Untangling the Wolf: Erica Berry on Fairytales, Fear, and Dismantling Narratives

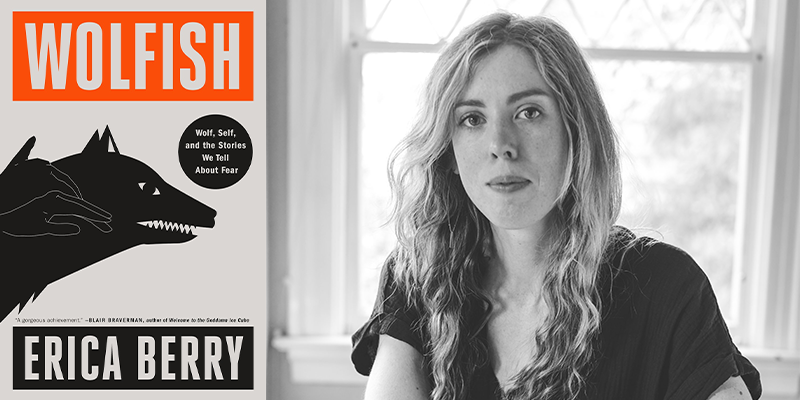

Martha Anne Toll Talks to the Author of Wolfish

I met Erica Berry at the Monson Arts Residency in 2019. From the outset, it was clear Berry was not only a kind, loving person, but also a person of great thought-fullness. I have enjoyed reading her work ever since and was thrilled to hear her debut book was on the way.

Wolfish: Wolf, Self, and the Stories We Tell About Fear is a collection of essays that coheres into a complex, interwoven narrative of Berry’s journey into her own fear, her passion for the environment, the threatening and destructive mythology around wolves; the fraught ecological efforts to save the wolf from extinction; and Berry’s love of reading and writing. In sending a deep probe into her psyche, Berry has managed to strike a balance between herself and others, showing herself to be a literary empath.

Berry’s capacious intellect shines; she has threaded in a library’s worth of meaningful references to other writers’ efforts around a constellation of related subjects. Readers are sure to find themselves reflected in these pages and will respond to the tough questions Berry poses.

I caught up with Erica Berry by email.

*

Martha Anne Toll: How did you get interested in wolves?

Erica Berry: I had always been interested, but while I was in college, one Oregon wolf, OR-7 left his pack in the eastern part of my home state and wandered into the western part—where no wolves lived—looking for a mate. He broke records: first wolf across the Cascades, then first wolf into California. (A government-sponsored extermination program drove the species to extinction mid-20th century, and only after wolves were reintroduced to Yellowstone and Idaho in the mid-1990s did their descendants start dispersing.) Social media accounts emerged to follow and ventriloquize OR-7, a nonprofit held a competition to name him, and there were headlines abroad about his “search for love.”

The popular Western binary of wolf as either villain or idolized role model troubled me. I became interested in why we talked about wolves this way as well as the broader cultural ramifications. There’s a huge tradition in popular culture of people being compared to wolves, but those conflations struck me as unfair to both two-and four-legged animals. I wanted to untangle the biological wolf from our wolf metaphors.

When I wrote my college Environmental Studies thesis about wolves, my mother was hospitalized with a mysterious illness later traced to a tick. Somebody mentioned offhandedly that ticks were a growing problem because there weren’t enough predators to limit rodent and deer populations. This was a revelation, like some weird Little Red Riding Hood in reverse: I was worried about my mother because she had been bitten in the woods. I started thinking about wolves’ burgeoning populations not just for aesthetic reasons but for their ecological role.

The popular Western binary of wolf as either villain or idolized role model troubled me.MAT: Can you discuss the various meanings of Wolfish and how you came to think about these complexities?

EB: I had another working title, Cry Wolf. When we had to rename the book (long story…), I wanted something short and punchy that could be interpreted in different ways. There are many smart wolf books already out there; I wanted to signal that mine was not just about real wolves but also about our projections of them, the stories we tell.

My mom thought of the new title—she’s one of my best thought-partners, and I owe her. Wolfish means, “suggestive of a wolf.” I liked that human projection and metaphor was tied into the definition. We are the ones who look at the hungry kid eating and say they have “a wolfish appetite” though we don’t know what that means. My sister though “wolfish” sounded like someone giving a sloppy kiss.

Maybe that’s my book: a whole smooching smash of emotions and research, intimate but also a little overwhelming. I like the allusions of gluttony, voraciousness, no restraint, of too much. In Western fairy tale culture, wolves are often gendered male. When I’d heard “wolfish” in the past, I I’d associated it with men. The prospect of slapping that title onto a book that’s vehemently first-person, rooted in my own embodied life as a woman? It just fit. My editor Nadxi Nieto sent me an email about shouting it toward someone in a bar—that’s the dream. I want people to do a little eyebrow-raise when they hear it: Am I hearing this right?

