairman. Hua’s is a fresh feminist take on the Cultural Revolution, an intriguing perspective on a complicated historic period still partially in the shadows.

Hua, a San Francisco Chronicle columnist, is also the author of the novel A River of Stars and a story collection Deceit and Other Possibilities Her honors include a Rona Jaffe Foundation Writers’ Award, a Steinbeck Fellowship in Creative Writing, and an NEA fellowship.

Our email conversation took place during the week that supply chain issues which had delayed the novel’s publication twice were resolved.

*

Jane Ciabattari: How have you managed during the tumultuous and uncertain last few years? Writing? Family? Community? Work?

Vanessa Hua: I’m the mother of twin sons, who were in the third grade when the pandemic hit in the spring of 2020. We also live with my elderly mother, three generations under one roof. For months, my husband and I juggled their zoom school and our remote work while taking care of our families. It was extremely challenging and frustrating, though I also knew we were fortunate, compared to what others struggled through.

I stayed up late doom-scrolling far too often—and still do. As an antidote to the digital, I became a forager, something I’d always wanted to learn how to do. I consulted guides to identify flowers and plants on all our walks. The practice helped me stay present and grounded, and sharpened my gaze on the world. I’m also grateful to the friends I connected with, at first virtually, and later on, joyously outdoors.

JC: In your Author’s Note you mention Zhang Yufeng, who was eighteen when she first met the Chairman, who was then in his late sixties. She became a mistress of Mao and his “confidential clerk.” Toward the end of his life, you note, “as his speech became garbled by illness, she served an important role, interpreting what he said.” What inspired you to write this novel of a young woman who becomes enmeshed in the Cultural Revolution in China through a relationship with the Chairman?

VH: Years ago, I was watching a documentary about China and up popped a photo of Chairman Mao surrounded by giggling teenage girls, dressed like Bobby Soxers. I was astonished! It turned out he was a fan of ballroom dancing and special troupes of young women partnered with him on the dance floor and in the bedroom.

In his memoir, the Chairman’s physician, Li Zhisui, called the experience for these young women “exhilarating”—but I knew it had to be more complicated! What was it like for a girl to meet Mao, after she’d been raised to believe he was a god?

JC: To what extent is this real figure in the Chairman’s life the model for your narrator, Mei Xiang, who meets the chairman in 1965, at sixteen, after being plucked from her village by Secretary Sun, summoned to Beijing to “serve the Party” by moving into the Lake Palaces—a “forbidden city”—where the Chairman lived. And who travels the country as a model revolutionary at one point?

VH: Zhang Yufeng was the most prominent of Mao’s real-life clerks/nurses/companions, who traveled with him when he frequently left the capital, but there many others over the years. Yet nothing I researched revealed the rhythms of their daily life together and what went on behind closed doors.

Both Mao and the character he inspired in my novel—the Chairman—are revered, beloved but also isolated and lonely, and in my protagonist, Mei, I wanted to portray someone who wouldn’t even merit a footnote in official accounts yet nonetheless influenced the course of history. The young women who ended up in the inner circle—and had the smarts to keep their place beside the Great Leader—intrigued me, but Mei is born from my imagination.

JC: Did you base the young women who “served the Party” by being dance partners and bed partners with cadres, including the Chairman, on a real practice at the time of the Cultural Revolution? And the rivalries among them?

VH: Young dancers from various cultural work troupes served Mao. I didn’t read any first-hand accounts, but I’m certain there were rivalries. I’ve been a teenager myself, and I’ve closely studied dynamics that can arise among women—among all people, to be honest—when they want the same thing. The Cultural Revolution, for all its grand ideals, became an excuse to seek revenge and settle scores between neighbors, students, and teachers, and the bitter power struggle in the troupe mirrors what unfolds elsewhere in the country.

