Dear Wura,

I remember when you asked me if I’d been in love before. I said, Yes, a few times. I jokingly started with the one about my childhood crush, the girl I proposed to with a blade of grass at the back of my primary school. We called each other husband and wife for a whole year and were inseparable. I believed that was love then, so I said that one as a joke. I don’t even remember her name. The heartbreaks after her were way more tragic and way less funny on my side and on theirs. They changed me, and so I thought . . . of course I was in love, of course. How could I have felt that much pain if I wasn’t? But I was thinking about it again today and I asked myself if I am sure.

I mean, I loved a woman in my early teens, yes. But she was too adult to be “loving” me. She flipped me upside down in my attachment to her. She would be there intensely, then disappear for weeks. Like that, on loop. It ran me noticeably mad. When my parents found out, they didn’t confront me. One look at her and they were sure she would destroy my life. They reached out to her behind my back, each with bundles of naira in one hand and a threat in the other. She accepted the payment and moved out of the country. I always believed she upped and left, so she was the first person I ever hated. But I found out the truth by some twisted means when I turned twenty, and everything I thought I knew about my family quaked in that finding. It took me a long, long time to realize that that was a salvation; and that that was a “love” that should never have happened. She should never have turned toward me like that in the first place. She was old enough to know better. And she did.

In my twenties, I dated a woman who was older than me by a decade. Our relationship was intense, to say the least. She was a woman who always showed, even when she didn’t mean to. It annoyed her that people could take just one look at her and know that she wasn’t there for men. We rarely ever went anywhere public together because there was no way to look at both of us, each wearing trousers, and think just friends. She hated it so much, that loud visibility, but I don’t think I understood how much until she came home one day with a ring on her finger. When I asked her about it, she told me that her boyfriend had proposed. I didn’t even know she had a boyfriend.

Neither did I know she was seeing anyone seriously enough to get married. Where did he come from, who is he, how long has it been, are you really going to marry him? I rolled all those questions in her direction. Yes, she said, I’m going to, but chill, you’re acting crazy, calm down, he’s just a man. It hurt, but it wasn’t a dealbreaker for me. It was true: He was just a man, and what did men know? What could a man do better than me? Not much. I could stay as long as she still loved me, I decided. Then her husband found out. Things between us got darkly quiet soon after, in the way secrets of this shade can do. Was that love, or a rest stop?

Then there was my ex-wife, who you know the most about, the one I was too sore to give more details about. The one I was sure of. We were together by date two; quickfire. By the sixth month, while we were traveling together, she said: Let’s get married. There was no ring involved. We committed to each other in a small court in a “progressive” country, and we went to an all-women’s nightclub after. When that holiday was over, we came back to Nigeria. We knew what we were, so it didn’t matter if nobody else did, if people looked at us and saw friends, or sometimes even sisters. What did I care? My baby was mine. That’s all I needed. I’d done without my family for long enough (you already know that story), so I didn’t have to explain a thing when I moved in with her.

But there are parts of the story I left out. Our relationship was about hiding, from the start. You know, for women who come from homes like ours, we have two options. You grew up with money, and you can’t fall below your class, so to keep that status you either have to become just as powerful as the men in your field (so that you’re just as respected as one) or you have to marry a strong name. You’re not supposed to drop the baton. Because both of us knew we would rather die than marry men, we had to compromise somehow; we owed our families that. So we decided to become the sons our fathers never had. Me out of spite, and she out of love.

She faced politics and I faced economics. She had way more practice than I did at that performance: her father’s gift to her, for her twenty-first, was her first bodymask. You are stronger than five men, he said, grinning. He got a skin sculptor to make it. It will be believable, her father said, if you just follow the script. When you go out, wear the mask; when you come home, what you look like or are is between you and your God. Can you do that for me? She didn’t need to weigh the options. Her father already had his hand deep in the national cake; all she needed to do was show up. He kept his word and took her everywhere, introduced her to all his contacts as his child, his first, his right hand. No one could say shit.

She taught me that you don’t have to be a man if you can talk, touch, act, or look like one; you just have to masquerade as one. Anybody can be a powerful Nigerian man, she told me. All it takes is believing you deserve a good life and pursuing it relentlessly, even if it means running over everyone else. You need great suits, a large ego, a solid network, a strong voice, and some fuck-you money. Why, because na money be oga, na money be sir. Na money be senior. Na money be man. And men, as thick as they like to pretend to be, know better than to argue with their seniors. With my father on our side, we are everybody’s senior.