MAT: Why do wolves figure so prominently in fairy tales?

EB: Why wasn’t it ever “the big bad bear?” Wolves live in many ecosystems across the northern hemisphere, they’re adaptive, and even though they avoid humans, their howls create sonic bread-crumbs, becoming larger than life. Fairy tales emerged amidst a real-life legacy of European leaders vilifying wolves—conjuring them as a threat to livestock and women—to build unification, rallying troops against an easy enemy to distract from, say, immense financial inequities of life. Fear is a powerful tool for the ruling class. The wolf became scapegoat.

Part of our fascination with wolves goes back to similarities: we both tend to live communally, sometimes mating for life, helping to raise one another’s young. We often want to eat the same things. Also, and this is darker, the biggest threat to another wolf, or another human, is another member of its own species. I went to my own experience: the adolescent girl drama. The more we shared, the more we felt our own territory was threatened. Can I extrapolate high school outward to wolf-human relationships?

MAT: Your book addresses fear in its many aspects. Do you think fear is different for women? How do crimes against women figure in your book?

EB: Fear is experienced differently across different bodies, always on intersectional lines. My former college thesis advisor, Anthony Walton, has a powerful essay with a scene about walking down the street as a Black man, feeling afraid while also knowing other people might be afraid of him. I became interested in internal narratives of speculative fear: the feeling so many of us who are not white men live with constantly, that any moment could crack into physical violence.

I was acutely aware that I—a white, cis-gendered, able-bodied, financially stable woman—was statistically living one of the safer lives in history. I was interested in the ways fear was an engine of narrative in my life. It didn’t matter that the fear didn’t come to bear: its anticipation took a huge toll. I wanted to unpack its mechanisms.

I wanted to untangle the biological wolf from our wolf metaphors.Just as we fall in love according to cultural scripts, so we fall into anxiety. I became interested in the way my victimhood felt predetermined. I wanted to write into how fear constricts my world; while also realizing that some amount was, maybe, keeping me safe. What lessons had I learned? Who taught me that fear, and who did it benefit, and—crucially—at what cost to others and myself did I bear it? I became as invested in peeling back the construction of the fairy-tale “girl” as the fairy-tale “wolf.”

The first iteration of my research, my undergraduate thesis, was only about real wolves. Then, a few weeks into graduate school, I was assaulted by a strange man on a dark street. I had a tiny keychain of pepper-spray in my bag at the time, but I felt totally unable to reach for it—my body completely frozen.

I kept thinking about Little Red Riding Hood—how uncomfortable I was with narratives around predator and prey, victim and villain. I was unsure how to own the emotion in my own body. I was frustrated by my body responses afterward—as if it was “irrational” to drive two blocks to a neighbor’s house in the dark—feeling resentful of white men running around like off-leash dogs at the dog park, while others of us stayed on our leashes with our heads down.

I wrote this book mostly during my 20s, when I was learning to live in my adult woman’s body in various spaces. That menace felt acute. To dismantle the stories about the “Big Bad Wolf,” I had to think about who that “wolf” was chasing. I wanted to interrogate not just the rusty metaphor but the scaffolding behind it. Not just how we grow out of fear, but how we grow into it. What should a parent tell a child about entering a scary world? What sort of “security” do I want?

MAT: How did you come to writing?

EB: In high school I thought of myself as a poet, capital “P.” A teacher talked about “chewy” sentences, and that’s what I liked: the lozenge-like quality of a perfect word. I was more drawn to Sylvia Plath’s diaries than to her poetry. Reading them was the first time I saw first-person nonfiction as witness and self-making, of metabolizing the world by bringing in other texts. I remember reading Toni Morrison’s Song of Solomon, one of my favorite novels, and realizing I was less interested in genre than in what unspooled on the page: vulnerability, intimacy, reconciliations with the big questions of love and death, and what it means to coexist with other bodies on this earth.

I chased those questions through various forms—poetry, short stories, half-attempted novels—before realizing that the first-person essayistic voice felt most compelling. I’m interested in the porousness between self and world. I like nonfiction that acknowledges the messiness of objectivity.

I have magpie-like sensibility, drawn to weird, shiny bits of life rather than to important dates or proper nouns; and to the syrupy void of big answer-less questions! I’m the tipsy person at the bar riffing on why a singer is in the cultural memory rather than trying to remember the year of their hit. (I’m fun! I promise.)

