Vanessa A. Bee on How Writers Can Make Rejection Work For Them

“Let them channel that spiteful energy into their work, if spiteful energy is the fuel they need to unlock their full potential.”

The first time I remember performing out of spite was in high school. I was thirteen years old and a fresh transplant to Reno, Nevada. My mother and I had spent the previous three years in England, and the decade before that in France. I arrived with a strange little accent and none of the foundational cultural references that bound my new classmates, from Dr. Seuss to Oregon Trail to the total experience of middle school. But most importantly, confusion among the adults in charge of my schooling caused me to accidentally skip a grade. (British “Year Eight,” which I had just completed, corresponded to the American seventh grade.)

The administrative mishap stung me most in geometry class, a prerequisite course for ninth-graders who intended to take Advanced Placement (AP) calculus exams as upperclassmen. Our teacher, Mr. N., opened the fall semester of 2002 with a reminder that a minimum score of 3 out of 5 on the AP exam was required to earn college credit. The warning made clear that his class was not just a sanctuary for teens who enjoyed math. It also served to weed out those who could not hack it. Underscoring this point, Mr. N. announced that in the spring he would predict our individual scores on the AP calculus exam. Students with a prediction of 2 or below should consider less challenging classes.

If Mr. N. was unwilling to bet on me, then I would bet on me.

Enrolling me in the pre-AP program was my mother and uncle’s idea. I, for one, would have been perfectly happy with coasting academically while I adjusted to this new social universe. Despite the significant risk of being labeled a nerd at such a critical juncture, I went along with the family plan. Until then school had been a breeze. I would figure it out; I always did.

But months into freshman year, solving for x still felt like scaling a mountainside. I envied those to whom the theorems came naturally, and wondered if my struggle meant that I was simply not a “math person.” Despite receiving homework help from my uncle, an engineer trained at Texas A&M, the best grade I could summon that first semester was a D—my closest brush with failure at the time. I remember attacking the spring with a renewed drive. Although my final grade was nowhere near the top of the class, I ended the year with a firm grasp of the material. Nonetheless, Mr. N. showed me the door with a predicted 2.

I am fairly certain that I cried that night, humiliated by his assessment of my potential. But by the end of summer, a kind of determined spite had replaced whatever blues I felt. I refused to be boxed like some equation with an immovable answer. If Mr. N. was unwilling to bet on me, then I would bet on me. The next year, I enrolled in advanced algebra, followed by trigonometry, and finally, calculus. Few things satisfy me more than picturing the utter disappointment on Mr. N.’s face, the day he learned that I scored a 4 on the AP exam.

After high school, I rarely thought about Mr. N. until I began working on a memoir in late 2018. The endeavor took me by surprise. One moment, I was a person who loved experimenting with form but harbored no desire to birth a book. Next, I was chiseling drafts of personal essays at dawn and revisiting them at night, after full days at my regular job. This book needed to contextualize facts and unravel their effects. It needed to be honest, unsparing but compassionate. I also wished for its stories to bring its intended audience as much pleasure as a fine meal. It was not enough to write a book. I wanted to create an object that felt like art, at least to me.

Their message towards me was clear. I did not deserve a spot on the gatekeepers’ shelves. I did not warrant their investment.

Soon, I had a 60,000-word book proposal and instructions from my literary agent to pitch pieces widely, in order to build my credibility as a debut author. I sent out original ideas but also tried to place excerpts of the memoir with editors in the demographic with whom I hoped the book would resonate. More often than not, these editors either ignored my pitches or passed on them. I felt like they were reading my work and predicting a 2 out of 5. Still, I reminded myself that silence and outright rejection are par for the course. Besides, this was emotional prep for the real upcoming test: submitting a full book proposal to publishers.

The experience proved brutal. More than thirty book editors passed on Home Bound in the fall of 2020. Some had worked on books I admired, which was disappointing. And a subset were Black editors, sometimes at imprints that had vowed to champion more Black voices, after a wave of protests that followed George Floyd’s murder recast the spotlight on the industry’s treatment of Black publishing professionals and writers.

