Urgent Lessons From a Heroic Early AIDS Doctor: On the Legacy of Joseph Sonnabend

Steven W. Thrasher Remembers One of the World’s First AIDS Doctors

It’s not at every memorial where mourners are not just handed a program of the service, but also given a pamphlet on how to have safe gay sex in a time of disease.

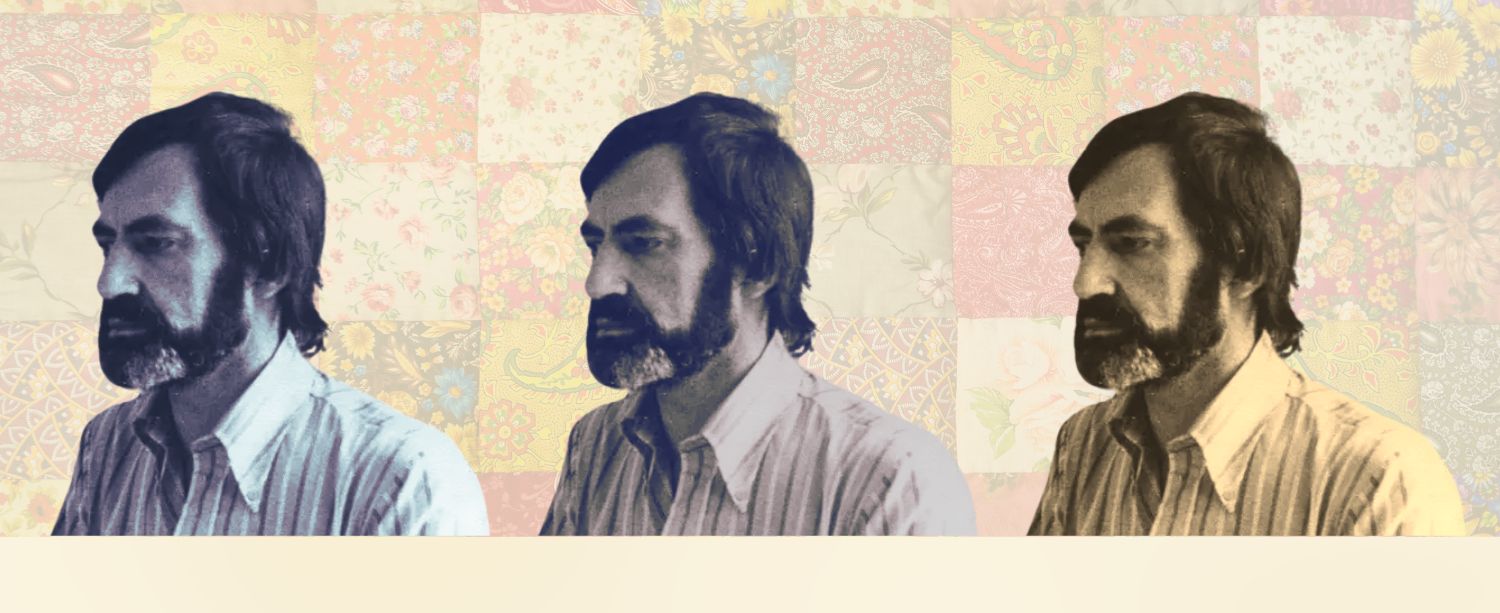

Then again, Joseph Sonnabend (1933-2021) was not just any doctor.

Dr. Sonnabend—or “Joe” as most people eulogizing called him—is often referred to as one of the world’s first AIDS doctors. Born in South Africa, he was trained in medicine, pathology, and virology in South Africa and Scotland, before doing medical research in London and New York. He opened a practice in New York’s Greenwich Village in the late 1970s, where most of his patients were gay men.

Between his regular patients, as well as in his work staffing a free weekly clinic for sexually transmitted infections, Sonnabend was one of the first doctors to not only notice, but to vigorously study, the killer which would first be known as GRID (Gay Related Immune Deficiency) and later known as the Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome.

Sonnabend died in January of 2021, at the height of international Covid restrictions. But on April 13, dozens of his former colleagues, activists, and patients gathered to remember him in words and music. Many were elderly gay men, some frail former patients who survived the plague—and the memorial could well mark the last time so many of the original living ACT UP activists may be together.

Sonnabend had an unusual relationship with the people he treated. “I call them patients,” he wrote, but “they’re friends, really. It’s really hard for me to draw the line” he said, as well as collaborators on his research.

While “How to Have Sex” doesn’t dumb-down scientific concepts or shy from technical language, it is also written for lay readers and created a model of peer-to-peer education.