I’m interested in the porousness between self and world.MAT: What writers inspire you?

EB: Writers who inspire me are propelled by similar engines of interdisciplinary thinking, roving across genre and text borders, between self and world. In Robin Wall-Kimmerer’s Braiding Sweetgrass, we’re in the land of weaving; sit back and relish the mastery. Essayists like Rebecca Solnit, Eula Biss, Elissa Washuta, Claudia Rankine, Olivia Laing, Leslie Jamison, Jenny Odell, Kristen Radtke, Elisa Gabbert. At some point, I just holed up with a bunch of brilliant books that combined personal writing with research: Tressie Mcmillan Cottom’s Thick, Emma Eisenberg’s The Third Rainbow Girl, Lulu Miller’s Fish Don’t Exist, Cathy Park Hong’s Minor Feelings, Anne Boyer’s The Undying—I could go on.

I relish how Annie Dillard, Jamaica Kinkaid, and Gretel Ehrlich write about the natural world—also Amanda Thomson, whose book Belonging: Natural histories of place, identity, and home I picked up visiting the Canongate offices in London, it’s wonderful. I’m a sucker for a sentence! Whenever I can’t write, I pick up a book with crackling language or metaphors: Patricia Lockwood, Sarah Thankam Mathews, Ali Smith, Shirley Hazzard, Ocean Vuong, etc.

MAT: What books influenced your writing life?

EB: Annie Dillard’s The Writing Life, if only for the legendary advice to “spend it all, shoot it, play it, lose it, all, right away, every time. Do not hoard what seems good for a later place in the book or for another book; give it, give it all, give it now.” Melissa Febos’ Body Work was the pep talk I needed to stand behind the narrative “I.” For craft, I was captivated by Jane Allison’s Spiral, Meander, Explode. Until reading her craft analysis of different forms—the way a story can be circular or wave-like—I struggled to pinpoint how and why an author might pull off that structure.

Esther Kinsky’s novel River was literally and conceptually tidal. I’m often drawn to books with high-wire ideas but that also contain jarring, surprising sentences. Maria Tumarkin’s Axiomatic floored me in this way. Two books that influenced my sense of self as a human in the environment are Daisy Hildyard’s The Second Body, a book-length essay on how humans are a part of animal life, and J.R. McNeill’s Everything Under the Sun, which lives up to its subtitle as “an environmental history of the 20th century world.”

I kept thinking about Little Red Riding Hood—how uncomfortable I was with narratives around predator and prey, victim and villain. I was unsure how to own the emotion in my own body.MAT: In writing a book which is a deep exploration into your psyche, how do you find the right balance between yourself and others?

EB: I am neurotically insecure about the challenge. Like others who write through the lens of bodily experience, I had to silence that internalized patriarchal critic who says my experience is a distraction, self-absorption, etc. I am drawn to intimate first-person writing as a reader not because I’m trying to really understand the author, but because in poring over pages, I pour myself through them. Reading another writer who grapples with research—with how it refracts back on their life, reshapes their memory or perspective—gives me permission to confront myself. I want to invite others to grapple with preconceptions, not just around wolves, but other mythologies of place and self. I wanted to model that vulnerability on the page.

My truly brilliant agent, Marya Spence, reminded me that as I was trying to build authority and an argument in each chapter with research from other texts, archives, interviews, etc., I was allowed to use my embodied experience. It was revelatory to see the scenes of memoir and personal life in here as another form of evidence. If I’m trying to reckon with something, I’m going to consider all the clues on the table, including my experience. At the same time, my own life is inherently limited, so I never wanted the reader to get too comfortable thinking “Erica’s experience is generalized truth.”

MAT: What’s next for you?

EB: Part of what compelled this book was a very anxious period of my life. I was trying to figure out how other people lived beside specters of violence, uncertainty, mortality. Somewhere along the way, I defanged my brain. The world is still terrifying, but I feel more able to coexist with it. My next book involves a similar sort of kaleidoscopic and interdisciplinary focus, but instead of fear, I’m thinking about love. My writing practice is very self-serving in that way: I omnivorously chase down answers to the questions that are looming largest in my own life. It’s not that I’m writing for myself, but that I get bored if I already know how I feel about something. I’m circling questions about love and bodies and our planet’s environmental future and (once again) the stories we tell about all of that.

MAT: Anything else you want to add?

EB: The only thing I’d add is a word of appreciation for where you and I met, at Monson Artist Residency, and the value of places like that—havens of inquiry and curiosity between artists and writers —to allow projects like this one to seed. You and I have been in conversation about the themes in this book for years at this point: that’s inspiring for me.

___________________________

Wolfish by Erica Berry is available from Flatiron