I wanted to portray someone who wouldn’t even merit a footnote in official accounts yet nonetheless influenced the course of history

JC: How has your career as a journalist shaped your research for this novel? How much time did you spend in China, and in which areas? What were the best sources for information about the Chairman of the Chinese Communist Party Mao Zedong, Madame Mao, the President, Defense Minister, and others in power during this time?

VH: For nearly a quarter century, I’ve been writing about Asia and the diaspora. I’m also the American-born daughter of Chinese immigrants, and I’ve long been fascinated by the history and culture of my ancestral homeland. My parents, born in the 1930s in China, moved around frequently, ahead of Japanese invaders and later on, during the civil war, before leaving for the island of Taiwan as the Communists came to power.

I first traveled to China in 2004, to the Pearl River Delta outside of Hong Kong, writing about the economic rise, going to villages and factories and meeting teenagers who left home to make a bigger life for themselves. I returned in 2008 to research my novel, conducting interviews in villages outside of Beijing, as well as explored the Forbidden City, Tiananmen Square and the Great Hall of the People, the high red walls of Zhongnanhai, Shanghai, and Hong Kong, in part tracing the path that would become Mei’s.

Nonfiction sources I consulted included Li Zhisui’s The Private Life of Chairman Mao, Frank Dikötter’s The Cultural Revolution: A People’s History, 1962-1976, Yang Jisheng’s Tombstone: The Great Chinese Famine, 1958-1962, Feng Jicai’s Voices from the Whirlwind, Michael Schoenhals and Roderick MacFarquhar’s Mao’s Last Revolution, Alexander Pantsov and Steven I. Levine’s Mao: The Real Story, and Edgar Snow’s Red Star Over China, as well as newspaper archives. Those accounts chronicle those in power, and with my novel, I wanted to examine where the official record ended.

JC: Did Mao (like the Chairman) have a deteriorating disease toward the end of his life? If so, can you give details? And was this kept secret from the public? I’ve seen reports that he suffered from Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (motor neuron disease) in his later years.)

VH: Yes, multiple sources cite a diagnosis of Lou Gehrig’s disease (ALS)—Mao: The Unknown Story, and Mao: The Real Story and The Private Life of Chairman Mao. Western news reports at the time also thought it was Parkinson’s—I don’t believe it was widely known, in part because he really wasn’t seen much in public except to wave from high above the crowds. In my novel, the Chairman has a neurological movement disorder, but it’s not a specific diagnosis.

JC: What are the various meanings to your title, Forbidden City? Were you able to visit the location? And talk to people who had spent time there?

VH: For centuries, the Forbidden City was home to emperors and the political and ritual center of the country. It became a museum in 1925. But Zhongnanhai, the pleasure gardens adjacent to the Forbidden City, became the country’s seat of power where Mao and other elite lived and in a sense, became the new Forbidden City, with its power, secrecy, and isolation from the world unchanged.

It has gardens and man-made lakes, surrounded by high red walls. Since the public no longer has access to its grounds, I relied on written accounts, photos, and Mao’s physician also includes a map in his memoir. By visiting the Summer Palace, the Forbidden City, and traditional Chinese gardens, I devised what appears in my novel.

But the Forbidden City is also a metaphor, that refers to the Chairman himself, the Great Leader whom Mei circles and circles, trying to find a way in.

JC: Many in the older generation who survived the time of the Cultural Revolution have been loathe to speak about it, even to family members. Why do you think that is? Because the habit of not criticizing was engrained? Because summoning up memories was too painful? Or?

VH: The reasons may vary, since no community, no generation is a monolith. Some might have preferred to focus on the future, rather than a painful past; others might have worried about the consequences of speaking out. But I suspect it also has to do with an incomplete reckoning about the violence of those times and the role of Mao. To attack Mao was to attack China itself; it would have undermined the ideological underpinnings of the country.

