Before we were born, the land our parents worked in Illinois had value. The export of wheat and soybeans nearly tripled during those years thanks to the wheat deal with the Soviets, who paid millions for bushels. Before we were born, our father redid the floors, a room-by-room project meant to keep his evenings busy and temper his drinking, an issue even in those days. The ladder leading up to the small attic space needed repairing, like everything needed repairing. Time and time again, our father said he would repair the ladder, toilet, oven, the roof of the barn, but he never managed to get around to it. Instead, he would drink too much, get angry, build an outhouse, and begin saving to buy concrete for what would eventually become our driveway.

Sylvia, our mother, reminded Henry daily, such was the routine of marriage, about fixing the ladder daily and went about partitioning the attic space, figuring if they were to have children, they would need a place to store them. Sylvia built the walls herself, delineating two iffy bedroom-like spaces in the attic. And, with the help of the plumber in town, she built a tiny half-bath. She updated the curtains, sewn from old sheets she had found, painted the walls Kelly green, and pinned up pieces of mismatched scraps of wallpaper to add dimension.

As was often the case with children, before the two of us came along the future was bright. “Life potential was a cherry orchard,” Henry would say, before telling us little fools about how we had really taken the best from them. Before we came along to ruin everything, there was this rare and fleeting time where our parents had room to grow and to travel locally and in their minds. Our parents would reminisce about their past happiness and point to the oversized photographic portrait taken of them at the county fair sometime in the mid-1970s, before we were born.

The large portrait, taken at the county fair, served as a document, proof, if you will, perhaps even a reminder of this rare and fleeting time before my sister and I existed. It also represented an annual tradition, a symbol of a break from the often lonely, arduous daily rituals, a reminder of the long history of rural communities coming together to collectively build recreational spaces. Jo liked to say of the portrait that it reminded her of an execution line-up. I remember pointing out that by and large our parents looked sedate. I told her that prisoners could be subjected to maltreatment, including starvation, and therefore would not look sedate. We agreed their smiles looked forced. It was not how our parents smiled, but more to the point: nobody wanted to be remembered as miserable. Nobody knew what to do with misery in photographs. No person would hang a giant portrait of futureless people—especially those who knew that they would never travel outside of the Midwest—in their living room. Or even a small one on their fridge for that matter. There were far too many reminders of misery such as it was. Furthermore, nobody getting their portrait taken was ever directed to be who they really were, to express what they were really feeling, because what would be the point in commemorating that?

The 20×30-inch monstrosity hung unsteadily above the couch in our small and crowded living room as a warning, I always thought. “As a mnemonic,” was Jo’s thinking. Nothing about the poor quality of the slanted portrait of our parents at the county fair was subtle. In it, our parents pose side-by-side, while behind them is a painted backdrop depicting California’s luscious San Fernando Valley. Each of them carried in one hand a bright orange and showcased the fruit like showcasing a box of jewels. Their other arm was around the other’s waist, their hair is combed, and their expressions appear obliging and alert, ready for the shot. Henry looked straight at the camera, struggling to produce a half-smile. (He wasn’t a fan of being photographed.) Sylvia was suspicious of the lens, but she was complicit with its requests. Our mother, like all the women in our family, knew a thing or two about being scrutinized such that she made a point to tell us not to hide.

Sylvia liked to tell us that Simone de Beauvoir argued that woman was a man’s concept, a concept meaning other, because man was the seer. He was the subject, and she was the object. I remember her telling us to be unafraid of what we wanted—to reach for even our breath. I remember asking if we could get out of the house, out of the town, small even though it had been all I had ever known, to take a family trip to the Quad Cities, or go to the fancy grocery store there to buy something that had not been grown in the Midwest, something as standard and affordable and basic but exotic to us like avocados. Why? Because I was deficient. I wanted health. I wanted to taste something punchy to mask the filth inside. I wanted access to vitamins, like on the television. I wanted luscious hair. I wanted to feel a truly American kind of clean.

“Please can we buy vitamins,” I remember pleading with our parents, who said if giving me vitamins would mean I would go away then they would do it, but nothing was that simple, not even me. If they could have set me on a sailboat with a little suitcase, some books, and a wool blanket, some cans of food and a can opener, and put me out to sea before I had the chance to do it of my own accord, I believe they would have. (The nearest body of water was the Mississippi River, a twenty-five or so minute drive, which would have required the use of the truck and therefore the gas, which was another factor to consider when making a big decision.)

__________________________________

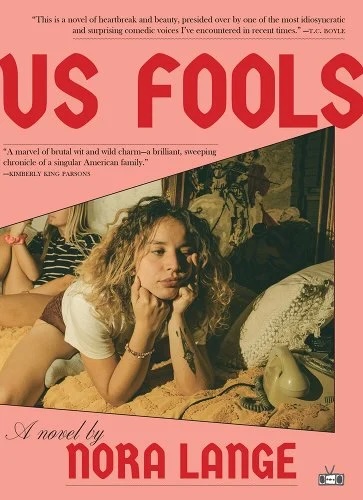

From Us Fools by Nora Lange. Used with permission of the publisher, Two Dollar Radio. Copyright © 2024 by Nora Lange.