She wasn’t joking. So: this is how to knot a tie, this is how to talk to women, this is how to enter a room and seize the air in it. She was the father I never had—sliding my business card across cold tables, insisting on my name in strong rooms. To be honest? It was an un-beatable rush. Side by side, we became better at being men than they were. When we showed up to events, powerful men stood up from their seats to greet us. Oh no, they used to say, avoiding our eyes. Please, gentlemen. It’s my pleasure. One day, her father called her with a warning: Listen, I don’t care who you love, I care what you do. I care about the mark you leave. Get the money, make the name, set up your life—and you can move abroad if that’s the lifestyle after your heart. But until you reach that goal, know what you’re doing. Know who you’re allowing into your home so that it doesn’t get out. You understand? She said yes. All of this is politics, she used to say, and in politics, you have to be as ruthless as you can just to get what you want. And I’m so close. I’m so close.

I didn’t mind. I loved that her father didn’t hate me or us. I loved that I was the only one who knew her inside out. It swelled my pride. When she came back home, I was the one standing behind her, unclasping the mask from the neck, unzipping the body down the back, watching it fall to the floor. We took turns washing the body and drying it, every weekend. In my workplace I became just as good as her. The first day I wore a bodymask, it was like a visibility suit: everyone saw me with respect. She got it for me as a gift. Sometimes, when men pissed us off, the power sped to our hearts and we didn’t rest until we’d fucked their frustrated wives and given them what their husbands hadn’t in years. We’d fist-bump, thump each other’s backs in praise like the beautiful bastards we were. Those moments were rehearsals for moments with our peers, our fellow painful rascals. When we got bored of that life, we’d kneel in front of each other in bed, each helping the other unclasp our masks, peeling the sleeves off, unfastening our outside faces, locating each other’s mouths. In a matter of minutes, we’d become the tenderest things. We never let those other women see us like this, we never ever let them touch us. We liked that they thought we were stone, and that at home, next to each other, we were soft rock, spilling sweetwater.

It lasted until it didn’t. Things moved fast. Elections coming close, her father getting older, her fear about him dying or even worse, him being alive and watching her lose. She went harder, put her back into it. Everything was about winning. I saw her become colder, saw her begin to refuse—more and more—to take the act off when she entered the house. She started sleeping in our bed with her outside body and mouth. Her beard scratched against me when we kissed. But did I care? It was only for a time.

We went on like that, passing time, waiting. She won the election and got her seat. She got us the life, but it crushed us. When they give you the masks, they advise you to take them off when you can, but they don’t tell you why. They should, though. They should tell you that if you don’t take breaks from your acting, the false skin will grow on you; that you might have to sit down and the mask chew off your lover’s face. It’s only right.

After she won, she came home tired and triumphant. Around the time when they were discussing the SSMPA Bill, we talked about it. You have to stand against it, I said. She told me it was not that easy. I can’t afford that focus on me, she said. Remember what my father said about discretion. I said, Okay, babe, but is this still acting? I haven’t seen you in so long. She said, I’m here.

God knows how long we spent arguing. I finally convinced her to take it off for that one night. When she turned around and I tried to undo that clasp and we couldn’t lift it without it snagging at her, without peeling skin and drawing blood, I knew. She turned to look at me and we didn’t need to say anything. We ended it. Her father died soon after. She fled the country, dropped the job and relocated to America. I found out on Facebook that she has a wife and two kids now. In the pictures, she looked like herself, the her before all the masking. She made the right choice moving, reverting, because I know for a fact that it can kill a person to become and remain the exact thing they’ve always feared.

__________________________________

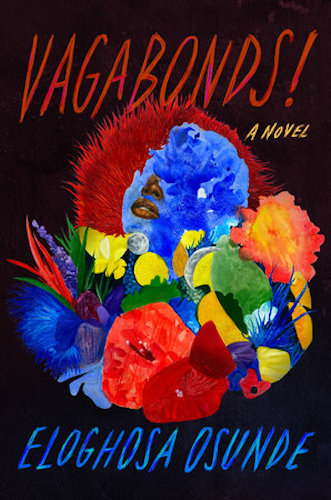

Excerpted from Vagabonds! by Eloghosa Osunde. Published by Riverhead Books. Copyright © 2022. All rights reserved.