“Being Jewish I think I’ve got a strong sense of community, of looking after one’s own. And having spent most of my life as a researcher, I never acquired a doctor’s ability to stay detached. There’s no way of switching off from death and misery.”

And though he died at the end of the first Trump administration and his mourners couldn’t gather until the beginning of Trump’s second, the legacy of Sonnabend and his collaborators left couldn’t be more timely right now. From the pamphlet “How to Have Sex in an Epidemic: One Approach” to their scientific work trying to understand what was causing AIDS (and how HIV was exacerbated by social determinants of health) to starting the world’s first patient-led medical advisory board, the lessons from their work is urgent.

*

The memorial was filled with people and markers of history—people who not only shaped medical history in general and AIDS history specifically, but who shaped science and American politics more broadly. One of the most historic of the speakers was Richard Berkowitz, who co-wrote the 40-page pamphlet “How to Have Sex in an Epidemic: One Approach.” As Berkowitz recalled, Sonnabend oversaw the booklet as medical advisor and wrote its introduction. But, importantly, the pamphlet was co-written by Berkowitz and Michael Callen—two AIDs activists without formal medical training who taught themselves, and their communities, about this mysterious new disease. (Callen died of AIDS in 1993; he was just 38 years old.)

The 1983 pamphlet Sonnabend, Callen, and Berkowitz published is significant for multiple reasons. It’s full of scientific information, while admitting one of the truisms of AIDS at the time: no one knew what caused it. It lays out the two leading theories, which both had some truth to them. There was “The New Agent Theory,” which posited that there was a single pathogen causing AIDS which hadn’t yet been discovered (it would be identified as the Human Immunodeficiency Virus a year later); and, there was “The Multifactorial Theory,” which argued that “Rather than occurring after a single exposure to sperm, this theory suggests that the syndrome ‘builds up’ over a period of time and continued exposure to large amounts of cytomegalovirus.”

While the virus in the latter theory, CMV, flourishes because of HIV and does not solely cause AIDS, other elements of the multifactor theory have proven helpful for understanding how AIDS develops, why certain people with HIV become sick faster than others, and which particular opportunistic infections and diseases lead to the collapse of the immune system.

But while “How to Have Sex” doesn’t dumb-down scientific concepts or shy from technical language, it is also written for lay readers and created a model of peer-to-peer education. With sections with clinical names (“How Can I Find Out If I am Contagious for CMV?” and “Learning to Estimate Risk”) to plain slang (“Getting Fucked,” “Closed Circles of Fuck Buddies,” and “Backrooms, Bookstores, Balconies, Meatracks & Tearooms”), the booklet is a landmark moment of harm reduction—the practice of knowing that abstinence from stigmatized but normal human activities (ie, having sex and using substances) is neither realistic nor fair for most people to attempt. But, with a harm-reduction model, if people are given a more dangerous choice and a safer choice, most people will make the safer choice.

Much as some of us found about the 2022 mpox outbreak, community knowledge was key to understanding that whatever led to AIDS had something to do with sperm; AIDS wasn’t causally transmitted through the air (like Covid 19) and, thus, there were safe ways to experience sex, touch and intimacy. In his remarks about Sonnabend, Berkowitz recalled a conversation between people living with AIDS who found themselves to be untouchable and who asked, “Can’t we just jerk off together?” And maybe hug? “How to Have Sex” was not just the model for projects like the 2020 Covid safer sex guide my colleagues at the New York City Department of Health and I helped develop and distribute, but for all manner of harm reduction campaigns over the last four decades.

The skepticism Sonnabend had as scientist was not the hubristic ignorance of someone untrained like Robert Kennedy, Jr.

Another historical element to Sonnabend’s service was that it was held in the Judson Memorial Church, in the very room where the People Living With AIDS caucus was formed, as journalist Andy Humm shared. Much like how medical workers didn’t wear gloves prior to AIDS (they only started doing so in the 1980s when universal protocols were developed to treat all patients as if they were potentially carrying HIV), boards of people living with various diseases and conditions, who collectively weigh in on their care, did not exist before AIDS. PLWA set a new standard of patients being experts on their condition, ensuring that nothing should happen to them without them.

Though he cared for many patients who died of AIDS, Sonnabend also cared for many who lived until the anti-retroviral “AIDS cocktail” treatments were available in 1996. AIDS activist Sean Strub, Yale public health professor Gregg Gonsalves, and artist Jack Waters all spoke of Sonnabend not just as a researcher, but as their personal physician. Strub, who coined the term, “the viral underclass” (which is the title of my first book), spoke about how “Joe’s patients did better and lived longer.” Gonsalves shared how he sent a positive cousin to Sonnabend for care—and recalled how later, Sonnabend made a housecall to deliver Gonsalves’s own positive diagnosis in his home. Waters credited Sonnabend with using a personal medical approach to saving his own life.