I tried to internalize my agent’s wisdom—we only needed one yes, the right yes. Still, the slew of no’s catapulted me back to ninth grade. To be clear, I do not doubt these editors’ commitment to supporting more Black authors. But their message towards me was clear. I did not deserve a spot on the gatekeepers’ shelves. I did not warrant their investment. I did not show promise. Or maybe I was not the right kind of Black author, whatever ‘right’ meant. I felt that wave of sadness again.

But then I got lucky. My manuscript went to auction and found a wonderful home at Astra House. I buried these feelings of inadequacy in a deep well and focused on completing the project. There were still whole chapters to write, astute editing notes to incorporate, and always, always, more copy editing. I often found motivation enough in the idea of creating art for art’s sake. But publishing is a marathon and by the third year of writing this book, I was still inching toward the finish line.

I felt the determination to prove wrong each of the editors who rejected me. Indeed, there were times the only progress I made was buoyed by the desire to write a book so compelling that any editor who ever underestimated me would regret it. I carried the thirty-plus rejections in a figurative fanny pack that I brought to my writing practice with the same determination that made me hold on to Mr. N.’s prediction until the AP Calculus exam. I allowed myself to feel anger, and its natural companion, spite, as often as needed to get through the last edits.

I admit that fear played a part, fear that gracefully accepting the possibility that my work did not merit publishing would erode my ability to be free on the page. And so I thought of my legion of rejectors many times in the year after selling my manuscript. I thought of them as I turned in the final version. And here I am again, as Home Bound sets to enter the world, wondering if I have met my goal of putting out a work that will make my rejectors wish they could rewind time to claim me.

It is a strange world in which writers must be above it all—a world where writers are expected to demure on how being overlooked really made them feel.

I realize how spoiled, or even unhinged, this may sound. Although their rejections fueled my writing, I am not so unreasonable as to actually bear personal ill will toward any of these book editors. Culling is part of the job, which is itself subject to capitalism and all its pressures. These editors must do it, as must mine. So why allot an ounce of concern to people who will never remember my name, let alone passing on my manuscript? Why not simply delight in the fact that a publisher ultimately saw worth in my project, an outcome that is far from guaranteed to any writer? (To be clear, I do.)

I know that it would much more dignified to let my little fanny pack of rejections go. At the same time, it is a strange world in which writers must be above it all—a world where writers are expected to demure on how being overlooked really made them feel, because there is something inherently embarrassing about the anger, disappointment, or outright sadness that grounded their motivation after being rejected.

Maybe the trouble is these emotions’ rooting in a place of pride. To feel them out loud is to reveal a sincere belief in the worth of the work and in oneself. It is a refusal to perform false modesty. But what if the alternative does not serve the work?

Rejection, however gentle and however valid, is still rejection. I think writers should be permitted to take it personally, and to be open about it, when so much of writing is personal. Let them channel that spiteful energy into their work, if spiteful energy is the fuel they need to unlock their full potential. Certainly, I did. Perhaps this admission is beneath me, a failure to demonstrate humility. But this is how I bet on myself. And I know my book is the better for it.

_____________________________________

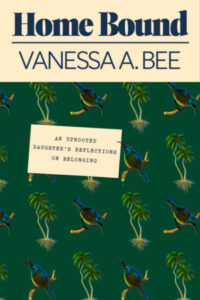

Home Bound: An Uprooted Daughter’s Reflections on Belonging by Vanessa A. Bee is available from Astra House.

Vanessa A. Bee

Vanessa A. Bee is a consumer protection lawyer and essayist. Born in Cameroon, she grew up inFrance, England, and the United States. Vanessa holds an undergraduate degree from theUniversity of Nevada and a law degree from Harvard. She lives in Washington, DC. Follow @Vanessa_ABee on Twitter and @TheHomeBoundBook on Instagram.