Gereme Barmé’s Shades of Mao: The Posthumous Cult of the Great Leader is fascinating, detailing how—in the late 1980s, when people were frustrated with the Party’s pace of reform—turned nostalgic about this sage-king, this wily fighter. Mao is reportedly popular among Gen Z in China; his teachings about class and capitalism economic inequality resonate with them, even though they were born decades after his death in 1976.

JC: You mention that you began writing Forbidden City a decade and a half ago. What have been major steps along the way? At what point did you discover Mei’s voice and make her experience central to the narrative? What made you decide to have Mei become so close to the Chairman, and then become disillusioned?

VH: In 2007, haunted by the photo of Mao surrounded by fawning young women, I wrote a short story set at a dance party. The characters kept tugging at me, though, and I worked on the novel in UC Riverside’s MFA program. After graduation, I landed an agent and the novel went out on submission. It came close, but didn’t sell, which was devastating.

In that iteration, the 1970s Chinatown plotline was perhaps 30 percent of the novel, I expanded it in another draft, cut it away entirely, and eventually settled upon it as a framing device. There were just too many characters, too many subplots.

Though I worked on other books—Deceit and Other Possibilities and A River of Stars—I kept returning to Mei and her story. I couldn’t quit it! I was so grateful when my new agents were able to sell the project.

Mao is reportedly popular among Gen Z in China; his teachings about class and capitalism economic inequality resonate with them, even though they were born decades after his death in 1976.

Even though I eliminated most of Chinatown, having it bookend the novel allows for Mei’s retrospective voice, a decade after she met the Chairman. With his death, she can reckon with what happened, and see what she couldn’t at first, as a teenager. She was so very young, as were many of the Red Guard in the Cultural Revolution who were swept up into the idealism and the violence of those times.

JC: Mei directs her narrative to a person she calls “you” for much of the book. At what point did you decide on this approach? (I’m not going to indulge in a “spoiler” here, but when I came to the point where “you” became clear, I found it incredibly moving.)

VH: I’m so glad it resonated with you! I didn’t take this approach until late in the lifespan of the project, sometime after its sale in 2016. I’m not sure what inspired me to experiment with it, but once I understood who she was telling the story to, why she needed to tell it now, it added urgency and depth to my novel. It felt like I’d sunk a key into a lock, and tumblers started to turn.

JC: How is writing a novel different for you than writing short stories, which you’ve also done with great success (your collection Deceit and Other Possibilities received an Asian/Pacific American Award in Literature)?

VH: My two novels began as short stories, probably because I couldn’t get my head around sitting down at my desk and telling myself, “Today I’m going to start a three-hundred-page project that will take years to finish!” That’s not to say that all novels are long short stories, or that every short story should turn into a novel. I love short stories, and how their endings continue to resonate, giving off a sense of possibility. By the end of a novel—the writer and reader—have been on a journey that arrives at The End (which, I must say, is one of the more exhilarating moments in a novel draft, when I typed that in.)

Writing a novel is a years-long process, whereas stories generally take months or a year or two. That said, I started my short story, “Room at the Table.” in college and didn’t finish it until more than two decades later.

When awaiting feedback on various drafts of a novel, I’ll work on essays or short stories. The different forms nourish my creativity.

JC: What are you working on next? More stories? Another novel?

VH: I’m working on a new novel, examining the nature of loss, displacement, and encroachment. Of territory, of predators and prey, of insiders and outsiders. Of surveillance and security. I’m very excited about it! I’m also contemplating an essay collection, but it’s in the very early stages.

____________________________________________________

Vanessa Hua’s Forbidden City is available now via Ballantine Books.

Jane Ciabattari

Jane Ciabattari, author of the short story collection Stealing the Fire, is a former National Book Critics Circle president (and current NBCC vice president/events), and a member of the Writers Grotto. Her reviews, interviews and cultural criticism have appeared in NPR, BBC Culture, the New York Times Book Review, the Guardian, Bookforum, Paris Review, the Washington Post, Boston Globe, and the Los Angeles Times, among other publications.