And yet despite his legacy, Sonnabend was on the outs for much of his final decades, leaving New York to live out his days in London, unfairly labeled an AIDS-denialist, as playwright Ash Kotak, Dr. Rebecca Pringle-Smith, and Lancet editor Mariam Lewis Smith spoke about. Before the discovery of HIV, Sonnabend (like many scientists) cast a wide net to try to understand what the hell was going on.

But even though he prescribed to the multifactor theory after the discovery of HIV in 1984, he did not deny that HIV led to AIDS; rather, he recognized—correctly—that AIDs is a multi-system, multi-organ failure of the immune system caused by any number of combinations of opportunistic infections and diseases (such as kaposi sarcoma cancer, CMV, pneumonia and tuberculosis). How, why and how severely those various combos develop—as I also argued in The Viral Underclass—is not determined solely by HIV, but by social determinants of health like poverty, racism, homophobia, transphobia, diet, genetics, and environmental pollution. The skepticism Sonnabend had as scientist was not the hubristic ignorance of someone untrained like Robert Kennedy, Jr; he merely kept testing the limits of existing theories and testing new hypotheses in the scientific tradition.

*

The memorial wasn’t important just to an AIDS historian like myself. It is important because Sonnabend’s legacy is not just a historic artifact—it’s a contemporary blueprint. When ACT UP was first raising hell, the Reagan and Bush administrations were openly hostile; and yet, administration officials like Surgeon General C. Everett Coop and National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases director Anthony Fauci were, when pushed, dedicated to taming AIDS.

We have no one in posts like that in the Trump administration. RFK Jr. has been an actual HIV (not to mention vaccine) denialist. The Trump administration has withdrawn from HIV research and prevention broadly, both domestically and internationally. The effects of this have been both immediate (as Nick Kristoff reported, people have already died from a lack of AIDS medication) and will be felt over a long period of time. For instance, most of the research at the Institute of Sexual and Gender Minority Health and Wellbeing at Northwestern University, where I am on the faculty, has been paused or terminated, including a 15-year longitudinal study on HIV in men of color.

When LGBTQ and HIV/AIDS research is halted, the existing health disparities in minoritized communities will grow, more people will get HIV—and more people will die of AIDS.

Can those of us losing our jobs just give up? No. We must—like Joe and Gregg and Sean and Jack—do community care. We must practice community education and harm reduction. We must care for each other in the face of state neglect.

And yet, Sonnabend had a job; so did Fauci (for decades). Today, tens of thousands (at least) of people who did HIV/AIDS work are out of jobs globally. And probably hundreds of thousands of health workers in the US and around the world are also out of jobs. Public health needs public support from the state, full stop. Sonnabend and ACT UP pushed and prodded and and forced the NIH and NIAID and the CDC and FDA—but they also needed them. Now, each of those agencies has had devastating cuts, with their ability to treat public health (and especially sexual public health) destroyed.

For instance, the lab that studied syphilis and tracks its mutations at the CDC has been shut down, its staff terminated; how can we prevent, treat and understand a mutating pathogen without a lab or any scientists?

We can’t.

How can we stop the better part of a million global AIDS deaths from growing if we are not getting drugs into bodies?

We can’t.

For me, the takeaway from Sonanbend’s memorial was this: After the Democrats dismantled the public health infrastructure built up for Covid-19 two years ago, and while the Republicans are ripping to shreds as much of the global public health infrastructure as they can, Sonnabend’s (and his collaborators’) model of community care is more important than ever. In a non-hierarchical way, doctors, patients, activists and—yes—even journalists must not only care about each other in radical ways. That will not be enough.

We must all also drop the pretense of detachment from politics. As ACT UP did decades ago, we must push on the levers of the state with everything we have, until it stops using money for war instead of care. As Trump wants a trillion dollars for the military, we must rally around ACT UP’s 1991 call to “Fight AIDS, not Arabs!” more than ever.

Instead of war, let fighting AIDS and syphilis and lead poisoning and pediatric cancer be our rallying call.

Steven W. Thrasher

Steven W. Thrasher, PhD, CPT, a journalist, social epidemiologist, and cultural critic, holds the Daniel Renberg chair at the Medill School of Journalism, and is on the faculty of Northwestern University’s Institute of Sexual and Gender Minority Health and Wellbeing. A former writer for the Village Voice, Scientific American and the Guardian, Thrasher is the author of the critically acclaimed book The Viral Underclass: The Human Toll When Inequality and Disease Collide. [Photo by C.S. Muncy]